Finally, an art museum tour for people who hate art

Nick Gray never gave much thought to museums until he was shown around New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art on a date. His companion apparently was an excellent tour guide.

Nick Gray never gave much thought to museums until he was shown around New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art on a date. His companion apparently was an excellent tour guide.

“After that, I fell in love with the museum and started to do these tours for my friends for free and for fun,” says Gray. Eventually, he turned his concept into a company.

Museum Hack offers three group tours most days at the Met. (Most cost $59. A “VIP night tour” option is available for $89.) It also conducts some at New York’s Museum of Natural History and plans to expand to the Brooklyn Museum before tackling its next American city (it hopes) early next year. The company promotes itself as a tour provider for people who don’t like museums. But Gray says he thinks the market is broader than that, including people who enjoy museums but want a new way of experiencing them. I’d put myself in the latter camp, and being a newcomer to New York who still had the Met on her to-do list, I decided to test out the service.

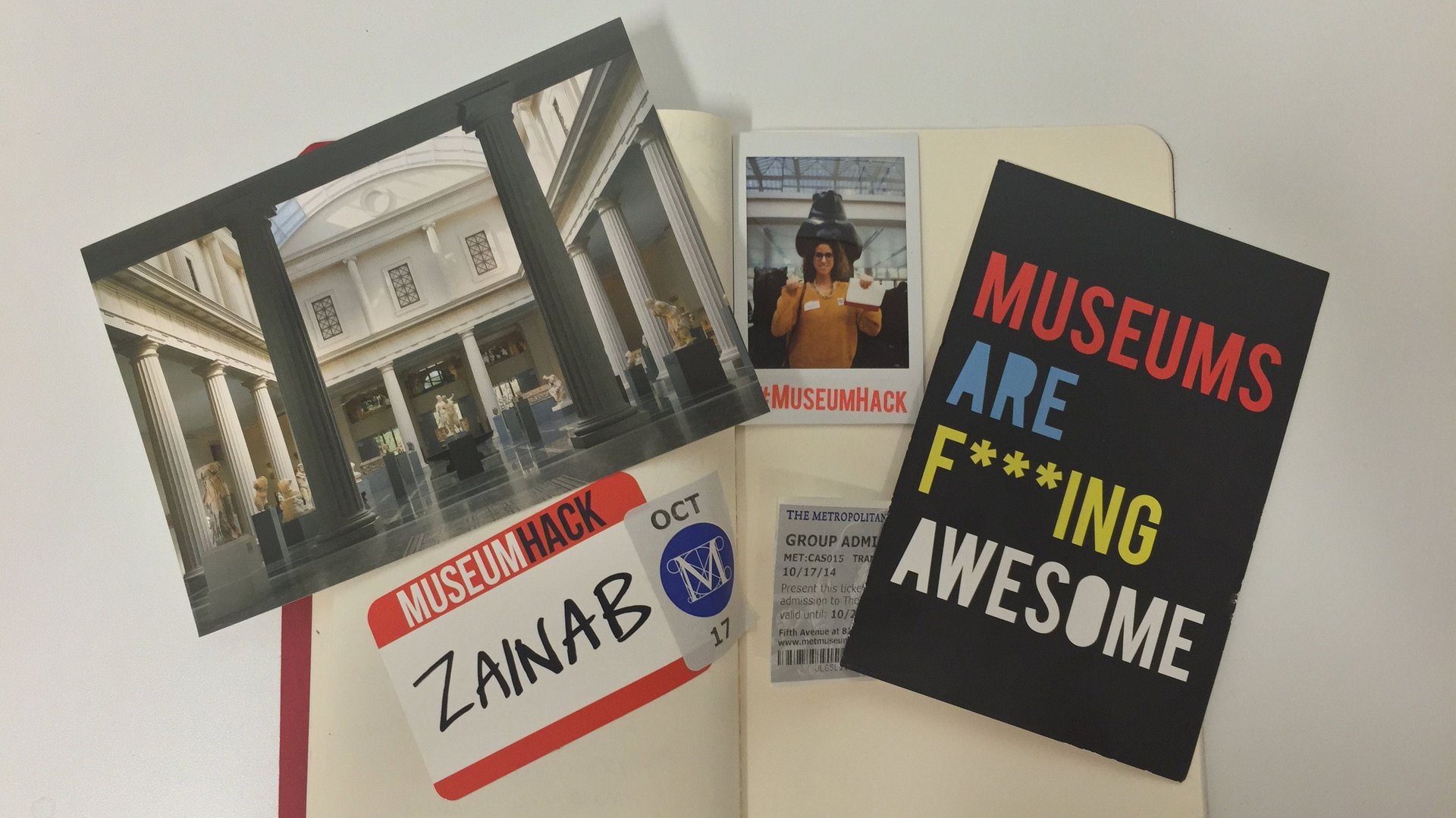

I had no problem finding my group amid the crowds of tourists in the Met’s lobby. (The museum sees more than 5 million visitors a year.) Other tour guides at museums hold up signs or umbrellas to keep themselves visible. I was able to pick out my Museum Hack tour guides from the message printed on their tote bags: “Museums are f***ing awesome.”

As our group assembled, the guides began asking where we were from. Some hailed from as far away as Denmark and New Zealand. While Gray says the tours were designed for people aged 18 to 39 (he thinks Millennials are particularly disconnected from traditional museum experiences) the company is attracting a broader age range than that. My tour group included a handful of older couples, and a few families with kids. All of them chose Museum Hack because they thought they would get something unusual out of the visit.

And they were right. Museum Hack’s “Un-Highlights Tour” of the Met was far different from the traditional museum tours I’ve been on. Here’s how.

The tour guides

When I asked Gray, along with both of my tour guides, whether they had extensive experience with museums, I received varying answers. Gray had never been involved in tourism or art history; he previously worked in the electronics business. He says he hires guides with diverse backgrounds; they might be museum educators, filmmakers, broadway actors, musicians—they just need to be effective storytellers.

One of my tour guides, Jessye Herrell, went to film school and graduated with a degree in visual arts and has always had an interest in art education. The other, Michelle Roginsky, has a background in film and theater. Roginsky describes the tour guide audition process as grueling; it consists of three or four rounds, one of which involves independently creating two hours of museum content to present.

Perhaps tour guides at other museums I’ve been to have had similarly interesting backgrounds. I don’t know; usually they don’t make it a point to tell you about themselves.

The content

While a regular museum tour might showcase five or six works of art, these tours squeeze in 10 to 12, making the sessions feel much more fast-paced. Each tour is different, based on interests of the guides and the group. Before our tour officially began, Herrell and Roginsky tried to gauge whether we were “Met virgins.” Halfway through the tour, they asked us to go around in a circle and say what we are passionate about. For one man, it was dental education, which prompted the guides to bring us to a walking stick that doubled as a flute and oboe, made out of narwhal teeth. Another woman said she loved animals, so the guides pointed out various animal paintings to her as we walked from piece to piece. The guides also will take requests for items, and work them into their routes. At one point during our tour, we voted on whether we wanted to see a major museum highlight or something more unusual—”badass” was the term the guides used.

The group voted for the latter, and as a result we got taken to a gallery with miniature portraits. There we heard the story of a notable miniature-portrait painter who painted a tiny portrait of her own breasts in an attempt to win over a man. (The effort was for naught.) While the breast portrait wasn’t on show at the museum, Herrell showed us the painting, along with many others, on her iPad. It was these “un-highlights” that seemed to have the most intriguing gossip or jokes behind them.

The presentation

Museum highlights were still covered on the tour, but the way they were presented is what made them stand out.

Instead of getting bogged down by the history of the Temple of Dendur, we heard about the role Jackie Kennedy played in the battle between the Smithsonian and the Met to get the temple. (A reward of her efforts: through the Met’s glass atrium, she had a view of the temple from her Fifth Avenue apartment.) And when looking at the famous painting Washington Crossing the Delaware, we mainly learned how inaccurate the painting really is.

The tour also was filled with museum fatigue-fighting exercises, like trying to guess the most expensive painting in a room (it was a Duccio worth $45 million). We snapped photos of ourselves with sculptures using the tour guides’ Polaroid camera, and picked out random people in different paintings and came up with our own back story for them (with prizes for the most creative). “You don’t realize it, but you’re getting to know art that way by making observations and looking into the context,” says Herrell. “It’s all about making it a conversation rather than a lecture.” As someone who isn’t an art history buff, I especially appreciated this.

Gray says Museum Hack’s biggest competition isn’t other museums that offer their own tours, but rather other tourist attractions like Central Park and broadway shows, which are more natural destinations for people who tend to shy away from museum visits.

In Gray’s line of work, keeping the tours filled is one gauge of success. But so is teaching people how to like museums, and encouraging them to visit more, he says. “We got so much out of the lifelong learning you can do at museums,” says Gray. “It’s a weird, nontraditional goal of the business, but we want people to feel the same way.”