It pays for companies to do the right thing. Even Adam Smith would agree

Winston Churchill liked to quip that you can always count on Americans to do the right thing—once they have exhausted every other alternative. That joking comment bites a little too deeply these days, as corporate America continues to dig out of the wreckage of bad decisions, ethical lapses, exaggerations, and even outright fraud of the boom years that ended so abruptly.

Winston Churchill liked to quip that you can always count on Americans to do the right thing—once they have exhausted every other alternative. That joking comment bites a little too deeply these days, as corporate America continues to dig out of the wreckage of bad decisions, ethical lapses, exaggerations, and even outright fraud of the boom years that ended so abruptly.

The good news? It’s more obvious now that doing the wrong thing doesn’t actually pay well in the long run. You can’t ultimately get away with it. Doing the right thing does pay. So when young managers ask me what is the most important thing they can do, I tell them to do the right thing: don’t cut corners, don’t hype and “juice” your performance. Focus on the things that create lasting value, rather than fleeting profit numbers.

I know this sounds fluffy to many hard-charging business types. I studied at the University of Chicago, the home of the late Milton Friedman, who was a passionate advocate that businesses have a sole responsibility to focus on financial returns, because their sole societal role is to create wealth.

Friedman made important contributions to the field of economics. But this theory has turned out to be neither correct nor healthy. It has not worked for society, which continues to be beset by corruption, scandals, and breaches of trust, and it has not worked for a number of companies and their shareholders.

In fact, the intellectual father of capitalism, 18th-century Scottish thinker Adam Smith, is too well remembered today for such phrases as the “invisible hand.” In truth, Smith’s legacy has been grossly oversimplified: he was a dogged advocate of the view that free enterprise absolutely required strong moral and ethical underpinnings, and that most market participants needed to be people of (to use his words) propriety, prudence, and benevolence in order for the system to work properly.

John Kay, who founded Oxford University’s new business school in 1996, calls this paradox “obliquity”: just as you can’t find happiness by looking for it, you can’t be profitable by relentlessly pursuing profits. Profits, like happiness, come to those who pursue other things first; for example, creating amazing products, elevating customer service, helping a colleague, or blazing a new trail.

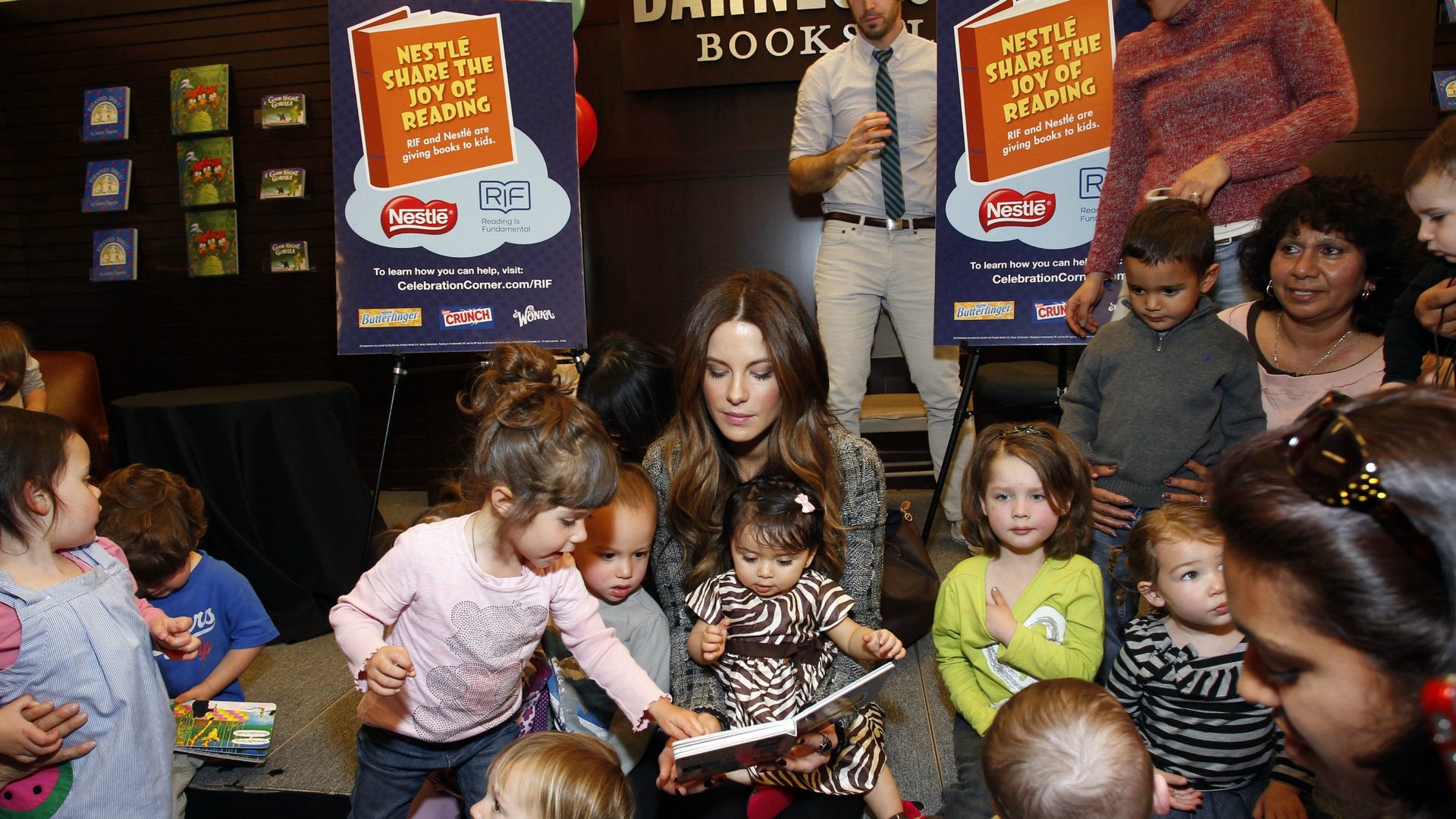

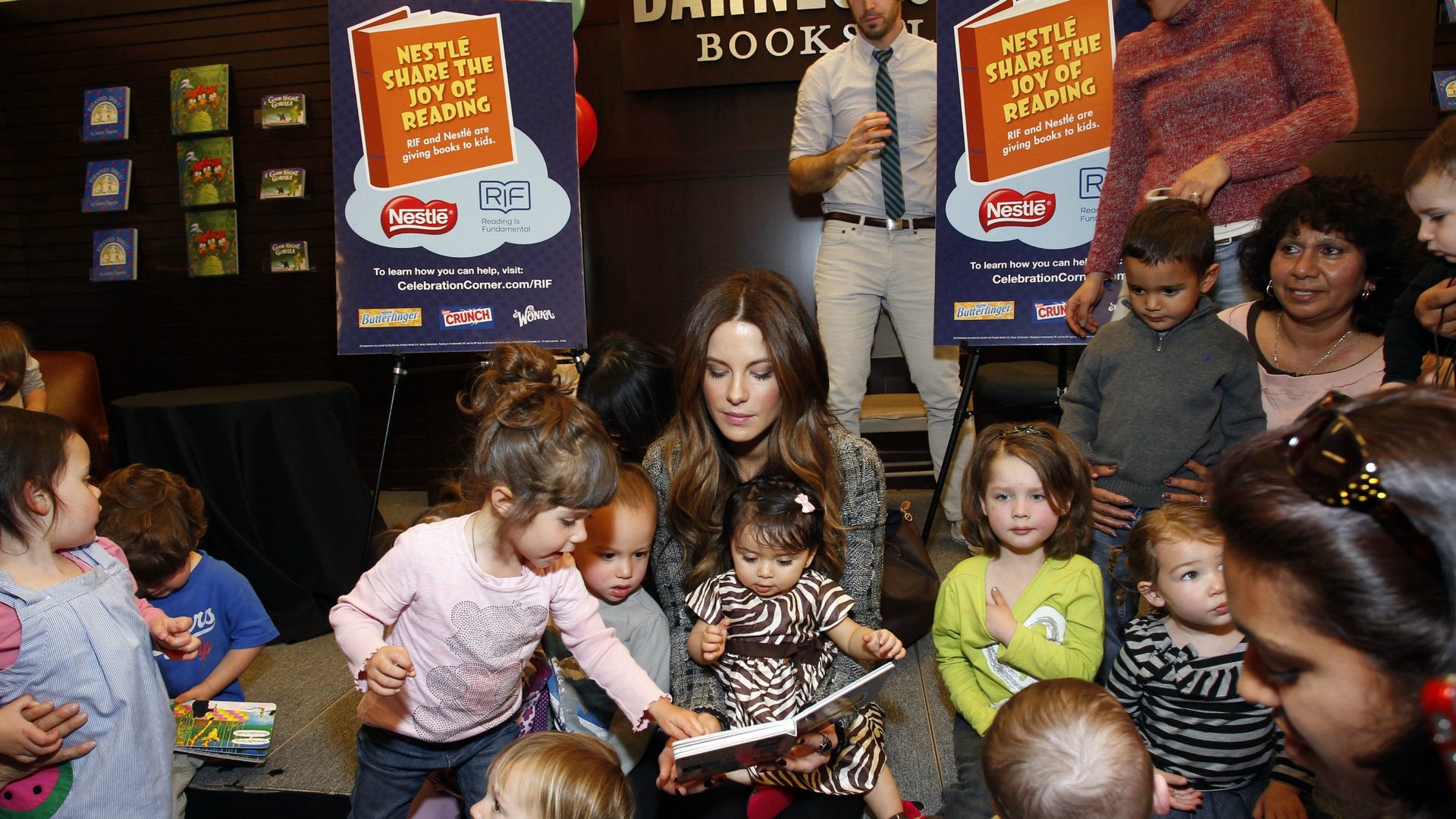

The world’s largest food company, Nestlé, calls it “shared value”: the many positive effects that radiate out from doing good commercial (not merely charitable) things that enrich consumers, citizens, farmers, suppliers, communities, countries—not just employees and shareholders.

Other examples? Coca-Cola, the world’s largest beverage company and most valuable brand, has committed itself to becoming water-neutral by 2020 along with a host of other such good citizen initiatives, demonstrating that the most successful companies can best fulfill their shareholder ambitions and society’s at the same time. Wal-Mart, the world’s largest retailer, has dramatically cut its carbon emissions while saving $200 million in costs, yielding enormous social and shareholder value. BASF, the world’s largest chemical producer, is yet another company at the top of its industry that equally finds the sweet spot where doing well and doing good converge—as intelligent materials reduce their weight and energy intensity dramatically while enhancing their functionality.

And for you cynics out there, yes, I take my own medicine. In 2006, I joined with more than 100 senior leaders of A.T. Kearney to buy our firm back from EDS in a management buyout. After a strong start, we charged headlong into a deep recession. It’s widely accepted that layoffs are standard operating procedure in tough times and many of our people expected it. Instead we sought to send a different message about this new post-MBO chapter of our firm’s 80-plus year legacy. We decided against any wholesale cut in our headcount. In my view, doing so would only boost our profits in the short-run at the expense of our competitive position over time. So we managed to hold our worldwide team of nearly 3,000 employees together and nursed the firm back to health. The strain on our bottom line was only temporary. High morale and robust growth have followed, allowing us to take back our place in the top tier of the consulting world.

All business leaders like to say they’re doing good. But unless that definition of success extends beyond bottom lines and shareholders they will never be producing true, lasting value.