A scrapped IPO offers a raw look at China’s rampant overfishing of tuna

China hauls in 12 times more fish than it admits to catching, according to a report by the EU parliament, and regularly exceeds international limits on fishing certain species. How can China be so casual about flouting its commitments? The drama surrounding a recent Hong Kong draft IPO filing (pdf)—and its hasty withdrawal—offers some clues, as flagged by the Guardian’s Shannon Service.

China hauls in 12 times more fish than it admits to catching, according to a report by the EU parliament, and regularly exceeds international limits on fishing certain species. How can China be so casual about flouting its commitments? The drama surrounding a recent Hong Kong draft IPO filing (pdf)—and its hasty withdrawal—offers some clues, as flagged by the Guardian’s Shannon Service.

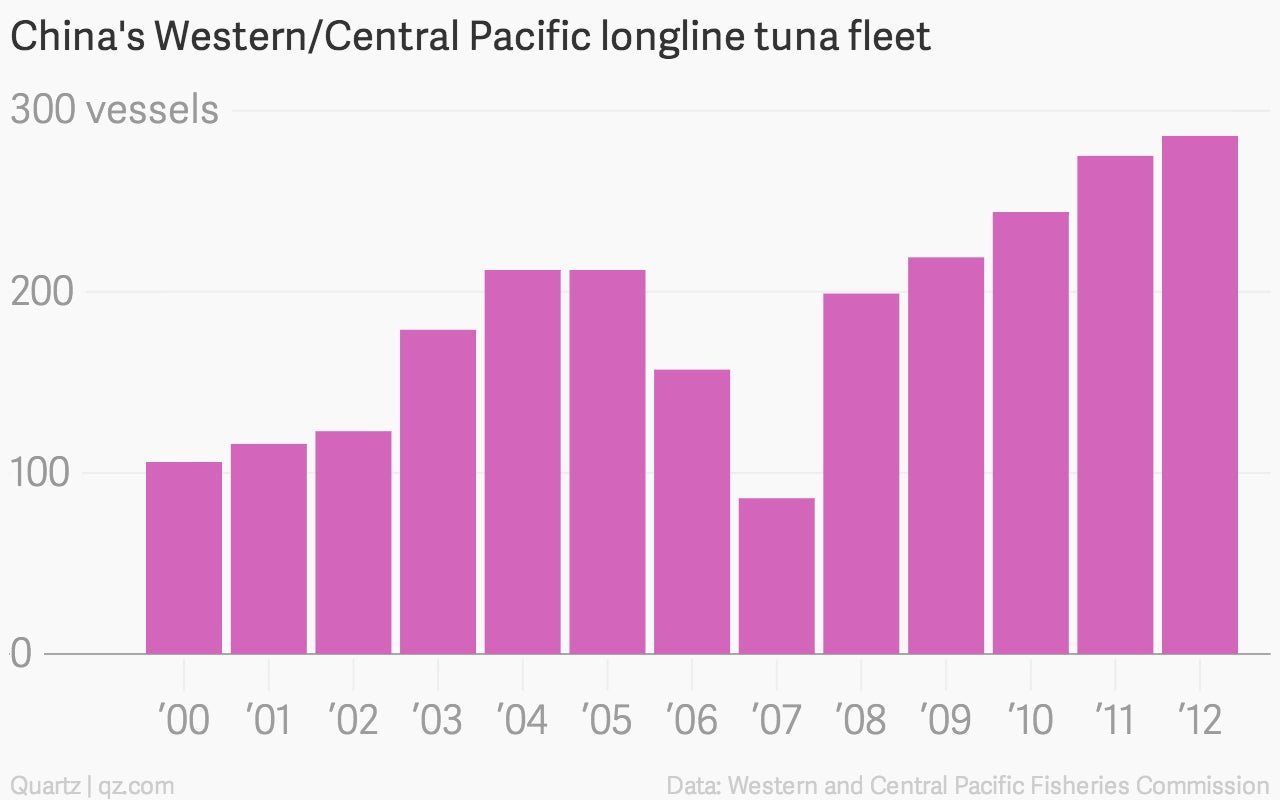

The company in question is China Tuna Industry Group, the biggest player in the Middle Kingdom’s huge tuna fleet. China Tuna, which currently has about $62 million in annual sales, was seeking to raise $100 million to expand its operations.

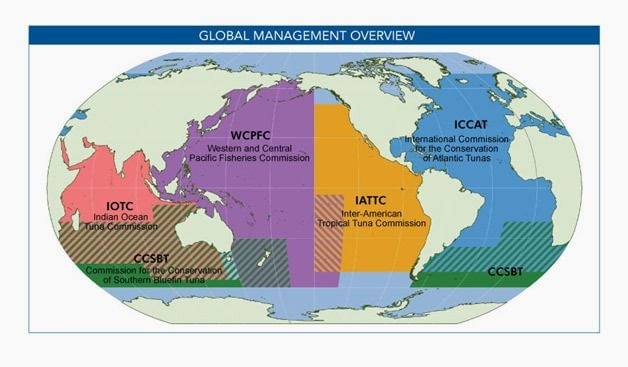

Tuna are strong beasties, able to zip across oceans with ease. Since no one country governs the waters where they swim, regional management bodies decide how many can be caught by each country without collapsing the population. Though any breach of those limits is considered illegal, it falls to each country to enforce these quotas.

And China, it seems, simply does not.

In fact, China Tuna’s prospectus says that Beijing has never contacted—let alone punished—Chinese fishing companies for their chronic illegal overfishing. It also claimed that international fishing limits apply only to China as a country, not to its fishing boats operating around the world, and that the regional organizations that oversee the limits have no power to sanction violators.

That’s why, says China Tuna’s draft prospectus, it plans to carry on in the Pacific and Atlantic in “substantially the same manner as we presently operate”—i.e. without concern for catch limits.

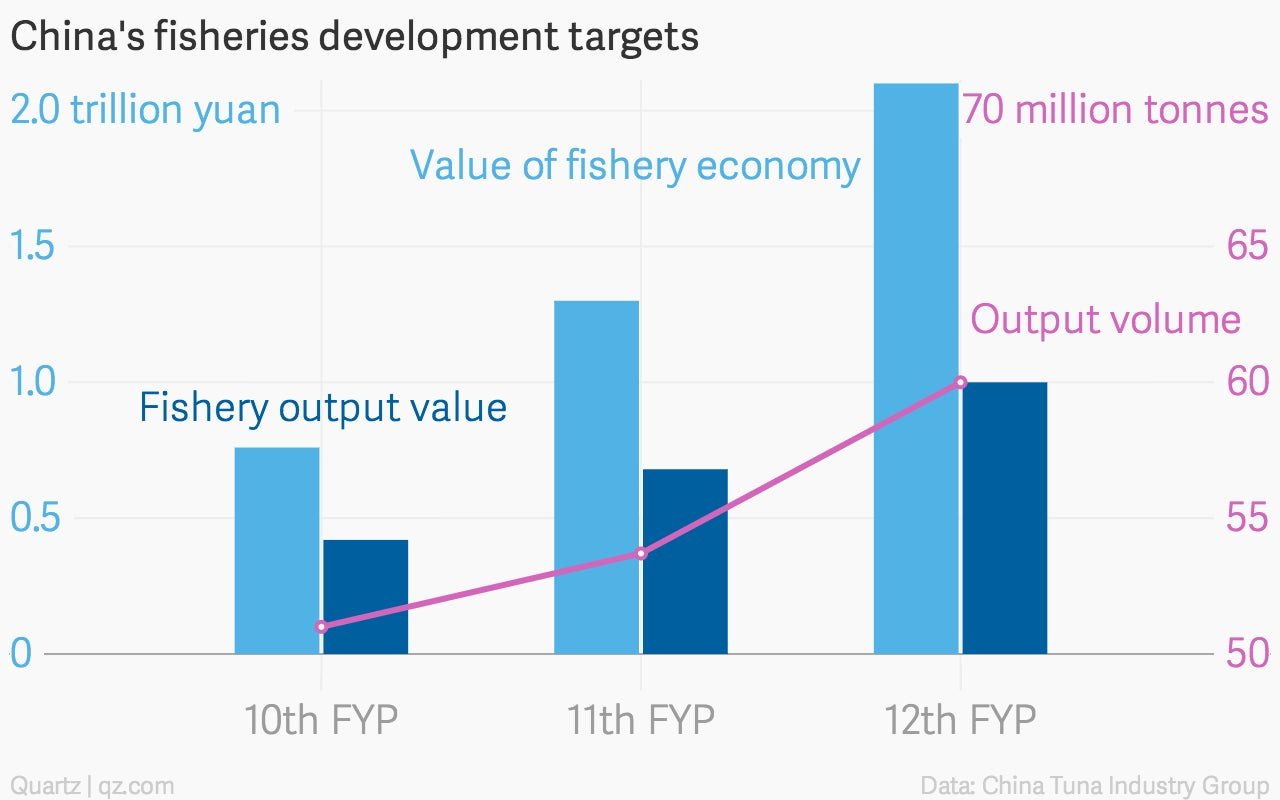

It’s not like the Chinese authorities have been oblivious to China Tuna’s activities. Not only has it given China Tuna tax and tariff breaks, according to the IPO draft, it has bestowed government grants and, though a state-backed university, cooperated with the company on researching tuna stocks. This is in keeping with the government’s strategic support of high-seas fishing.

Still, the stark revelations from China Tuna’s IPO filing didn’t sit well with Beijing. After Greenpeace condemned the company for overstating the bigeye tuna population, the government ordered the group to withdraw its listing—which it did—and to publicly correct the filing’s “untruthful content” (link in Chinese). Any further repercussions, said the government, will depend on the company’s compliance.

China Tuna is clearly not solely responsible for China’s illegal tuna overfishing. But it’s a major player; its prospectus boasts 22% of China’s longline premium tuna market.

While most other countries’ vessels are catching fewer and fewer bigeye tuna—thanks both to shrinking quotas and diminishing supply—China Tuna’s landings are rising. Despite the fact that, from 2011 to 2013, China’s Pacific bigeye catch limits were slashed 8%, the company’s catch sales grew by 60%, estimates China Dialogue, eventually hitting 7,000 tonnes (7,720 tons). That compares with the 13,200 tonnes of Pacific bigeye allotted to China’s entire fleet (Pacific bigeye constitute the majority of China Tuna’s sales).

Even as China Tuna’s promised investors it will continue to ignore catch limits, the filing explains why catch limits are important—namely, to make sure fishermen leave behind just enough fish in the sea to replenish their populations. And since quotas are generally calculated on the assumption that everyone will stick to their limits, there’s not a lot of room for miscalculation.

In fairness to China, many smaller countries exceed quotas and underreport catch volume too. But when the biggest fishing nation on the planet shirks its quota commitments, it’s pushing fishing stocks a lot closer to collapse.