How to create more silence in your life

On a hot August night in 1952, a pianist in Woodstock, New York, created an uproar in the world of music by sitting down for four minutes and 33 seconds and playing nothing at all.

On a hot August night in 1952, a pianist in Woodstock, New York, created an uproar in the world of music by sitting down for four minutes and 33 seconds and playing nothing at all.

The audience stirred and murmured as he quietly opened and closed the keyboard lid, marking the beginning and end of each movement. Some people rose and left. For four tense minutes, the only “music” was the confused rustle of concertgoers, moving to no particular beat, orchestrated by everyone and no one. The piece was called 4’33.”

“There is always something to see, something to hear,” the composer, John Cage, would write later about his inspiration for that piece. It was fitting that 4’33” was performed just four years after the publication of the famous information theory, in 1948, that would lead to binary code, and eventually to the booping, beeping, ringing aural overload in which we now live.

Humans have always tried to make sound, but there has never been a need to create quiet like there is today. In 2007, an artist named Jonathon Keats made a ringtone version of 4’33” cleverly called “My Cage (Silence for Cellphone).” In a video released through the artist’s YouTube channel, it is described as a “silent ringtone that brings quiet to the lives of millions of cellphone users as well as those close to them.” In 2011, an artist created a jukebox that contained only unique recordings of nothingness, calling it the world’s quietest jukebox.

In fact, since Cage’s work debuted in 1952, there have been at least 50 musical scores consisting of variations on silence. Before Cage, the number on record was about five.

“While it’s true the musician or musicians performing the work never play a note, Cage’s interest was in embracing what is happening beyond the stage,” says David Platzker, the MoMA curator who oversaw a Cage exhibit earlier this year.

“Incidental sounds, random sounds, mechanical sounds, and other noises generated by chance operation become the musical work,” he says. “Thus every presentation becomes temporal, unique, and engrossing to those who engage with it.”

The ever-present rhythms of life that Cage sought to expose with 4’33” have become a raucous symphony in the 62 years since the piece was introduced. Noise as a public health issue was first acknowledged with the emission standards set with Congress’s passing of the Noise Control Act of 1972, addressing the volume caused by machinery, construction, and motor vehicles. Since then, we’ve become acquainted with thousands of unique new sounds produced by the personal appliances, electronics, and devices that have found a place in our lives. While we’ve grown to live within this ocean of noise, which tells us how to function, it’s another form of information for us to catalog and analyze.

Today, silence is such a rare commodity that it is often considered a luxury. The headphones of the moment come with active noise cancellation effects as standard on high-end models, some of which cost over $400.

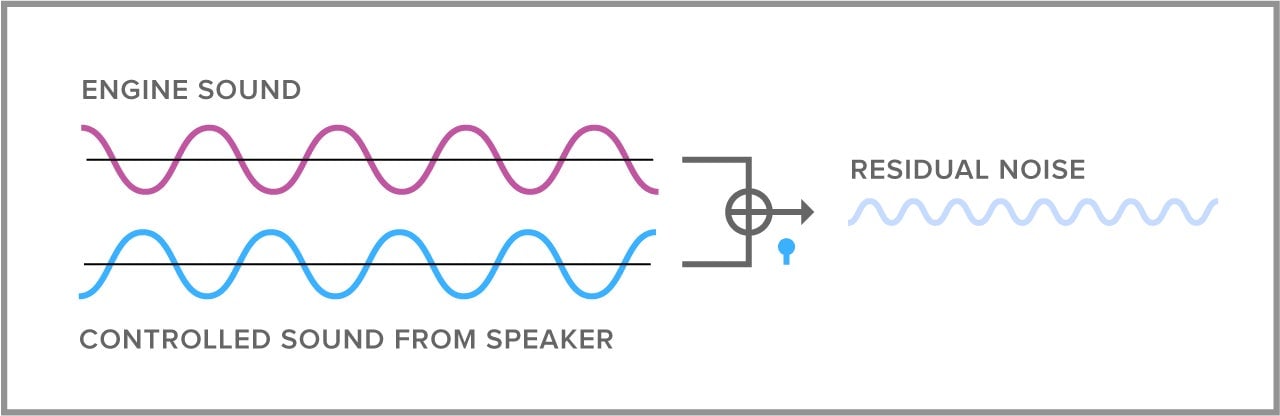

Noise cancellation works by a principle called “subtraction by addition.” Tiny microphones embedded in the overhead console of the Lincoln MKC, for example, monitor engine noise in the cabin, then emit opposing acoustic waves sent through the speakers. When the opposing wave meets the original sound wave, the result is silence.

Or, at least, it’s “digital silence.” The system creates a tailored sound experience, enhancing the cabin ambiance and helping to refine engine sound. In Sport mode, a setting within the available Lincoln Drive Control feature, the system further enhances certain sounds to align with the overall driving experience.

Anechoic chambers, or sound-deadening rooms, “can be musical tools, as white paint can be a tool,” says Platzker. “But neither are ends in themselves.”

In a 1957 lecture, John Cage said man-made sounds shouldn’t be an attempt to bring order out of chaos, or to create an artificial experience in a bubble. Instead, he saw it as a backdrop for the rest of life, “simply a way of waking up to the very life we’re living.”

This article was produced on behalf of Lincoln by the Quartz marketing team and not by the Quartz editorial staff.