Finally, the US admits it: AP classes are way too white

This post has been corrected.

This post has been corrected.

A US federal government release last month had a disorientingly retro ring to it: ”Black students to be afforded equal access to advanced, higher-level learning opportunities,” the Department of Education proclaimed—six decades after the country’s Supreme Court determined that segregation in public schools was unconstitutional in the landmark ruling known as Brown vs. Board of Education.

The acknowledgement by the US government that segregation is alive and well in American public schools came in the announcement of an agreement with a New Jersey school district over the controversial practice known as “tracking”—designating students for separate educational paths based on their academic performance as teens or younger.

The DoE and advocates have said tracking perpetuates a modern system of segregation that favors white students and keeps students of color, many of them black, from long-term equal achievement. Now the Department of Education’s Office for Civil Rights is trying to change the system, one school district at a time.

Proponents of tracking and of ability-grouping (a milder version that separates students within the same classroom based on ability) say that the practices allow students to learn at their own levels and prevent a difficult situation for teachers: large classes where children with a wide range of different needs and skill levels are mixed together. In many districts, the higher-level instruction in “gifted and talented” or advanced placement (AP) classes is what keeps wealthier families from entirely abandoning the public school system.

But opponents say the ill effects for the students in the lower-skilled classes negate the advantages that the students in the advanced classes gain. Many education researchers have argued that tracking perpetuates class inequality, and is partially to blame for the stubborn achievement gap in the US educational system—between white and Asian students on one side, and black and Latino students on the other.

Race is the issue, not just class

One New Jersey parent, Walter Fields, describes watching the effect of tracking first hand with his own African-American daughter, when she was denied entry to an advanced freshman math class. She had the middle school grades and standardized test scores to take the higher-level math class, Fields says, but she didn’t get the required recommendation from a teacher to take the class.

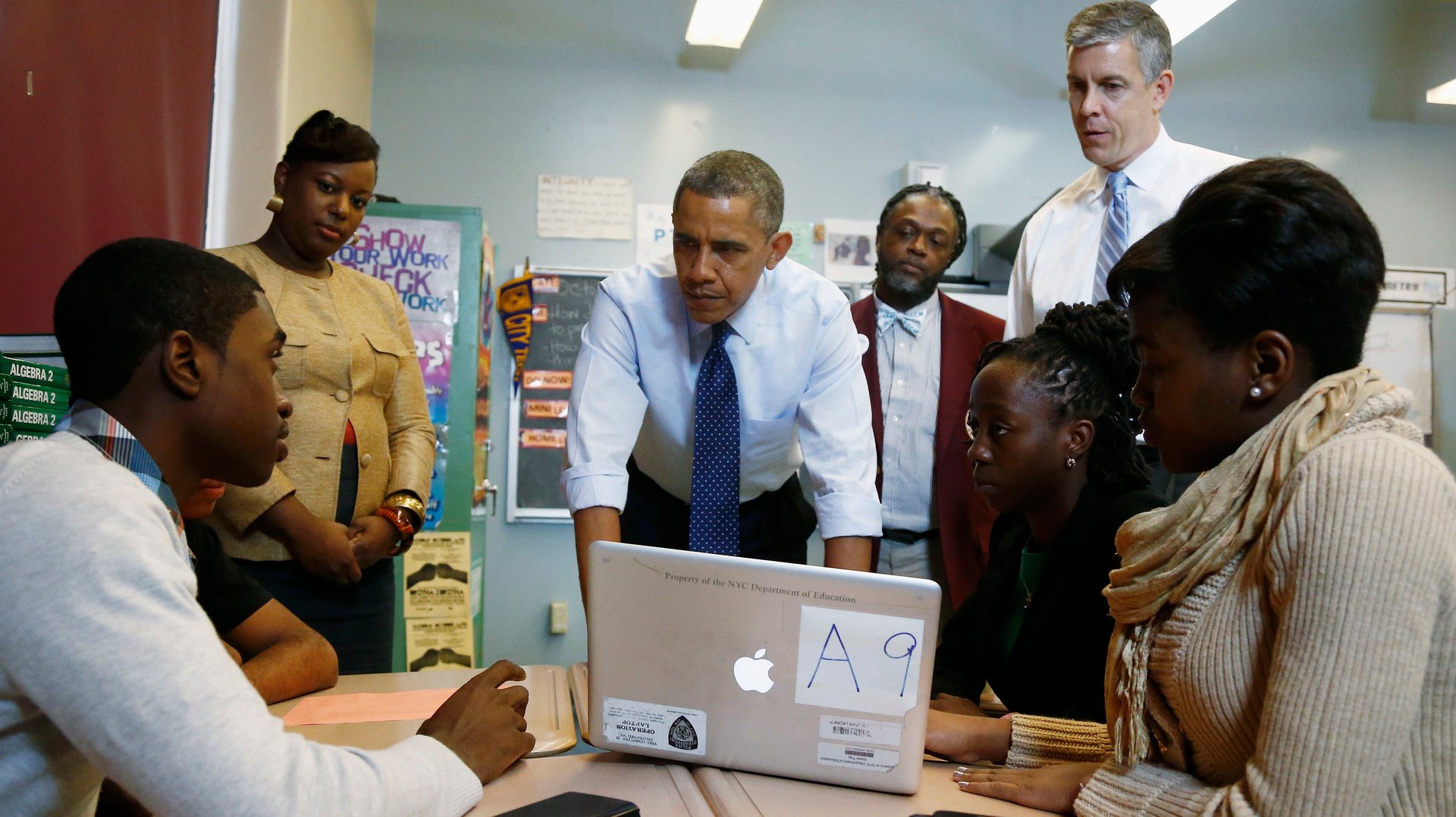

That didn’t change until Fields and his wife petitioned the principal to allow their daughter to take the higher-level class. Fields is part of a complaint that the American Civil Liberties Union and the The Civil Rights Project at UCLA filed against the South Orange Maplewood School District, alleging that tracking unfairly holds back African-American and Latino students.

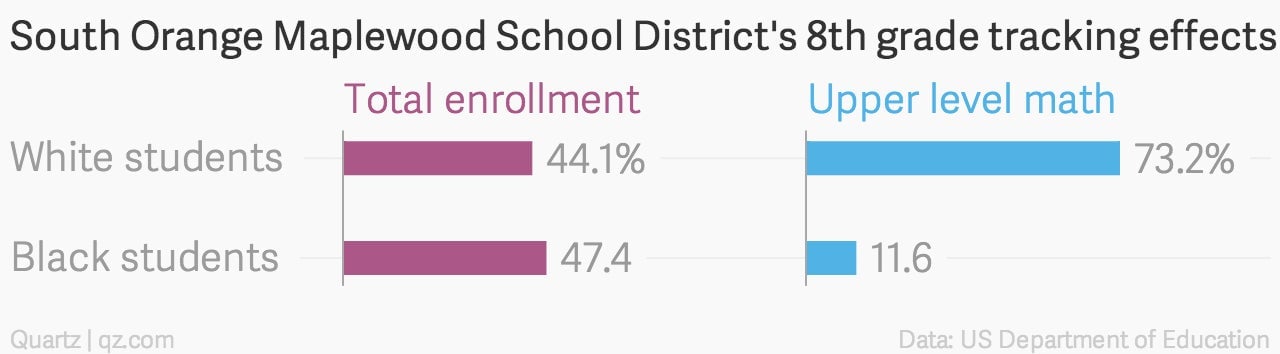

“Now we arrive at the point—in 2014—where you can literally walk down a hallway in Columbia High School and look in a classroom and know whether it’s an upper-level class or a lower-level class based on the racial composition of the classroom,” Fields tells Quartz.

Fields, the editor of the website North Star News, says that tracking is a racial issue, not just one of class—there are plenty of middle-class black students, like his own daughter, who find themselves tracked into lower level classes.

South Orange Maplewood does have a racial disparity issue in its upper-level classes, its board of education president, Beth Daugherty, acknowledged in an interview with Quartz. The diverse district, within commutable distance to New York City, has a well-educated and upper-middle-class population, including professors, lawyers, and journalists, she says, but about a fourth of the high school also receives free and reduced lunch, pointing to its socioeconomic diversity.

The district had 6,622 students—38% of them black and 49% white—as of June 2013. But at every level where students are tracked, black students are underrepresented in higher-level classes, from fourth grade through high school.

The district entered a resolution agreement (separate from the ACLU complaint) with the Department of Education last month, the one referenced above, which requires it to hire a consultant to examine the practices that led to the racial disparity, and to come up with a plan to increase equity.

No easy fixes

“We know how to go after this problem,” says Catherine Lhamon, the US Department of Education’s assistant secretary for civil rights. “It’s bad news that the problem persists.”

With tracking deeply established in schools across the country, eliminating it entirely is easier said than done. Every school district has different demographics, infrastructure and problems. So the DoE’s approach is a painstaking one.

The US secretary of education, Arne Duncan, wrote a letter (pdf) to the country’s school districts last month reminding them of Brown vs. Board of Education, and calling to their attention the “disparities that persist in access to educational resources.”

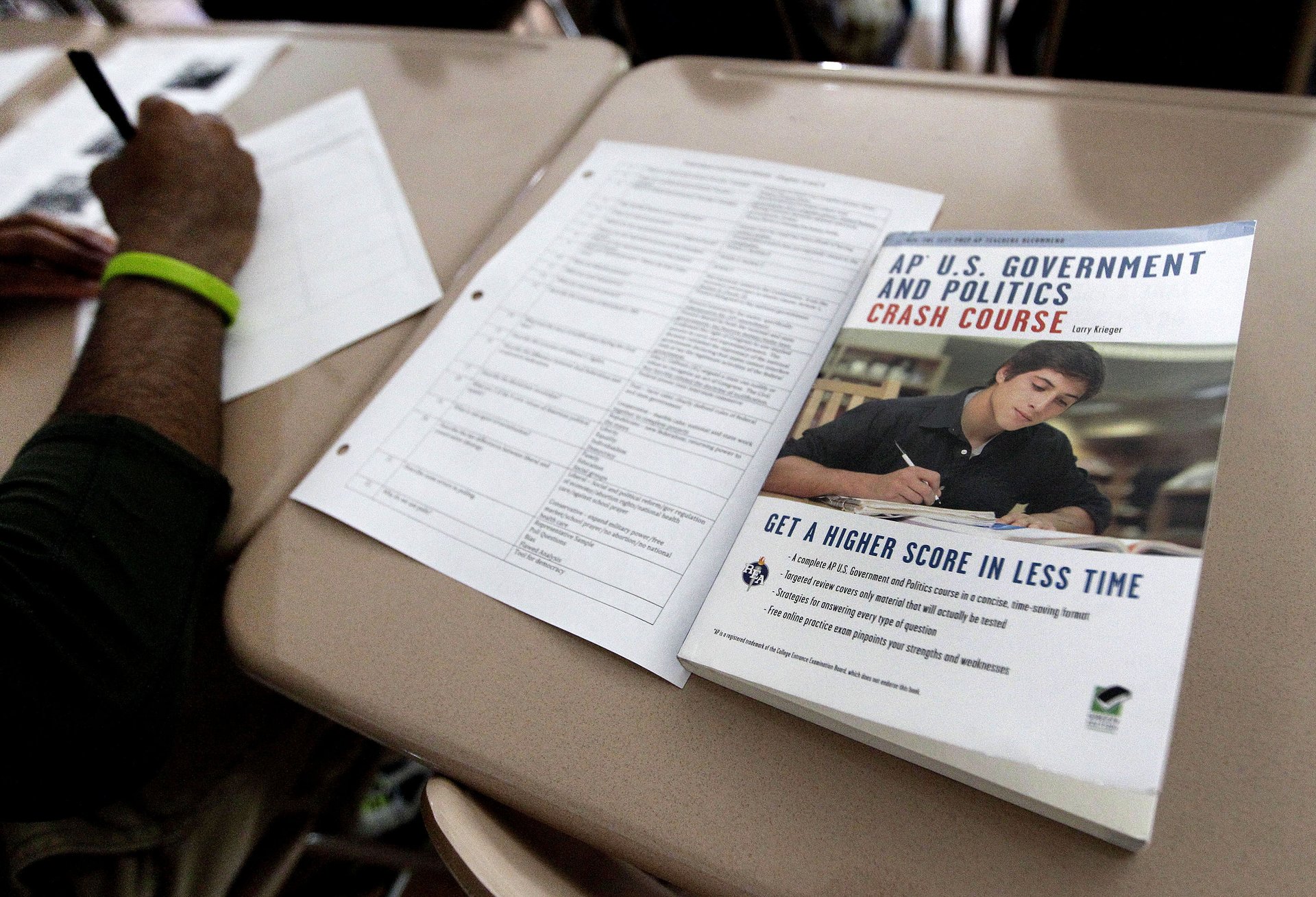

Duncan acknowledged the value of accelerated, subject-specific, and “gifted and talented” programs for students who show particular promise or preferences. ”But,” he writes, “schools serving more students of color are less likely to offer advanced courses and gifted and talented programs than schools serving mostly white populations, and students of color are less likely than their white peers to be enrolled in those courses and programs within schools that have those offerings.”

In the 2011 to 2012 school year, for example, black and Latino students represented 16 percent and 21 percent, respectively, of high school enrollment nationwide, the DoE says; but they were only 8 percent and 12 percent of the students taking the advanced-level math class calculus.

Duncan also warned the districts that his agency is conducting investigations and compliance reviews to ensure that their tracking policies are not segregating students in violation of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 (Title VI), which prohibits discrimination on the basis of race, color, or national origin within federally funded programs.

How tracking came to be

Tracking has been around since the beginning of the 20th century, when schoolchildren were put on different tracks after a certain age, often based on class—vocational for those from working class backgrounds, and general education for wealthier students, Christina Theokas, director of research for the advocacy group Education Trust, tells Quartz.

After the Brown v. Board of Education ruling in 1954 that mandated the desegregation of US public schools, the system became essentially a form of resegregation (pdf, page. 4). Those with money and resources could game the system to ensure that their kids tested into the higher-level classes, and poorer children, many of them black, were left behind in the lower-level classes.

In other countries, such as Germany (where the practice is widespread and not particularly controversial), tracking starts young and separates students onto different paths varying from general education to vocational. The system has been shown to increase the achievement gap, says Stanford researcher Eric Hanushek.

He researched educational systems (pdf) that do and don’t track, and found that eight out of the nine countries in his study that track students before the age of 16 see that the difference between highest and lowest test scores is significantly larger than the range in countries that don’t track. (He did not count the US, because it does not have a nationwide policy and tracking is most common in high school.)

The 1980s and 1990’s brought an influx of research in the US suggesting that while students in the upper level, college-focused classes may be served well by the separation, the students in the lower classes were suffering disproportionately—not only did they start behind, but the difference in instruction ensured that they had little opportunity to catch up.

The No Child Left Behind Act of 2001 required schools to focus on struggling students and raise proficiency test scores, which prompted many schools to separate out children who were behind, to provided targeted instruction. This led to an increase in ability grouping in lower grades, Theokas said.

It’s a fact of urban life that parents with means will go to great lengths to get their children into the best possible programs, says Joyce Szuflita, who is a consultant for New York City parents trying to navigate the educational system. New York practices an extreme form of tracking, with students able to test into special “gifted and talented” schools at as young as 4.

Szuflita says that not all the parents who hire her as a consultant want their child in a special school, but speaking generally, she tells Quartz, “all parents think their kids are brilliant.”

A piecemeal approach to change

The US federal government’s push to turn the tide of classroom inequality has intensified in the last three fiscal years. In that period, the Department of Education’s Office for Civil Rights has resolved cases with 16 districts, all racially diverse and ranging from 7,000 to upwards of 60,000 students. The Office for Civil Rights currently has 40 similar cases under investigation, according to a spokesman.

In those districts, the agency has identified unequal racial representation in gifted and talented programs, advanced placement courses or other upper-level classes. The probes often result in agreements that give the districts a few months to review the policies and practices in schools and identify inequality in college preparatory and upper level courses, and then less than a year to suggest steps to rectify them. The federal department must approve the process, as well as the measures the school plans to take.

Theokas says that this individualized process makes sense, rather than prescribing the same fixes across the board. “Understanding the problem is the right first step,” says Theokas. “I think that they [the DoE] have a bully pulpit, and that they should use it to highlight the … opportunity gap problem.”

But districts can’t stop at creating a plan, said Phillip Lovell, vice president for policy and advocacy at the group Alliance for Excellent Education. “The key thing is there is oversight, so knowing that there are timelines and consequences,” Lovell tells Quartz. “That that plan will actually be implemented.”

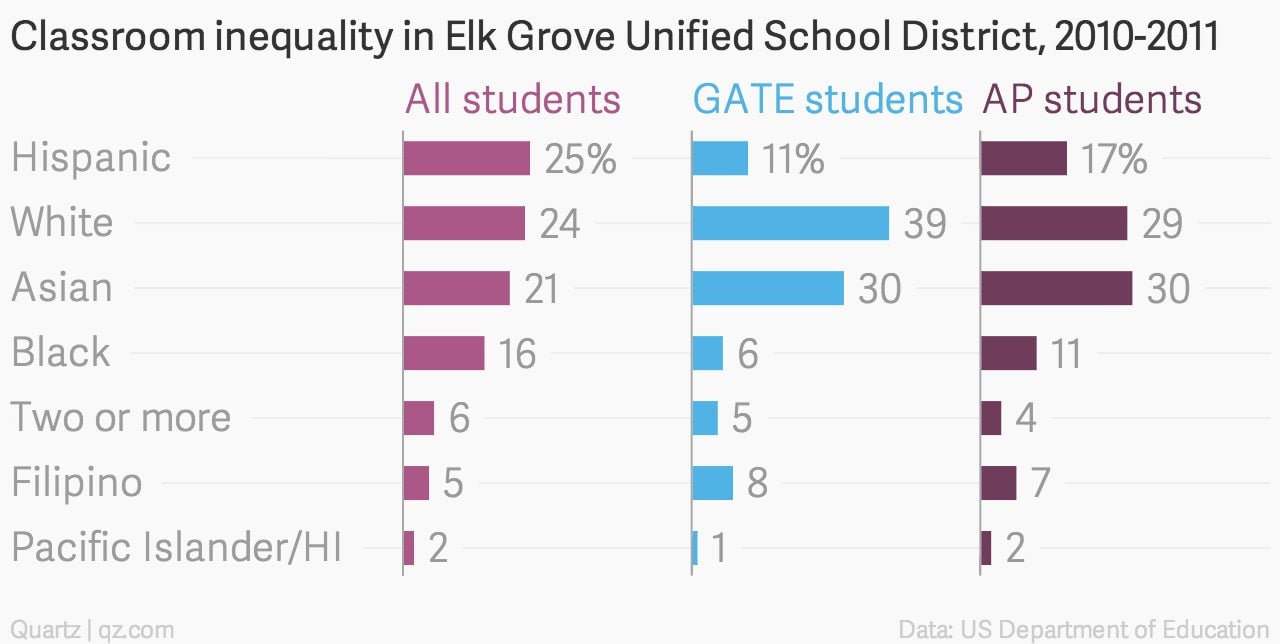

Duncan’s agency isn’t trying to uniformly prohibit all tracking. For example, a July resolution with California’s Elk Grove Unified School District (pdf) doesn’t shut down its gifted and talented education (GATE) program, but requires the district to make sure the program includes a representative sample of black students, who made up 16% of the district but just 6% of GATE.

What’s next?

The New Jersey school district, South Orange Maplewood, has been trying to correct its segregation problems, removing tracking from almost all classes in elementary through middle school—math remains separated in eighth grade—and looking into whether to reduce the rigid requirements that are currently in place for a student to move into a higher level class.

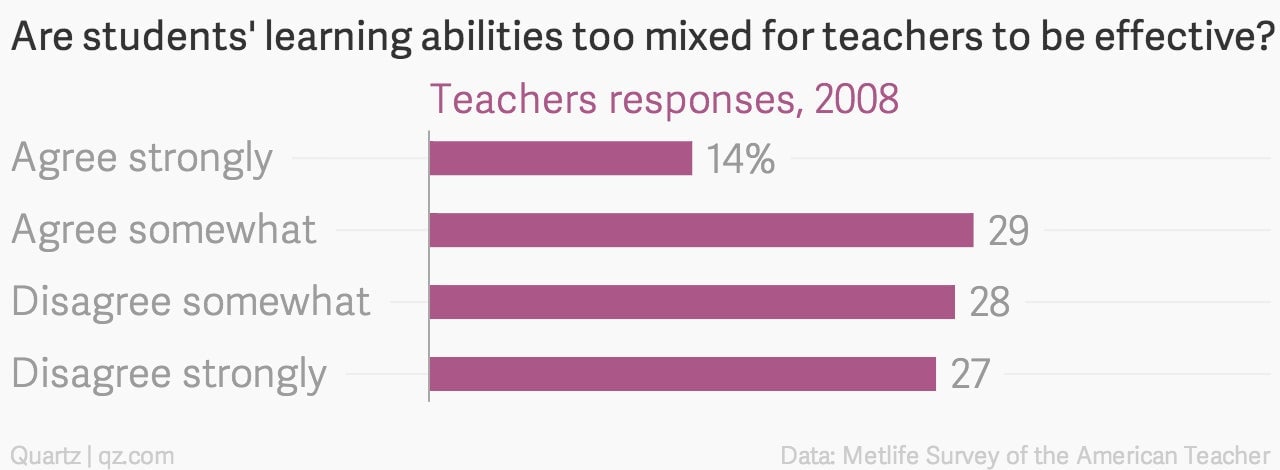

Even as the tide appears to be turning against tracking, there’s one group that isn’t on board with getting rid of the system: teachers (or at least a large portion of them). A 2008 survey of American teachers (pdf, page 62) found that 43% agree to some extent that their classes are too mixed in terms of ability for them to teach effectively. Eliminating tracking might be effective in small classes where teachers can give personal attention to a manageable group of students, but budget constraints—in New Jersey and in many districts around the country—mandate a high student-to-teacher ratio.

There are also other ways to open up higher level classes to all students without completely ending tracking, says Daugherty of the South Orange Maplewood School District. One is to standardize the system for testing into advanced tracks, rather than leave it to students and their parents. A few years ago, the district required all sophomores to take the AP English qualifying exam—and then followed up with the students who did well but did not enroll. Instead of making the test optional, favoring students and parents who are knowledgeable about the system and assertive, this system can help identify innate talent, the theory goes.

Another option would be to remove barriers to entry in the advanced classes altogether, and to allow students to self-select their classes instead of test into them.

Students do learn at different paces, Theokas says: That is important to understand and accept in order to bring equality into the classroom. They do not, however, learn at different paces based on their race.

But for parents like Fields across the country, that’s what they see when they drop their children off at school every morning. “You see kids entering the building through the same door,” Fields says. “But the second door they enter is racially stratified.”

Correction (Nov. 21): A previous version of this post incorrectly stated that all freshmen in the South Orange Maplewood School District took the AP English qualifying exam. In fact, it’s all sophomores who took the exam. We have also clarified a statement by the district’s board of education president, Beth Daugherty, regarding its demographics.