This is the ideal formula to calculate startup pay

This post originally appeared at First Round Review.

This post originally appeared at First Round Review.

When Molly Graham joined Facebook, the company already had 400 employees, but there was no official performance or compensation system in place. There had been attempts, but nothing stuck. The result: Very little transparency, a lot of one-off compensation decisions, frustration and confusion. Working closely with Sheryl Sandberg and HR chief Lori Goler, Graham set out to change this by going back to the basics.

“It gave us a chance to start from the beginning and say to everyone, ‘Okay, here is how salary works. Here is how equity works. Here’s how bonuses are calculated. We’re using formulas for all salary increases from now on. Here are the multipliers based on performance,’” she says. “People frequently find compensation and performance management overwhelming or bureaucratic, but we got such a positive response when we implemented this first system and explained it to the company. People were grateful. A system that was relatively simple, clearly communicated, and fair made a huge difference.”

Graham emerged on the other side realizing how valuable a solid, standardized compensation system can be. Today, as Head of Business Operations at Quip, she believes that there is a simple, scalable, transparent compensation system that will work for almost all startups. Here, she shares some of her golden rules for compensation and the system that she thinks strikes the fine balance between a startup’s needs and keeping employees happy.

Since joining the startup world, Graham has talked with a lot of startup founders who struggle with compensation questions like:

- What do you offer to a new hire, particularly a senior leadership role? What if they ask for more?

- What do you do about one-off salary or equity increase requests?

- What do you do about a high performing recent graduates?

- How and when should you offer increases or promotions?

- Should you counter offer if one of your employees gets a higher offer?

“I was lucky to learn from the leadership at Facebook and people like Sheryl, and now I see a lot of founders and start up CEOs spending (or frankly, wasting) a lot of time handling one-off compensation requests or new hire offers, and I desperately want to save them the time,” she says. “In my opinion, compensation isn’t something you should spend a lot of time on in the first couple years of a company. As a CEO, you should be focused on making your company successful, which in turn, makes the equity more valuable. That is what you and your employees should spend all your time on.”

Some Golden Rules for Compensation

1. No one is ever happy with compensation, and compensation has never made anyone happy.

“This is honestly the number one trap that people fall into with compensation,” Graham says. “Compensation is never going to be the thing that makes people join or stay at a startup long-term (or any company), nor should it be. Compensation is not a healthy version of retention. I know it’s terrifying when someone has a huge counter offer, or you’re trying to recruit that senior leader from a big company, but you should accept upfront that it’s better if they join for the people, buy into the vision, etc., and have to make a hard decision on compensation. They will stay longer. Your goal should be to get compensation off the table—make sure that they can live on their salary and have a fair slice of equity—so employees don’t think about it except maybe once a year. The best way to do that is to be fair and transparent.”

2. People always find out what everyone else is making.

Never build a compensation system that assumes people won’t know what their peers and teammates are making. They always find out.

“Ask anyone who has managed a team of over ten people—everyone finds out eventually, and the problem is that feelings about compensation are relative not absolute,” says Graham. “You might be living really well. You might be in the wealthiest 1%, but if there’s someone sitting next to you who makes twice as much, you’re going to feel insulted. It’s just a fact. So take that into account when you’re creating your plan. You need to be able to explain (and defend) everything through a logical set of guidelines.”

If you’re leading a small, early-stage company, Graham recommends being as transparent about what people are making as possible. This will put out fires before they start, establish an honest environment, and serve as a nice forcing function for you:

“You can’t be transparent if you’re not paying fair, and if you are, there’s no reason to not be transparent.”

It gets harder to be transparent as a company grows, so take advantage of the moment while you’re small. Go that extra mile to bake this principle into your culture, even if you know you may have to ease away from it as you grow. Your most valuable employees will remember it, and it will help both recruiting and retention.

3. Create a system that revisits compensation only once or twice a year.

Startup CEOs have so much going on that they shouldn’t burden themselves adjusting people’s pay on an ongoing basis. This is the logic behind annual compensation evaluations. The single most important thing any employee can do is add value to the company, which will add value to the equity. This should be the prevailing message around compensation.

“Talking about compensation more than once a year is a waste of time for everybody when you’re small,” says Graham. “If you have a squeaky wheel on the team, you should have a frank, transparent conversation with them, and if they can’t get on board, maybe they shouldn’t be there. Build a system so you have a set time period to worry about this, communicate that system so people know when to talk to you about it, and you’re done.”

4. On the spectrum between formulaic and discretionary compensation, be as formulaic as you can.

“It’s really, really hard to predict the long-term at a startup,” says Graham. “If you start using discretion too early about new hires or new performers, you’re going to set yourself up for long-term problems you can’t anticipate.”

- What if someone who is a high performer at 10 people isn’t quite as good at 50 people?

- What happens when you need to split someone’s job in three years?

- What if you can’t offer quite as much base salary at one point than you can at another?

“You can’t predict people’s performance and the state of the business in a year. It’s a good idea to be conservative.”

“The name of the game is expectation setting. From the moment you really start getting serious about a candidate all the way through you managing them for years, you want to have one process and a very consistent message,” says Graham. “One of the worst things you can do with compensation is change your message.”

At Quip, every hiring manager sits down with their prospective candidates to explain how the company manages salary and equity. Everyone gets the same talk. “We tell them, ‘Everything we do is formulaic,’” she says. “We explain how everyone in the company that has a certain amount of experience gets paid exactly the same, we explain that we don’t negotiate and see how they react.”

The system

“Before you ever give anyone numbers, you need to have a conversation about how your company thinks about compensation—salary, equity and how they’re managed,” says Graham. “Don’t jump to the numbers, first explain the framework. That will start things off on the right foot.”

The earlier a startup can put a plan in place to manage compensation conversations and questions, the fewer problems they’ll have in this area going forward. With this in mind, Graham says there are three places where a company needs to focus on compensation and have specific ideas about how to handle it.

When you hire someone

Startups have a particularly hard time towing the line at this part of the process. “Founders don’t want to draw hard lines because they feel this need to do anything to get talented people in the door, but they’ll end up paying for that decision later,” says Graham.

It’s not unusual for a young company to hire someone for twice what they’re paying other people in a similar role because they don’t want to lose the hire. But this impulse can lead to damaging imbalances, widespread unhappiness on the team, and overblown expectations for the individual.

“Most startups overpay for talent because they undervalue their own equity—so the candidate will too,” says Graham. “You have to remember that when people are joining your company, they’re making a bet on its future and the value they will add to its future. Sometimes you need to remind them they are making a bet, and that it’s the kind of bet you have to make if you want to join a 10-person company.”

To change a candidate’s perception of your equity offering, supply them with the numbers and enough information so they can estimate the low, medium and high outcomes based on public equivalents.

Equity will always be a crap shoot when it comes to market rates. 0.1% of your company is probably not equal to 0.1% of another company, so you need to help every candidate understand the potential value of the equity you’re offering them without making promises.

“No matter how smart the people who walk in the door, many won’t understand how to value their equity.” For this reason, one of the best things a founder can do really early on—either in writing or a speech at an all-hands meeting—is to educate everyone about what they’re looking at. “You can say, ‘You have 15,000 shares,’ but that’s pretty meaningless. Even 0.1% is meaningless. You should also give them the most recent valuation of the company, the number of outstanding shares and the basis point.” They can do the math from there, and you should encourage them to think both about the best and the worst case scenarios so they truly evaluate the risk they’re taking and the possible reward. First and foremost, any new hire should be looking at what their equity will be worth in 2 to 10 years, not what it’s worth today.

“At Facebook we literally put together a guide to understanding your equity when we made offers,” Graham says. “It was simple to do and made people feel more comfortable with the offers we were making.”

One of the best things you can do with new hires is not negotiate.“Negotiation on salary and equity can reward the wrong kind of people and the wrong kind of behavior,” says Graham. “If you negotiate, you’re primarily rewarding people who are good at negotiating.” This is probably not the skill set you’re focusing on hiring at an early-stage startup, and talented engineers are often not the strongest negotiators.

This can be hard when you start hiring business-oriented people because they’re hard-wired to negotiate, but you should hold firm. “At Quip, we just say, ‘Look, we base equity on your employee number and it’s a formula. We can talk about the numbers as much as you want, but we don’t negotiate on either salary or equity.’ We’ve generally gotten a very positive response,” she says.

Quip has also let candidates walk out the door because they weren’t comfortable with salary. “We know we pay competitively and sustainably (we have multiple people with families, etc.), and we want people to join because they love the product and the team. We also want to hire people who care about the company’s burn rate and know that salaries are the biggest part of that for most companies. These are hard conversations to have, but they set up a much better system and a much happier team over time.”

So what should you do? One of the simplest ways to find a fair base salary for someone is to create three different levels — that way you leave room for people to grow — and pay everyone at the same level the same amount. That makes leveling your people the only discretionary part of the system.

For equity, you also have to figure out the starting place that’s right for your company, but employee number is an easy proxy for the amount of risk people took when joining. That way you can decrease the percentage of equity you give out by a set amount for each employee that joins. Graham recommends comparing this percentage to market rates to make sure you don’t fall behind—but do keep in mind that equity is not equivalent between companies.

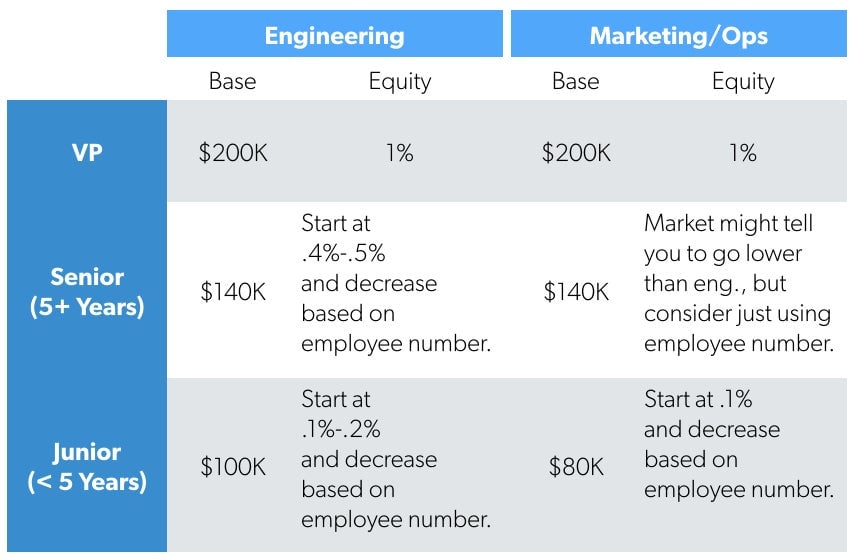

Using this system, Graham provides an example that should work for a post-Series A company:

Notably, she proposes keeping salaries the same for senior executives working in engineering and marketing/operations. This goes back to the desire for fairness, that salary information is never opaque, and the need to generate a feeling that everyone is working together to make the company a success. “Remember that if you value the business side of your company differently from the engineering side, you are sending a cultural message. That doesn’t mean it’s wrong, it’s just good to be conscious of.”

Annual milestones and performance reviews

Graham suggests reviewing compensation on a formal basis once a year for the following reasons:

- It enables you to defer all compensation conversations to just this one time.

- It allows you to do the research to ensure that all salaries are still even with the market.

- It gives you all the data you need to decide whether to offer high performers more salary or equity.

While Graham recommends scheduling compensation reviews in December or January to help people reflect on the year before and look forward to the year ahead, she says startups should do whatever is right for their business. There might be different seasonality that dictates when this should happen—ideally when people and managers have the time and energy to be thoughtful about their peers.

Every new hire should be informed that compensation reviews only happen once a year. There should be no exceptions. “The moment you break this system—even if someone has a higher offer from another company—you undermine yourself and teach people that all they need to do to get more money or stock is to ask for it or get another offer. Don’t do it.”

When you do evaluate compensation, get the market data ahead of time from your lead VC firm. You want to make sure you’re still competitive, and if you discover you’re lagging, consider a blanket increase across the board.

In addition to providing competitive salaries for the market, you should explain what that means to your employees. “What is market when it comes to compensation, and how is it defined? What does it actually mean?” Don’t leave people wondering where you got your data set or how credible you’re being on this issue.

“No one should join a startup for the cash, but you also want people to be able to live well.”

Performance reviews shouldn’t be confused with management reviews. Graham has seen situations emerge where real feedback is only provided to employees around annual performance evaluations. “At startups it’s particularly important to have a completely different framework for when you tell people how they’re doing, tell them how to improve, and give them advice for managing their performance,” says Graham. “Personally, I do weekly one-on-ones with my team and quarterly dinners with each person. I use these meetings to manage performance on an ongoing basis. You don’t want people to confuse receiving feedback with how much they’re going to get paid.”

When you don’t commit to regular check-ins, it can take way too long to spot poor performance and fire the people you need to cut from the team. It can also prolong the time it takes to bring people into new roles if someone is stretched and close to burnout. “One of the biggest mistakes a founder can make is to link compensation and performance management. They should be treated and communicated separately at every opportunity.”

Startups should avoid performance-based increases for the first couple years an employee is with the company. As an early employee, most of the value people should be getting is the increase in the value of their equity as the company grows. Giving people performance bumps will get complicated and potentially unfair fast.

As Graham puts it, everyone’s energy should be going to equity for a while — nobody should be getting raises before a Series B is raised unless it’s about getting them up to market rate. “If people are working head down to increase the overall value of the company, that increases everyone’s reward, and that should be a good incentive.”

But, the logic follows, if an increase is absolutely necessary, it should come in the form of equity — not base salary.

“When you’re thinking about increases, it’s not always correct to say that someone senior inherently creates more value than someone junior,” says Graham. “Model it both ways and decide what is right for you.”

If you decide to do equity increases, she suggests that startups determine a number of shares they want to pay out to everyone based on the current pool and valuation. “In addition to the pool, you should decide on a number of performance ratings — usually 3 ratings is sufficient for a small company.” The management team should then look at the entire employee base and assign a performance rating to each employee. This evaluation should take both their teamwork and individual work into account.

“Debate and discuss individuals and the whole team. If the company isn’t doing well, the employee performance ratings should reflect that. This is a good time to be honest and reflective.” Make your top rating special. Only put a small percentage of people in that bracket — like 1 to 2 people if you’re at 30 or less employees, or 1 to 5 if you’re at 50 or less,” says Graham. “Anyone who goes through this process and it’s clear that they’re ‘just doing okay’ should be on the path to getting fired — particularly if you’re in a phase where you’re scaling fast. It sounds harsh, but it’s usually right for the business.”

To give startups a framework to approach performance-based increases, Graham has created the following framework:

Exceptions to the rule

Once in a blue moon, a hire will come along, or an existing employee will start killing it, and you’ll want to break away from existing salary bands and formulas. This needs to trigger a very deep conversation and consideration.

“Generally speaking, exceptions are a horrible idea because everyone wants to be the exception—and remember, people will find out,” says Graham. “It reduces fairness and usually won’t actually make the person who is the exception as happy as you want them to be.”

Given these repercussions, compensation should never be your first answer in this type of situation. You should first try to think of other ways to reward people or make them feel special.

If you are dead set on going this route, however, there are a couple solutions to consider:

- “Try to make exceptions fit into the system,” Graham says. “For example, put the person at a higher level than their experience dictates — compensate a senior person like a VP, or a junior person like a senior person.”

- Make a huge deal out of the exception to the person in question (not to everyone else). They need to know that you broke your system for them and that it’s a very, very rare occurrence. This communicates both that they are indeed special, but also that it won’t happen again.

“Beware of shooting stars—junior people who turn into top performers.”

These employees should be rewarded for their hard work, but that doesn’t mean you should ignore areas where they could develop more. “Junior people who are extraordinary often don’t get enough constructive feedback, and they end up with huge weak spots,” says Graham. “If people are always told they’re the best of the best of the best, and you reward them over and over again, they’ll begin to expect it. It will become the new normal. They will end up leaving the company sooner than you want them to because they can’t continue on the trajectory you’ve set up for them forever.”

To prevent this situation, she suggests founders and managers create guidelines for themselves so they check whether they are “over-rewarding” certain employees. You might have to restrain yourself, but it will be better for the people themselves and the company in the long run. “It’s hard to catch the long-term problem before it’s too late unless you plan for it upfront.”

The one core exception to all of these rules (and it’s a big one) is how to compensate sales staff. This is a different animal altogether because you have to build in incentives that impact base salaries and equity. Here, Graham recommends Jason Lemkin’s plan for setting initial sales compensation numbers. The basics of this approach include:

- Offering competitive base salary: The catch is that the salesperson needs to bring in the revenue to cover it and their benefits before they can receive any bonus, including commission.

- Paying twice as much in commission: If reps do pay their base back first and 80%+ of reps hit their numbers, you can afford to pay out 20% to 22% in commission instead of the standard 10% to 11%. This makes hitting goals all the more compelling.

- Paying more for cash upfront deals: Some deals will come in the form of cash and some won’t. To motivate reps toward the former, pay out more for cash upfront deals and less for the rest. This makes pulling in cash top of mind for everyone.

- Paying upon receipt of cash, not contract signing: This helps align everyone’s interests because you’re offering to pay a pretty hefty sum for high performance while also instilling the value of keeping the company healthy first. Reps might hate the cash-first approach, but they’ll appreciate why you’re doing it.

For all technical, marketing, operations and other roles, Graham says her system will create the same effect: Keeping people connected to the success of the overall company without worrying about whether they’re being fairly compensated.

To scale Graham’s plan:

- Keep adding more levels as you increase headcount and people climb the ladder of performance over years at your company.

- Add more rating categories so you can get more nuanced and precise about performance-based increases.

- Make sure you always adjust to the market once a year so that you know for sure that what you’re offering is fair, and that your employees are set up for success in their lives outside the office.

- Don’t make exceptions unless you absolutely have to. The more exceptions you make, the greater the disparity will get as time passes and the company grows.

- Consider adding a discretionary equity pool once the company gets bigger so managers have a tool to manage high performers and exceptions.