The global story of mobile connectivity, as seen in South Africa

South Africa got its first mobile phone connections in 1994, with services from Vodacom and MTN. The price war started even before services went live, with both providers cutting their rates just before launch to 1 rand ($0.27 then, $0.09 today) per minute at peak times and half that during off-peak hours. Each also charged roughly 125 rand (before tax) as a monthly subscription fee.

South Africa got its first mobile phone connections in 1994, with services from Vodacom and MTN. The price war started even before services went live, with both providers cutting their rates just before launch to 1 rand ($0.27 then, $0.09 today) per minute at peak times and half that during off-peak hours. Each also charged roughly 125 rand (before tax) as a monthly subscription fee.

Two decades later, per-minute call rates prices have risen, but not by much. While the peak and off-peak pricing structures have vanished, rates now stand at 0.79 rand per minute for pre-paid connections and 1.25 rand on contract, according to data compiled by mybroadband.co.za, a South African site aimed at the IT crowd. Moreover, monthly subscription fees have vanished, making owning a phone significantly cheaper.

Even without taking monthly subscription fees into account, however, South Africa’s call rates are a good example of how mobile connectivity steadfastly refuses to keep pace with the broader basket of consumer goods. In the 20 years to 2014, South Africa’s average annual inflation rate stood at 6.2%. By contrast, mobile phone call rates rose a mere 0.7% per year over the same period:

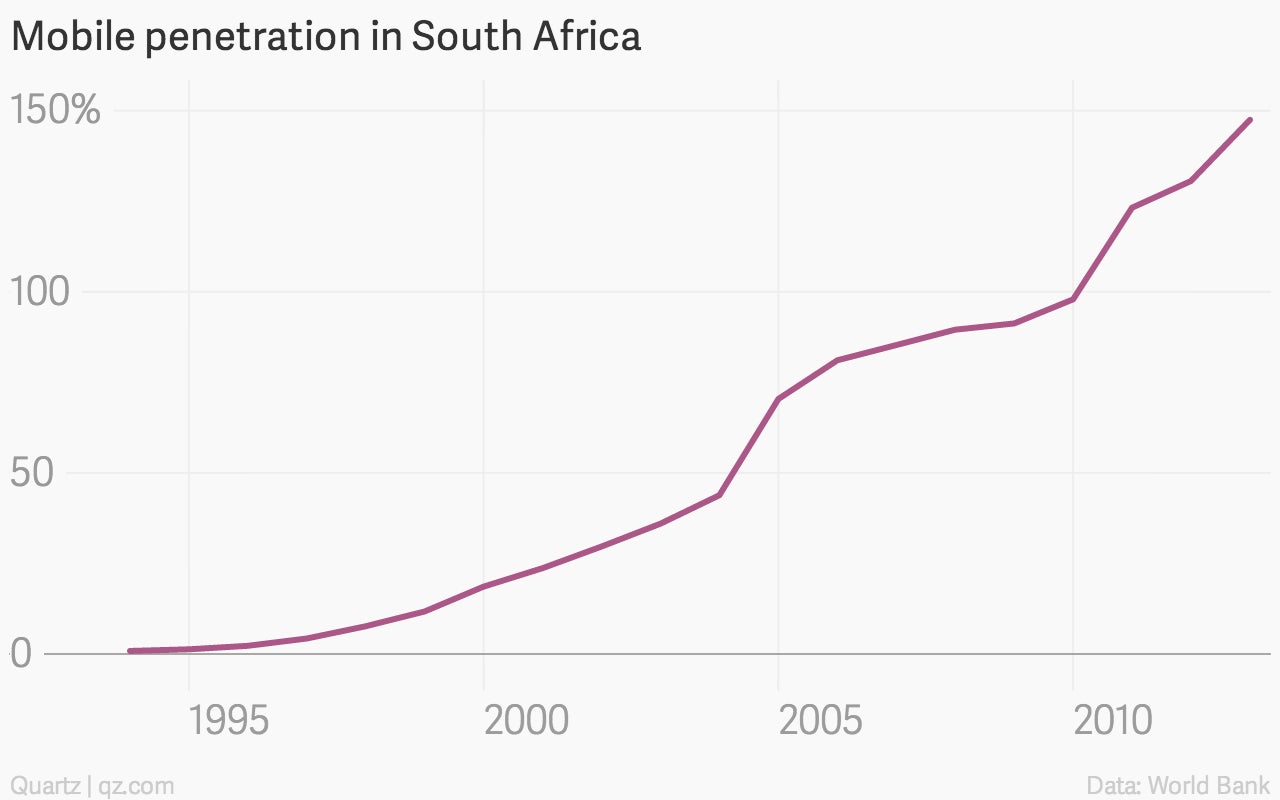

Meanwhile, mobile phone penetration rose from 0.8% in 1994 to 147% in 2014, according to the World Bank. Penetration rates are counted on a per-subscription basis, and frequently exceed 100% because people tend to use more than one SIM card. South Africa’s unique subscriber penetration stood at 65% in 2013, according to the GSMA (pdf, p.21).

It is a similar story across the rest of the world. As more people use mobile phones, prices drop, encouraging still more people to get connected. Operators say they are seeing a similar trend with data prices. Connectivity is getting cheaper, and the trend looks likely to continue.

Editor’s Note: If you are interested in this subject, join us in New York on Nov. 5 for The Next Billion, a forum on the connected world.