How cable news changes the way Americans vote

Every day, millions of viewers tune in to Fox News and MSNBC—24-hour cable news stations that have staked out positions on opposing ends of the ideological spectrum. But how much do political biases in these channels affect viewer ideology and—in turn—voting? A new study sheds light on this question, suggesting that slanted news channels have a measurable effect on election outcomes.

Every day, millions of viewers tune in to Fox News and MSNBC—24-hour cable news stations that have staked out positions on opposing ends of the ideological spectrum. But how much do political biases in these channels affect viewer ideology and—in turn—voting? A new study sheds light on this question, suggesting that slanted news channels have a measurable effect on election outcomes.

This makes sense on a gut level. But the researchers said that the mechanism by which this happens, and how it can be measured, comes as a bit of a surprise, as does the strength of the effect. “Coming into it I was thinking, if there’s an effect, it’s small,” says Ali Yurukoglu, a Stanford Graduate School of Business economist, who conducted the study with Gregory J. Martin, a Stanford PhD student at the time of collaboration. The numbers, however, showed otherwise.

Improving the model

Yurukoglu’s research began where another study left off. An earlier, and quite influential, research paper studied the so-called Fox News effect on the 2000 election by looking at which areas either had or didn’t have access to the channel in 2000 (Fox News started programming in 1996). The researchers then compared the voting patterns in those areas against the 1996 election, and came to the conclusion that Fox News persuaded a sizeable amount of its viewers to vote Republican.

During research Yurukoglu conducted on à la carte pricing for cable operators, the Stanford scholar become aware of what he says is a flaw in the data set used by that study—essentially, many more areas actually had Fox News in 2000 than were reported. He became interested in seeing if he could replicate the findings with a better model.

“The difficulty is if you just look at the data, you see people watch Fox News and you see people vote Republican—you find a correlation,” Yurukoglu says. “And what can you make of that? It doesn’t mean that they’re persuaded to vote Republican because they watch Fox News. The causality could go either way—it probably goes both ways.”

Crunching the data

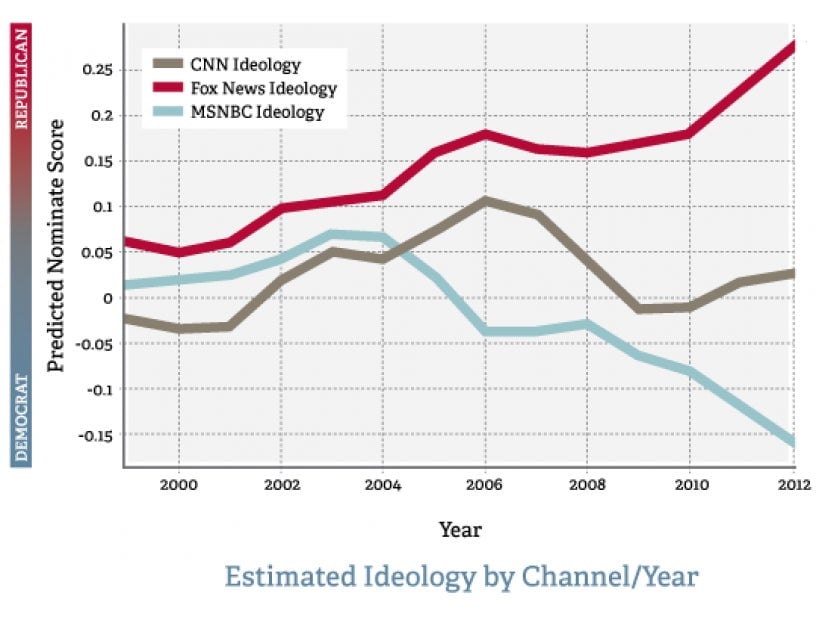

The researchers studied Fox News, CNN and MSNBC from 1998 to 2012 to find that Fox’s ideology continually shifted farther to the right, while MSNBC shifted farther to left, particularly after the mid-2000s when it changed its business practices to focus more on Democratic interests.

Yurukoglu and Martin set out to address two central questions that they hoped could help determine how watching biased news affects voting. First, how much does watching slanted news alter one’s ideology (and therefore one’s voting preferences)? And second, how intense are viewers’ tastes for like-minded news that conforms to their own ideology?

Their novel approach looked at the ordinal channel position that each cable news channel occupies in local cable lineups. Due to a variety of factors, channels with lower numbers in a cable lineup tend to be watched more than channels with higher numbers. Indeed, the researchers estimate that moving a channel’s position from the 75th percentile to the 25th percentile would increase viewership by 10%. In addition, local cable operators do not appear to give certain channels more favorable placements to line up with the ideological tendencies of their districts (meaning, Fox News doesn’t occupy a more desirable spot in predominantly Republican ZIP codes).

Studying the ordinal position of the channels, in combination with several other data points, allowed the researchers to determine how watching more or less of the biased channels impacted voting behavior.

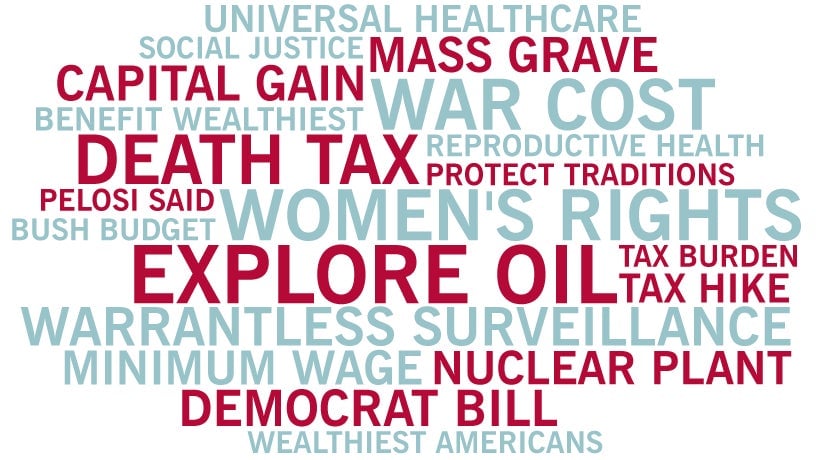

The researchers compared language used by Fox News, CNN, and MSNBC with the language used by members of Congress to quantify each station’s ideological bias (see examples, above). They found Fox News was more conservative and moved more to the right every year. MSNBC measured as fairly centrist until the mid-2000s, when it began to lean to the left after a change in business strategy.

The researchers combined channel information by ZIP code, provider, and year (for 1998-2008) with:

- Viewership data on hours watched by channel and year;

- Surveys on viewers’ intention to vote Republican in presidential elections;

- County-level presidential vote shares;

- US Census demographics by ZIP code;

- And, finally, a measure of the ideological position of Fox News, MSNBC, and CNN (see chart).

Their resulting statistical model allowed them to separately gauge the strength of the two effects, taking into account voters’ initial ideological stance, how much they choose to watch biased news (if at all), and how much they are induced into watching more or less of a channel given its position in the lineup.

The researchers were able to establish that cable news can, in fact, measurably increase polarization. They estimate that an initially centrist voter who watches an extra hour of Fox News per week would be up to 7% more likely to vote Republican, depending on the election. On the other side, that centrist voter watching an extra hour of MSNBC would be up to 7% less likely to vote Republican.

An initially centrist voter who watches an extra hour of Fox News per week would be up to 7% more likely to vote Republican, depending on the election.

Applying their model to real-world contexts, they estimate that if you simply removed Fox News from cable programming during the 2000 election cycle, the average county’s Republican vote share would have decreased by 1% to 2%.

If a percentage point or two sounds minor, recall the size of a hanging chad in 2000, when a narrow presidential election went to George W. Bush. Those numbers can suddenly look as hefty as a wrecking ball.

Ongoing questions

One of the key takeaways from Yurukoglu and Martin’s study is that the two mechanisms—the influence of biased news on ideology, and the taste for like-minded news—interact in a way that makes possible a feedback loop: Viewers consume slanted news, shift their ideologies in that direction, develop a greater taste for it, and so on in an echo chamber of even greater polarization. This could be especially prevalent with Fox News and MSNBC growing more popular and more ideologically extreme with each passing year.

This possibility makes Yurukoglu think that there could be very real implications on the public policy front.

“If consumers simply prefer news that resonates with their pre-existing ideology,” the researchers write, “then the news media sector is similar to any other consumer product, and should be treated as such by public policy. However, if consuming news with a slant alters the consumer’s ideology, then public policy toward the news media sector becomes more complex.”

Imagine a scenario in which an interested party that owns or controls media companies in critical districts could move one biased news channel into a favorable location in the lineup while burying the opposing channel deep down—and by so doing tips the scales of an election.

At the very least, Yurukoglu believes that entities like the Federal Communications Commission should be thinking about this sort of thing in light of big media mergers, such as the one between Comcast Corp. and Time Warner Cable currently under review.

“I think it makes sense to aim to put slanted news media near each other,” Yurukoglu said. “You can’t stop people from watching what they want to watch, but you can at least try to level the playing field.”

This post originally appeared at Stanford Business.