When the Yakuza come calling, one in five Japanese companies admit to paying them off

Roughly one in five Japanese companies shaken down by the yakuza ended up paying them off, according to a study released by Japan’s National Police Agency. Of the companies that answered the NPA survey, at least five had paid more than ¥5 million ($61,000) to meet the demands of yakuza extortionists. The survey gives a good indication that Japan’s “nine-fingered economy” is still very much in business.

Roughly one in five Japanese companies shaken down by the yakuza ended up paying them off, according to a study released by Japan’s National Police Agency. Of the companies that answered the NPA survey, at least five had paid more than ¥5 million ($61,000) to meet the demands of yakuza extortionists. The survey gives a good indication that Japan’s “nine-fingered economy” is still very much in business.

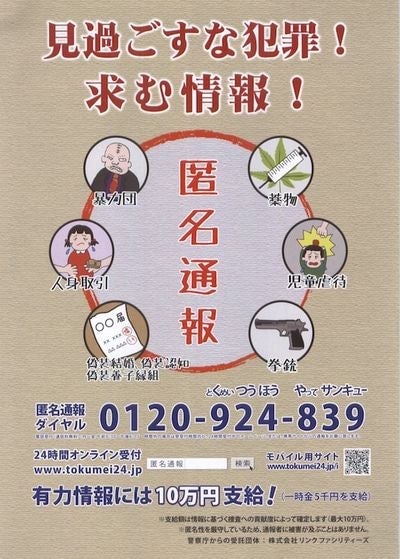

Police sources acknowledge on background that there may be more companies who actually paid off the yakuza than were willing to admit it in a police survey. In October of 2011, it became a crime in Japan to make payments to the yakuza or utilize their services under the organized crime exclusionary ordinances (暴力団排除条例). The NPA produces posters like the one below warning people not to give in to yakuza extortion demands.

Still, the periodic surveys, conducted by the NPA and the Lawyers Association of Japan, gives some of the best evidence available of yakuza activity in Japan. Of the 2,885 companies that participated, 337 or 11.7 percent reported run-ins with yakuza shakedowns. Of those companies approached by the yakuza, 62 companies or 18 percent gave into the demands. This figure is probably only the tip of the iceberg, the police say.

For the companies approached by the yakuza, more than half (185) were pressed for payments or services in the last year. Payments in cash were typically between ¥10,000 and ¥100,000 ($120 to $1,200). One company admitted to paying more ¥10 million to silence the group harassing them.

The NPA noted in the study, “Of the 2,562 companies that were aware of the organized crime exclusionary ordinances, 63.3 percent said that the laws were having an effect. When companies were asked what they wanted from the government to help cut ties to the yakuza, overwhelmingly the reply was, ‘for the police to provide information about anti-social forces’ at a little under 70 percent.”

The most common targets of yakuza shakedowns were construction companies and real estate firms. In 43 percent of the cases, the men demanding money or compensation without cause were not yakuza members themselves but individuals with yakuza backing. The four most common means of extortion were:

- finding fault with the company and demanding compensation

- asking for purchase of goods or services

- aggressively requesting donations or “association fees”

- demands for construction work and related contracts

Of the cases where the organized crime groups were clearly identified, the Yamaguchi-gumi was the top. This is not surprising with their membership at 39,000 making them the largest crime group, the Walmart of the yakuza.

88 percent of the companies surveyed were aware of the organized crime exclusionary ordinances but 1 in 4 had taken no real steps to implement compliance measures. For the companies that refused to give in to yakuza demands 32.6 percent saw their business operations disrupted, their reputation damaged by sound trucks (vehicles favored by right-wing groups loaded with loud speakers which blast out music and verbal abuse), or defamatory writing on the internet (comments and postings like “Company X’s product causes cancer” or “This corporation pollutes the rivers”). Ironically, sometimes the yakuza actually do correctly point out serious problems with Japanese corporations. According to the book, Japan’s Great Taboos 2 (Takarajima), circa 1990 a Yamaguchi-gumi boss wrote a series of articles about safety problems at the Tokyo Electric Power Company (TEPCO) Fukushima Nuclear Power Plant and was paid off by TEPCO to stop writing about them. The Fukushima Power Plant suffered a triple meltdown on March 11, 2011. There were also attacks on family members or employees or trading partners. And in about 3.6 percent of the cases, the yakuza retaliated by exposing company scandals and/or company secrets in magazines and other media.

It’s not an uncommon practice for the yakuza to use the media to punish individuals or companies they deem uncooperative. Japan’s last Justice Minister, Tanaka Keishu, was forced to resign on October 23 after his yakuza ties were exposed by the weekly magazine Shukan Shincho; the information was allegedly proffered to the magazine by his former yakuza benefactors, according to police sources and magazine reporters.

The National Police Agency predicts that there will be an increase in extortion demands from yakuza associates or yakuza-backed right wing groups or fake non-profit organizations in the next year. It mirrors increased violent resistance by the yakuza as the new anti-crime group laws put the squeeze on their regular revenue.

In the last year, as the organized crime exclusionary ordinances have been enforced, there have been more than ten reported assaults on civilians or companies by what are believed to be yakuza groups. In Kyushu (Southern Japan), women running nightclubs that barred yakuza members had their faces slashed this summer. None of these cases have been solved. The National Police Department has dispatched an undisclosed number of officers to the area to contain the growing yakuza violence there.