Photos: The people who thought their lives couldn’t get any worse—until Russia invaded

Editor’s note: Among the roughly 2 million people living in Crimea when Russia annexed it earlier this year were several hundred intravenous drug users. Under Ukraine’s rule, they had been getting substitution therapy—typically, methadone or buprenorphine in place of opiates such as heroin—which is a widely accepted way of treating addiction in much of the world. But it’s illegal in Russia, where even needle-exchange programs to prevent the spread of disease are viewed with suspicion. As a result, drug users in Russia are at very high risk for HIV, hepatitis and tuberculosis (TB), and get dumped in hospital TB wards in appalling conditions.

Editor’s note: Among the roughly 2 million people living in Crimea when Russia annexed it earlier this year were several hundred intravenous drug users. Under Ukraine’s rule, they had been getting substitution therapy—typically, methadone or buprenorphine in place of opiates such as heroin—which is a widely accepted way of treating addiction in much of the world. But it’s illegal in Russia, where even needle-exchange programs to prevent the spread of disease are viewed with suspicion. As a result, drug users in Russia are at very high risk for HIV, hepatitis and tuberculosis (TB), and get dumped in hospital TB wards in appalling conditions.

“Intravenous drug users are among the most vulnerable groups in Crimea now,” says photojournalist Misha Friedman. ”But international NGOs are wary of taking on the problem because drug users aren’t like ordinary refugees. They’re complicated—very ill adults who’ve often spent decades in prison. Some money reaches them, but nobody knows what to do with them. And they don’t stay in one place like some other refugee groups, but are dispersed.”

Since the annexation, some of these people have stayed in Crimea and tried to wean themselves off drugs. Others have moved to parts of Ukraine still under Kyiv’s control, where they can get substitution therapy. But it’s become much harder for them to obtain their prescriptions and find work. Friedman, who visited Crimea in the summer, returned to Kyiv for Quartz last month and captured the plight of the people who, among all the losers from Russia’s annexation, find themselves at the very bottom of the pile.—Gideon Lichfield

Ira 38, and Yuri, 47 (in the bed), have been a couple since 2000 and drug users about equally long. They spent two years on substitution therapy in Simferopol, the Crimean capital, before the program closed with the Russian annexation. Since May, they have been in Kyiv. An NGO pays their rent and a daily subsistence allowance, but it’s not clear how long that will continue. Ira had worked for five years at the post office in Simferopol, and was up for a promotion. In Kyiv, she is looking for similar work, but has to travel across town every day to pick up a prescription, making it impossible to hold a steady job.

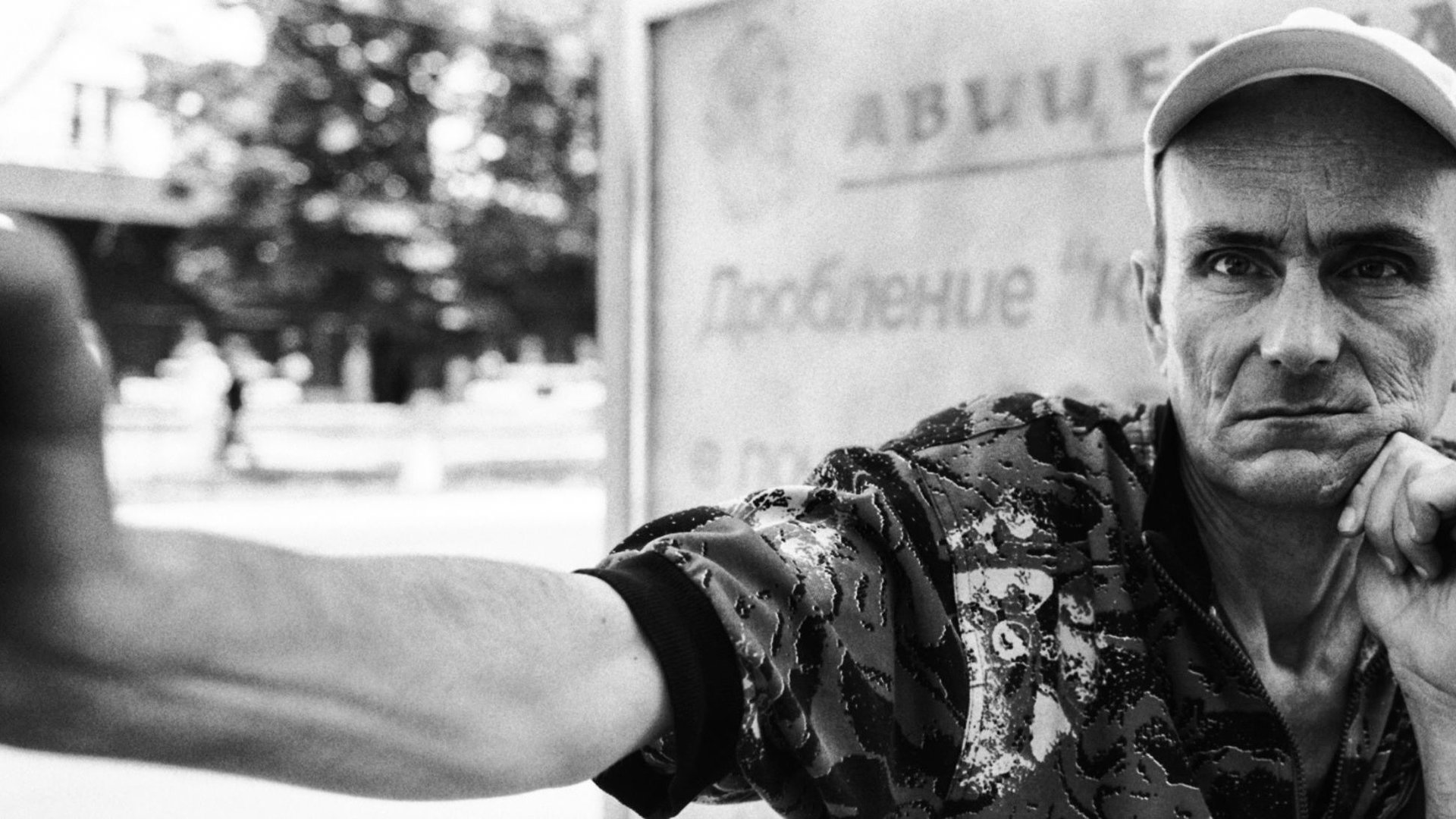

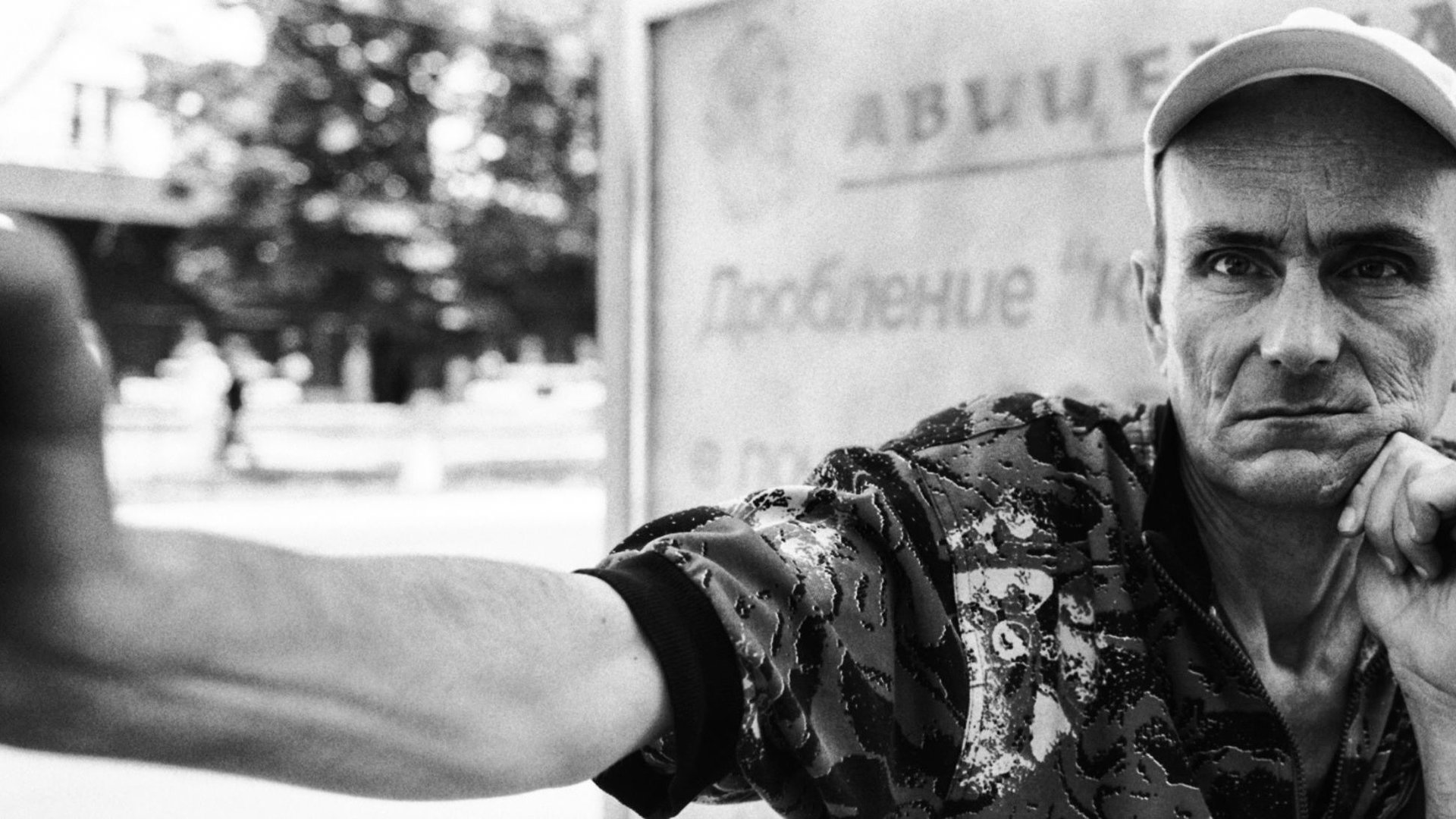

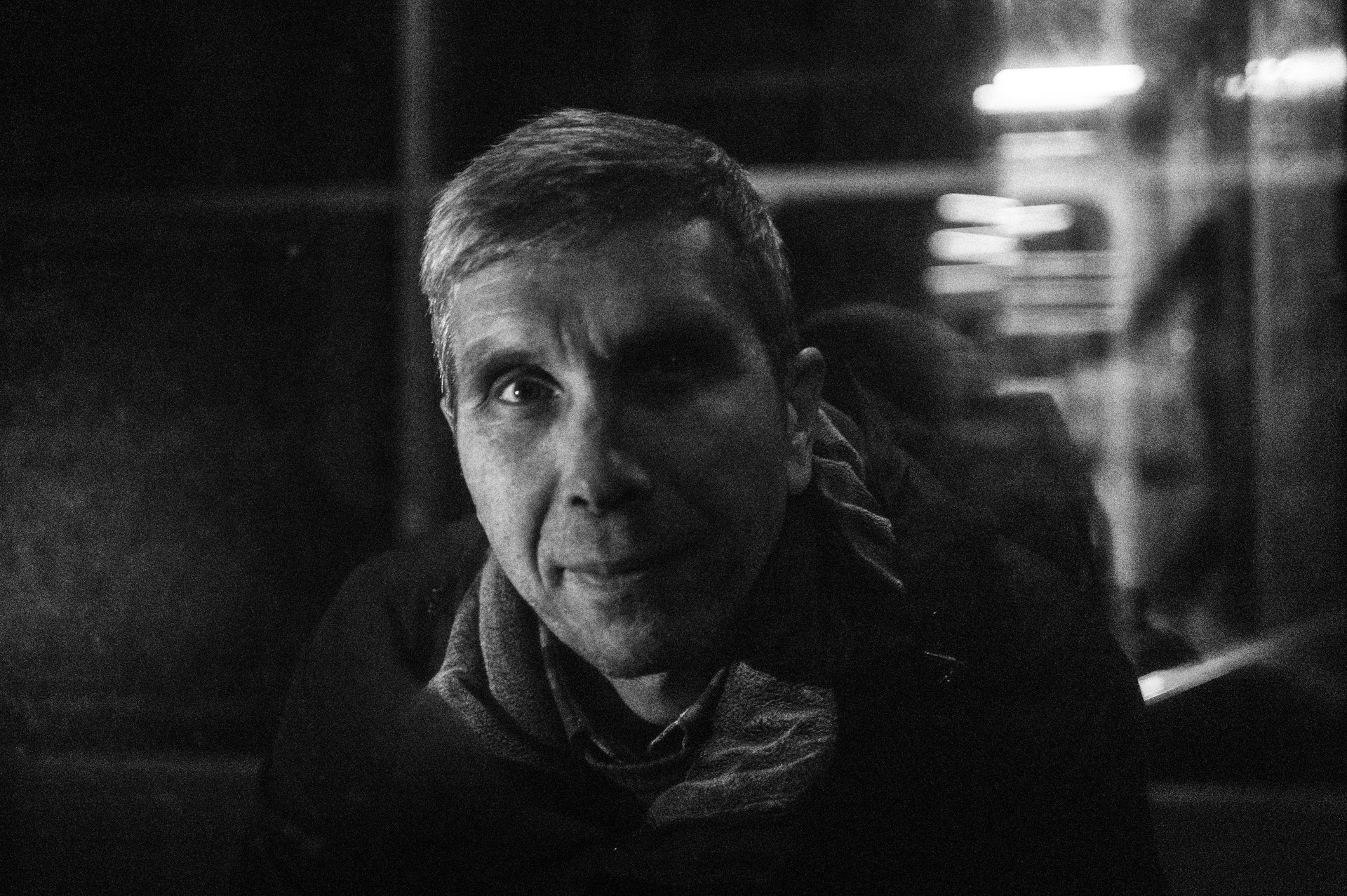

Igor, 49, pictured at the top of this piece, is a small-time criminal: “I’ve never lifted anything heavier than a wallet,” he told Friedman. He stayed in Crimea after the annexation, saying that he was going to try to turn his life around and stop using drugs. Friedman noticed a tattoo on his left thumb: “I thought at first it said LOVE. He didn’t know what I was talking about. In Russian, it reads ЗЛО (“zlo”)—evil.”

Georgiy—or Zhora, as he likes to be known—is a 28-year-old musician, who has been living in a dorm in Kyiv since the summer. At first (pictured left), he had to go to the clinic each day for his substitution therapy—a four-hour round trip. By last month (right) he had earned his doctor’s trust, allowing him to get 10 days’ worth of drugs at a time.

After getting on the 10-day regimen, Zhora was able to get a job as a supermarket cashier.

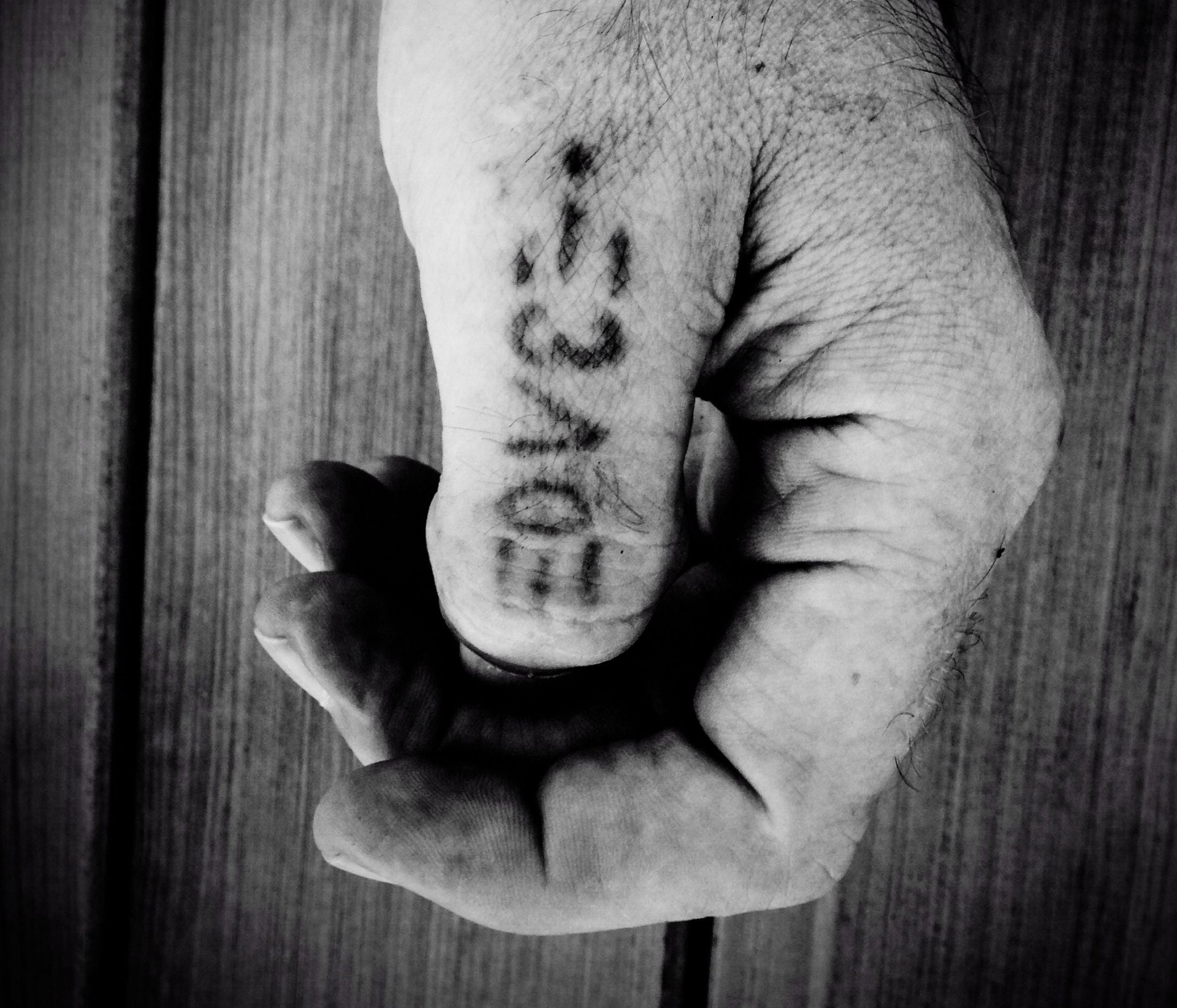

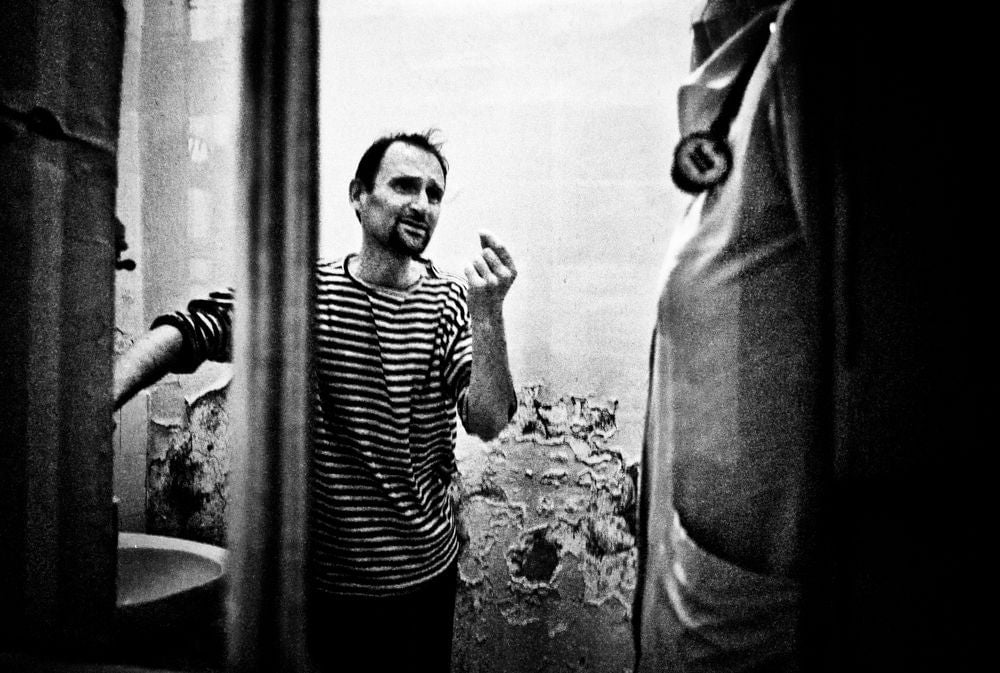

A man speaks to a friend inside the rehab clinic in Simferopol, before the substitution therapy program was closed down.

Aleksei (not his real name), 46, from the Crimean city of Sevastopol, has been a drug user for 25 years and on substitution therapy since 2008. A social worker who also makes advocacy videos, he has enough credibility to get a multi-day prescription on his visits to the clinic in Kyiv, so he is able to travel between Crimea and Kyiv and work with drug users in both places.

Irina dresses her 23-year-old son Evgeniy (Zhenya), who lost both his arms in a childhood accident, at their home in Crimea in the summer. A drug user for almost 30 years, Irina is raising three sons from two husbands. Since the annexation she no longer gets substitution therapy, but for now, they are staying in Crimea, and she is trying to get by without the treatment.

Zhenya has prosthetic arms, which rarely come out of the wardrobe.

Unless he needs to fill the sleeves of a shirt, he goes without them, as they’re completely non-functional.

Zhenya was upbeat about the Russian annexation—he thought his disability benefits might go up.

Andrei and Oleg, seen here in an accidental double exposure, are a gay couple in Simferopol, Crimea. “Theirs is one of the weirdest stories I came across,” says Friedman. They were social workers, working with both LGBT people and drug users. Russia’s annexation not only shut down the programs and cost both men their jobs; it also made Crimea subject to Russia’s notorious “homosexual propaganda” law, which essentially makes any public discussion of gay issues a potential crime. And yet they said they were happy the Russians came. “Their view on the gay propaganda law was ‘it’s fine, it doesn’t affect us, we’re against pedophiles,'” says Friedman in disbelief.

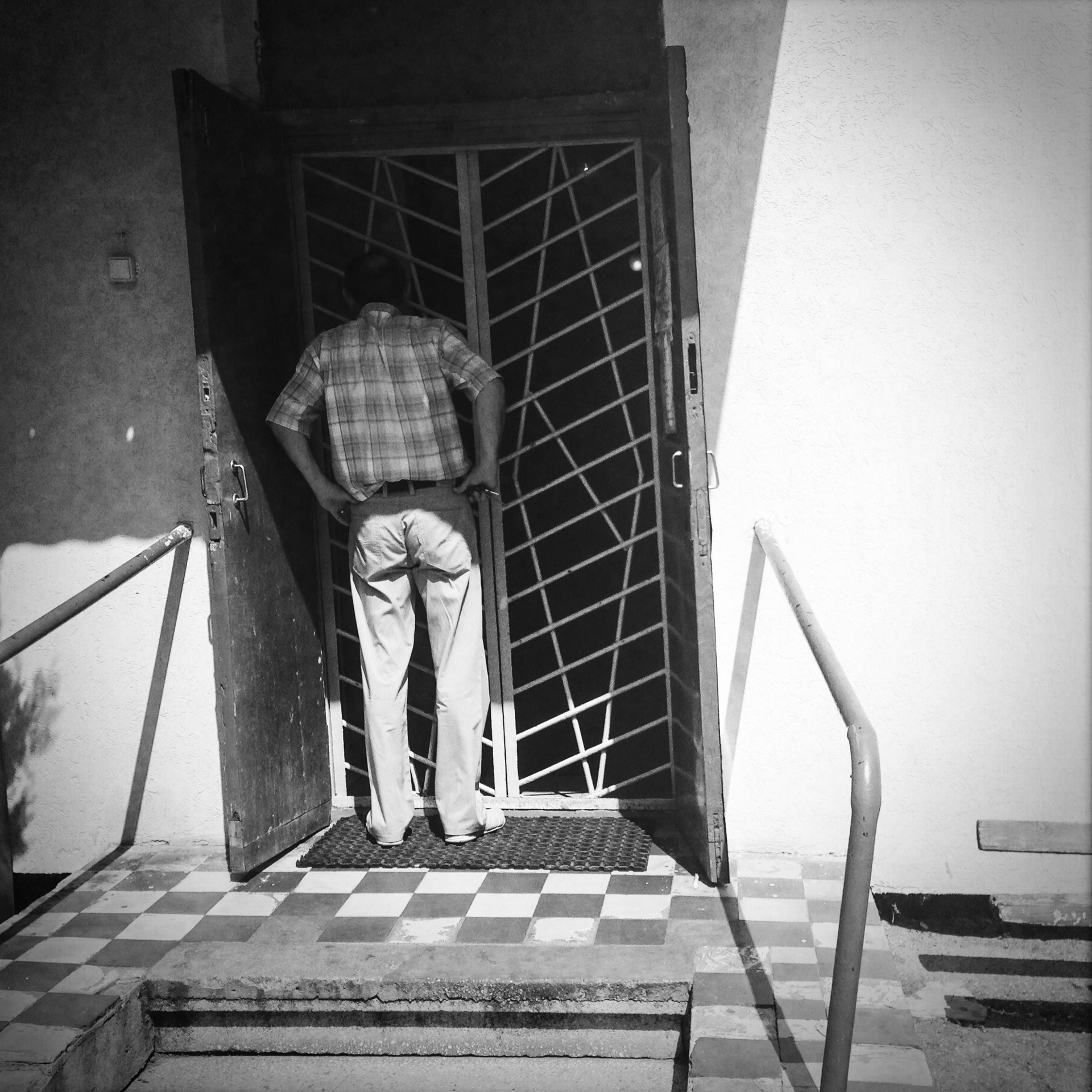

In August Friedman photographed a gay couple in Sevastopol as they prepared to leave Crimea for Kyiv. Behind the house next door, he found the yard littered with drug paraphernalia.

A man waiting to exchange needles and to be tested for HIV in an outreach bus on the outskirts of St. Petersburg, in 2011. It’s one of the very few needle-exchange programs (if not the only one) still operating in Russia, funded by foreign money and under constant threat of closure.

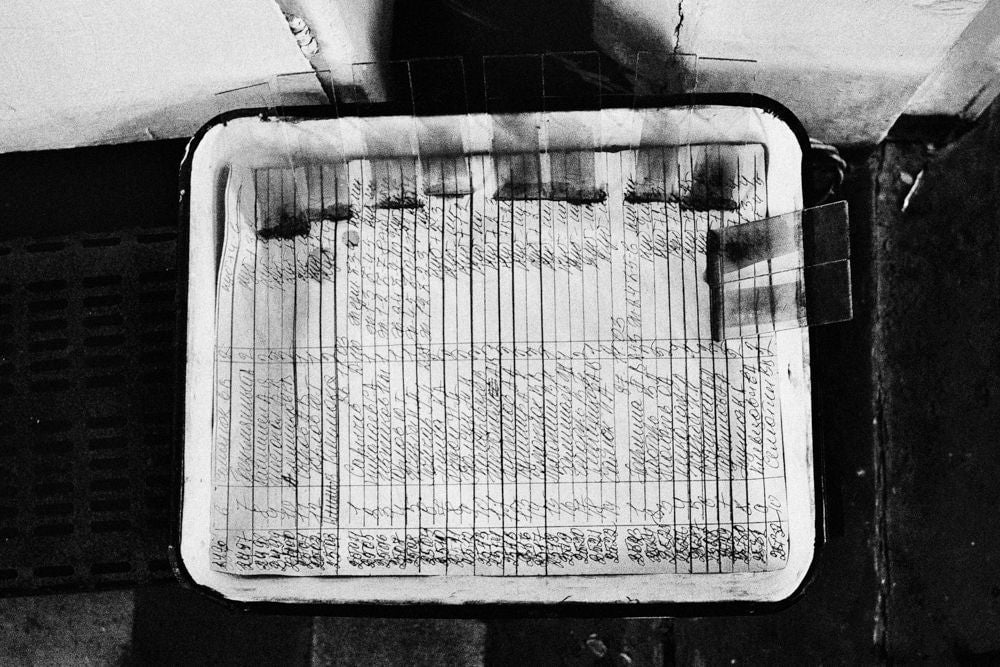

Blood samples smeared on glass slides rest on top of a sheet of handwritten lab results in a hospital in Donetsk in 2011. Both Russian and Ukrainian hospitals are severely under-equipped.

A TB patient and intravenous drug user begs a doctor for painkillers at St. Petersburg’s Botkin Hospital, in 2011. “These are the patients other TB hospitals don’t want to take because they have HIV, hepatitis C, and other diseases,” Friedman says. “When I visited there were 54 patients and only 40 beds.”

Paulina, a 37-year-old who was brought into the hospital with severe malnourishment. “She had TB, hepatitis C, HIV—the complete set,” says Friedman. Russia’s retrograde attitude to drug users makes them exceptionally vulnerable to picking up such diseases.

Friedman’s work was funded partly by a grant from the Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting.