BRICs are getting a "raw financial deal" from a low yield world

Brazil, Russia, India, and China (the so-called BRICs) aren’t too happy with rich-world central banks right now. Brazilian Finance Minister Guido Mantega loudly complained on September 18 that the Federal Reserve’s newest round of quantitative easing—purchasing low-risk mortgage-backed securities to push down long-term yields on “safe” assets—would have damaging effects on emerging market economies. In particular, he worried, the value of emerging-market currencies would rise against that of their trade partners, decreasing their exports.

Brazil, Russia, India, and China (the so-called BRICs) aren’t too happy with rich-world central banks right now. Brazilian Finance Minister Guido Mantega loudly complained on September 18 that the Federal Reserve’s newest round of quantitative easing—purchasing low-risk mortgage-backed securities to push down long-term yields on “safe” assets—would have damaging effects on emerging market economies. In particular, he worried, the value of emerging-market currencies would rise against that of their trade partners, decreasing their exports.

But Deutsche Bank analyst Markus Jaeger explains that there’s another reason BRICs are angry at the Fed and its counterparts: they’re highly invested in developed-world government bonds such as US Treasuries. Central banks in emerging markets accumulated those bonds in an attempt to fight a “currency war” against deflating developed-world currencies (and each other) to keep exports cheap. Now, Jaeger writes, these governments are “getting a proverbial raw financial deal, at least from an external cashflow point of view.” Simply put, the debt they hold now yields a lot less than the price they have to pay to borrow. Jaeger explains:

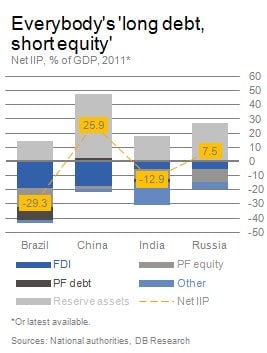

All BRICs – like most other emerging economies – are ‘long debt’ (mainly in the form of reserve assets) and ‘short equity’ (FDI and portfolio equity). A large share of foreign assets therefore consists of low-yielding foreign government debt securities, and a significant share of liabilities is made up by generally high(er)-yielding equity investments, the combination of which translates into poor financial returns…This balance sheet structure is largely due to (past or present) controls on private capital outflows and the desire among emerging economies to accumulate official reserve assets – either as a form of insurance against balance-of-payments shocks or as the byproduct of persistent currency intervention in the context of an undervalued exchange rate.

Put another way: BRIC countries’ balance sheets are still full of rich-world bonds. At the same time, they have (or had until recently) capital controls meant to promote domestic investment, which stop private BRIC investors from investing in foreign instruments that might give them a higher return. While the BRICs have been liberalizing their policies, it’s taking time. Furthermore, they are still under pressure to keep their currencies cheap in order to spur exports. But keeping their currencies cheap and keeping cashflow high are, of course, directly at odds.