Why China's labor unrest isn't like the US in the 1930s. (At least, not yet.)

In a recent article on China’s growing labor unrest, Eli Friedman of Cornell University in New York compared striking Chinese workers with their counterparts in the United States in the 1930s. Both forced their governments to pass new labor laws, and companies in China have raised wages and improved conditions. But the comparison, he suggests, ends there: in China, the path that took American workers from labor demands to broader political involvement is blocked.

In a recent article on China’s growing labor unrest, Eli Friedman of Cornell University in New York compared striking Chinese workers with their counterparts in the United States in the 1930s. Both forced their governments to pass new labor laws, and companies in China have raised wages and improved conditions. But the comparison, he suggests, ends there: in China, the path that took American workers from labor demands to broader political involvement is blocked.

The future of Chinese labor resistance is on the table again after Foxconn, which makes products for Apple and is the world’s biggest electronics manufacturer, closed a plant in Taiyuan on Sept. 24, after scuffles between workers and security guards erupted into a violent riot the night before.

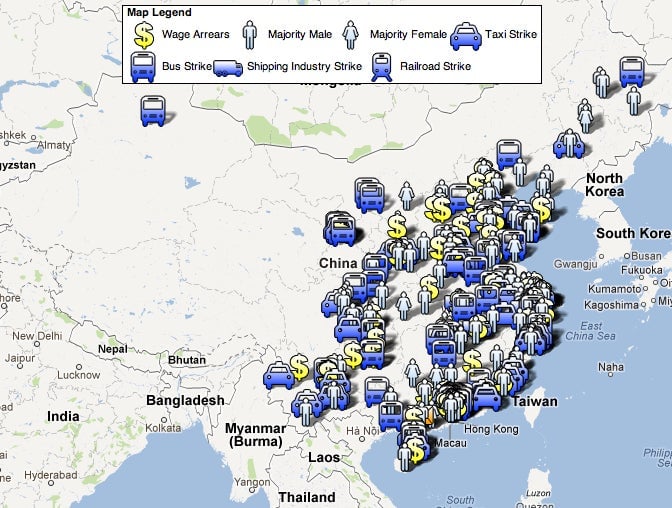

In China, already identified three years ago as an emerging “epicenter of global labor unrest” (pdf), workers have won out in several high-profile protests against factories and businesses who pay them low or incomplete wages. In 2010, a two-week strike at a Honda transmission plant in the southern province of Guangdong landed workers raises of between 24% and 34%. After a series of worker suicides in 2010, Foxconn gave employees a 30% raise.

But while some have written that this outburst of protest could lead towards more democracy, Friedman argues that the workers’ demands are unlikely to extend far beyond wage increases:

Any attempt by workers to articulate an explicit politics is instantly and effectively smashed by the Right and its state allies by raising the specter of the Lord of Misrule: do you really want to go back to the chaos of the Cultural Revolution?

In some strikes workers have begun to demand that they elect their own union representatives to the official All-China Federation of Trade Unions (ACFTU). Still, by and large there has been a “segregation of political and economic struggles,” he says.

Besides the ghost of the past, another big reason why China is not like the US is that a huge majority of Chinese laborers in the country’s manufacturing hubs are migrants from elsewhere in the country, also known as nongmin or peasant labor. Many leave their families in their hometowns. It is also difficult to get a type of resident registration called the hukou in cities, which gives workers social benefits like school for their kids. When it comes to workers’ rights, their chief and usually only concern is wages. ”In other words,” writes Friedman,

migrant workers have not attempted to link struggles in production to struggles over other aspects of life or broader social issues. They are severed from the local community and do not have any right to speak as citizens. Demands for wages have not expanded into demands for more time, for better social services, or for political rights.

All the same, the frequency of worker strikes—estimated to be in the tens of thousands absent official figures—is expected to continue and in some cases increase. The reasons are myriad: a continued labor shortage, urbanization, and a slowing Chinese economy. Friedman also points out another phenomenon: the development of China’s interior regions, which is also one of the central government’s priorities. With more job opportunities at home, Chinese workers will live and work in the same place and likely demand more for themselves and their community. Housing, health care, and protection from unemployment are some examples, Friedman says.

Moreover, Chinese laborers are not establishing institutions or unions that can bargain on their behalf. In the United States, for example, the United Auto Workers union became a political force after the 1930s labor movement and labor unions overall gained collective bargaining power, Friedman said in a phone interview.

In China, the result is that workers continue to strike over grievance after grievance, often at the same factory. “China is in for a relatively long period where there will be high levels of labor unrest because they are not developing these institutions,” Friedman said. “I think it’s going to continue for a long time.”