Big banks’ new money-saving strategy: streamlined snitching

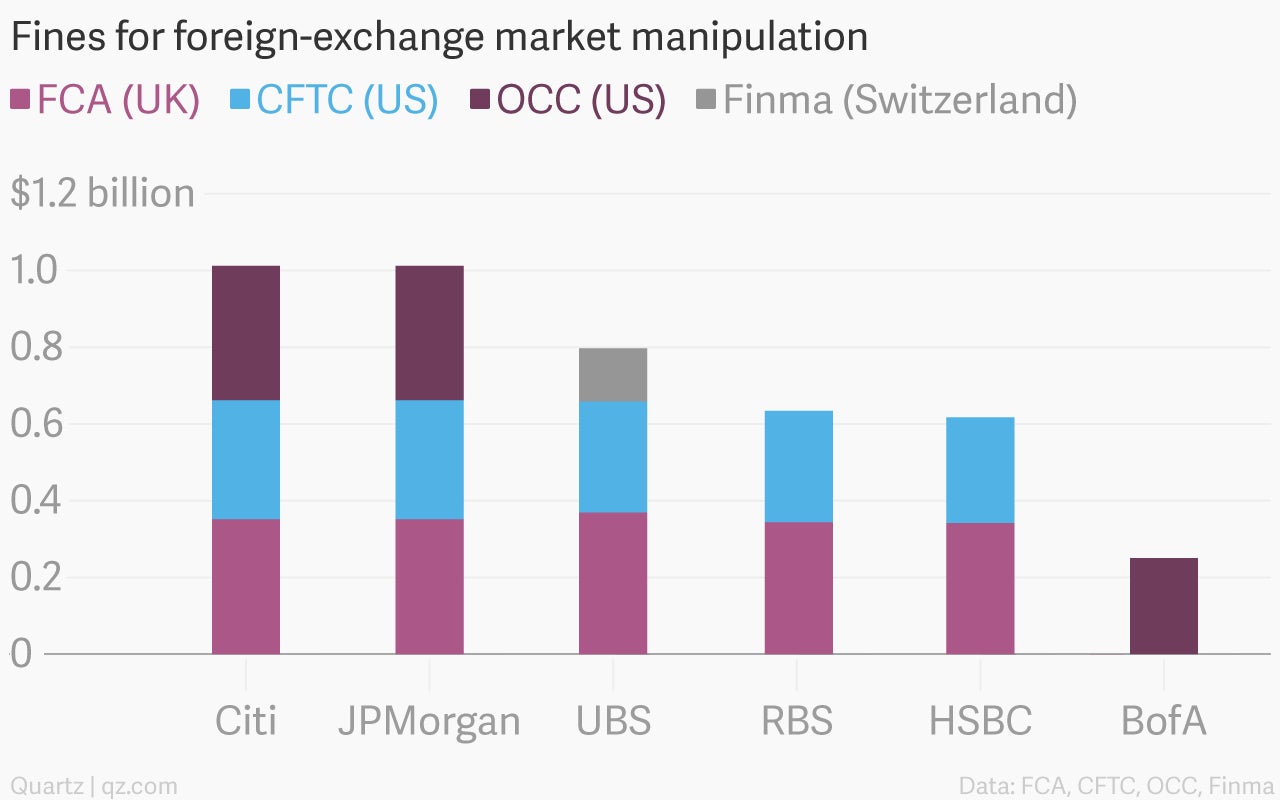

When regulators in the US and Europe hit six of the world’s biggest banks with $4.3 billion in fines yesterday, the market shrugged. After all, the reason for the penalty—attempted manipulation of foreign-exchange rates—is just the latest in a long line of misdeeds by financial firms, and put a mere dent in the huge provisions that banks have set aside to cover the costs of this and their many other legal entanglements.

When regulators in the US and Europe hit six of the world’s biggest banks with $4.3 billion in fines yesterday, the market shrugged. After all, the reason for the penalty—attempted manipulation of foreign-exchange rates—is just the latest in a long line of misdeeds by financial firms, and put a mere dent in the huge provisions that banks have set aside to cover the costs of this and their many other legal entanglements.

Shares of UBS even rose. Yes, the bank faced one of the stiffest fines—around $800 million—levied by financial watchdogs in the US, UK, and Switzerland. This included the largest-ever individual penalty (£234 million) set by the UK’s Financial Conduct Authority. (As it happens, the Swiss bank had also set the watchdog’s previous record, £160 million in 2012 for fiddling with Libor.) But the latest fine could have been worse—banks that settled with the FCA yesterday qualified for a 30% discount on their fines in return for their early cooperation with investigations.

Blowing the whistle

UBS has previous experience with this, as it dodged a €2.5 billion penalty last year from the European Commission by being the first to blow the whistle on the interbank interest rate-rigging cartel it was a part of. The way things are going, if a bank going to face a big fine—as just about every big bank will at some point, it seems—settling the case early and snitching on alleged partners in crime looks like a shrewd strategy. (The cost of not doing so is rattling shares of Barclays, which is under investigation for foreign-exchange manipulation but chose not to settle with authorities yesterday.)

As is the case with all of these big bank settlements, some of the most damning evidence comes from online chat logs between traders. Understandably, banks are eager to get a handle on what’s being said on their own message systems. RBS, for example, has said its lawyers have now combed through “millions of documents and are reviewing the conduct of over 50 current and former members of trading staff around the world as well as dozens of supervisors and senior management.”

This is music to Simon Price’s ears. He runs the London office of Recommind, which makes “eDiscovery” software for regulators, law firms, and companies (including several big banks) that can streamline searches for documents during legal investigations. Revenue at the San Francisco-based firm has soared since the beginning of the global financial crisis, Price tells Quartz.

The search algorithms developed by the firm’s data scientists have won industry plaudits, but the gist of the company’s sales pitch is that it purports to cut the cost of litigation. By speeding up the search for damning internal documents, it allows defendants to steal a march on rivals facing similar investigations, potentially gaining more lenient treatment from regulators.

Betty on the mumble

By identify connections between records and sorting them by concept, Price says Recommind’s software can surface misbehavior that would otherwise go unnoticed. A phrase as innocuous as “lunch for two” in the context of chats, emails, trading records, and other documents could reveal itself as code for something more sinister, he says. Slang is also hard to unpick, as these particularly impenetrable passages from trader chat logs released yesterday (pdf, see footnotes for translations) show:

- “you gettingt betty on the mumble still? we have nowt”

- “get lumpy cable at the fix ok”

- “i getting chipped away at a load of bank filth for the fix… back to bully … hopefully decks bit cleaner”

As confusing as these phrases are to the untrained eye, regulators say that they show intent to manipulate various markets, which is backed up by trading records and other records they can tie to the chat comments. In almost all of the regulators’ reports and banks’ statements about the foreign-exchange investigations, there are mentions of the rollouts of new monitoring systems to spot these sorts of red flags in the future.