200 years of latex clothing, from secret fetish to high fashion

Earlier this week, the Italian tire company Pirelli shared photographs from its racy 2015 calendar: the 51st in its annual series that features naked and nearly naked supermodels in seductive situations. This year, those supermodels wore skin-tight, high-shine latex, shot by fashion photographer Steven Meisel and styled by Carine Roitfeld in what many identified as a “fetish-themed” calendar.

Earlier this week, the Italian tire company Pirelli shared photographs from its racy 2015 calendar: the 51st in its annual series that features naked and nearly naked supermodels in seductive situations. This year, those supermodels wore skin-tight, high-shine latex, shot by fashion photographer Steven Meisel and styled by Carine Roitfeld in what many identified as a “fetish-themed” calendar.

“I’ve never worn latex before but everyone’s, like, telling me that it would suck because you get all sweaty and you can’t breathe,” calendar model Gigi Hadid told WWD. “But I really like it and now I want latex leggings.”

“You’re just fascinated when you put it on,” model Candice Huffine said of the experience. “Latex and fishnets just really do something to a woman, you know?”

Indeed, the material seems to be having a moment in the mainstream. Marc by Marc Jacobs’ buzzy new design duo sent latex down their spring 2015 runway in the form of polka-dotted skirts, twisted bandeaus, and flesh-toned sleeves. Belgian designer Christian Wijnants fashioned it into translucent vests. This week Kim Kardashian coated her curves in not one but two latex looks by London-based latex couturier Atsuko Kudo for her appearances in Australia.

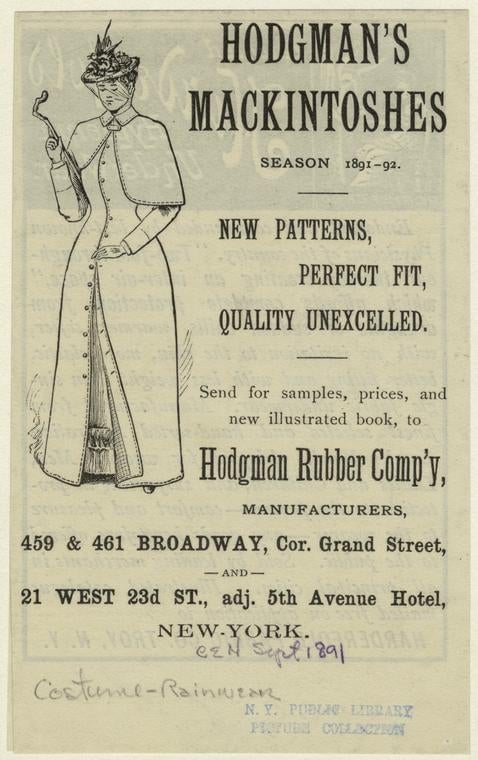

It may be fashion now, but as fetish-wear, latex is far from new. Nearly two hundred years ago, Scottish chemist Charles Macintosh made rubberized fabric to be manufactured into waterproof Mackintosh coats (whose name acquired a “k” along the way). The coats were stinky, sticky, and liable to melt if things got too hot—barely ideal for, well, things getting hot. But before long, Mackintosh coats found their way into the kinky realm previously reserved for fur, silk, and corsets, thanks in part to one of the world’s oldest fetishist organizations: England’s Mackintosh Society.

In her book Fetish: Fashion, Sex, and Power, Valerie Steele excerpts letters from the Mackintosh enthusiasts of the 1920s. One writer’s husband was keen on the “lovely rustling swish of rubber,” she wrote. “I could see how he enjoyed every movement I made, so you can guess that I was very happy, too, as long as I gave him so simple a pleasure.”

For fetishists, as I wrote for Vice in 2012, the preferred material has a power stronger than mere sex appeal, and a clothing item can elevate it from mere commodity into an object of hyper-sexualized worship. For some, the thrill is in wearing the garment themselves. For others, it’s in engaging with the person who wears it. For the most intense of fetishists, it doesn’t really matter who the wearer is; the power is in the object, whether a stiletto boot, tight-laced corset, or wet-shine catsuit.

The outbreak of World War II seems to have intensified rubber’s protective appeal; gas masks and gloves accessorized the photos that readers sent to London Life, along with letters that famously chronicled their fetishes between 1923 and 1940.

In the 1960s, The Avengers’ cat-suited Emma Peel and mod, glossy go-go boots paved the way for punk designers such as Vivienne Westwood and Malcolm McLaren to bring latex (and leather) fetishism into the full glare of fashion. Filmmaker John Samson captured not only McLaren and Westwood in his 1977 documentary, Dressing for Pleasure, but also caught up with the later generation of the Mackintosh Society. Grinning in their slickers in the rain, the society’s brand of fetishism seems unexpectedly well-lit and wholesome:

In 1985 Dianne Brill—Warhol muse, fashion designer, and New York’s “Queen of the Night”—stepped out regularly in rubber. (“She looks like Venus rising from the primeval slime,” offered The Official Preppy Handbook author Lisa Birnbach, at the time.)

A decade later, writer Candace Bushnell pulled on a series of latex outfits in the name of investigation for Vogue, and found herself flirtatious and brimming with confidence (however sweaty).“When I find myself telling a TV producer he should give me my own show, I decide it’s time to go home,” she wrote. Perhaps you remember her series, Sex and the City, which debuted a few years later.

It’s powerful stuff, to be sure.

Lady Gaga wore latex to meet the Queen. Anne Hathaway said her Catwoman suit for The Dark Knight Rises left her forever changed. “The suit, thoughts of my suit… It dominated my year,” the actress told Allure in 2012. That same year, refined designer Oscar de la Renta threw the fashion media for a loop when he included a red latex top and pencil skirt in his collection.

“A fetish is a story masquerading as an object,” wrote Robert Stoller in Observing the Erotic Imagination. It wasn’t so long ago that society saw those stories as threateningly subversive: In 1932, the Irish government banned London Life (pdf); some three decades later, the English government prosecuted several manufacturers of rubber and leather fetish-wear for their work.

We haven’t seen the last of fashion’s lust for latex. But getting into something as overtly sexual and widely publicized as the Pirelli Calendar marks a milestone of sorts—a stamp of approval that may signal the moment the material went mainstream.