What Martin Luther has to do with Ferguson

On Aug. 9, Darren Wilson, a white police officer, fatally shot Michael Brown, an unarmed African-American teenager, provoking weeks of protest around the country. Since the beginning, social media has been a central part of the story. The shooting gave rise to an online movement, with millions of Americans using Twitter and Facebook to respond to the events in Ferguson, Missouri, and join a growing discussion about police violence.

On Aug. 9, Darren Wilson, a white police officer, fatally shot Michael Brown, an unarmed African-American teenager, provoking weeks of protest around the country. Since the beginning, social media has been a central part of the story. The shooting gave rise to an online movement, with millions of Americans using Twitter and Facebook to respond to the events in Ferguson, Missouri, and join a growing discussion about police violence.

By the evening of Nov. 24, there had been more than 20 million social media messages containing the word “Ferguson.” Then came the announcement from St. Louis County prosecutor, Robert P. McCulloch, that the grand jury would bring no criminal charges against Wilson. The social web erupted in response, with 7.3 million messages mentioning Ferguson that day alone. (For comparison, 1.1 million tweets were sent during Barack Obama’s 2013 inauguration ceremony.)

But McCulloch’s statement brought social media into the story in another way, as well. Discussing the difficulties he experienced working on the Brown case, the prosecutor said, “The most significant challenge encountered in this investigation has been the 24-hour news cycle and its insatiable appetite for something, for anything to talk about, following closely behind with the nonstop rumors on social media.”

His frustrations are, in one respect, understandable. Given the volume and intensity of the online movement, it was inevitable that not everything shared on social media would be true. In any conversation that involves tens of millions of people, misinformation is going to spread. From McCulloch’s perspective, it must also be frustrating that these millions of people are scrutinizing his actions. From a different perspective, though, that public scrutiny and discussion is a good thing, which raises the next question.

Have Facebook and Twitter made the situation better or worse? Is this technology a good thing? Has social media afforded a new outlet for social change or just another channel to bully and gossip? Of course, the answer depends on whom you ask.

In 1524, a series of peasant revolts in Germany helped spark the Protestant Reformation. The cause? According to some among the Catholic clergy at the time, it was the recently introduced printing press and the spread of revolutionary pamphlets that the new technology enabled. If you were to ask a Catholic bishop back then whether Gutenberg’s gadget was a good thing, he would be at best skeptical. Some pundits even wrote scathing pamphlets about the scourge of easily disseminated pamphlets—the 16th century equivalent of tweeting your disapproval of Twitter. Ask Martin Luther, though, and you’d likely have gotten a different answer about the value of the printing press.

In the case of Ferguson, millions of messages have been sent over the past several months from as far afield as Indonesia and Turkey, with the greatest numbers coming from New York and California. At a granular level, these data tell an even more compelling story. (Here and elsewhere, data have been sourced using my company’s social media analysis tool uberVU.) The city of Oakland, whose 400,000 residents have a history of racial tension with police, sent more messages about Ferguson in the week following Nov. 24 (36,000) than the state of Colorado’s 5.2 million people.

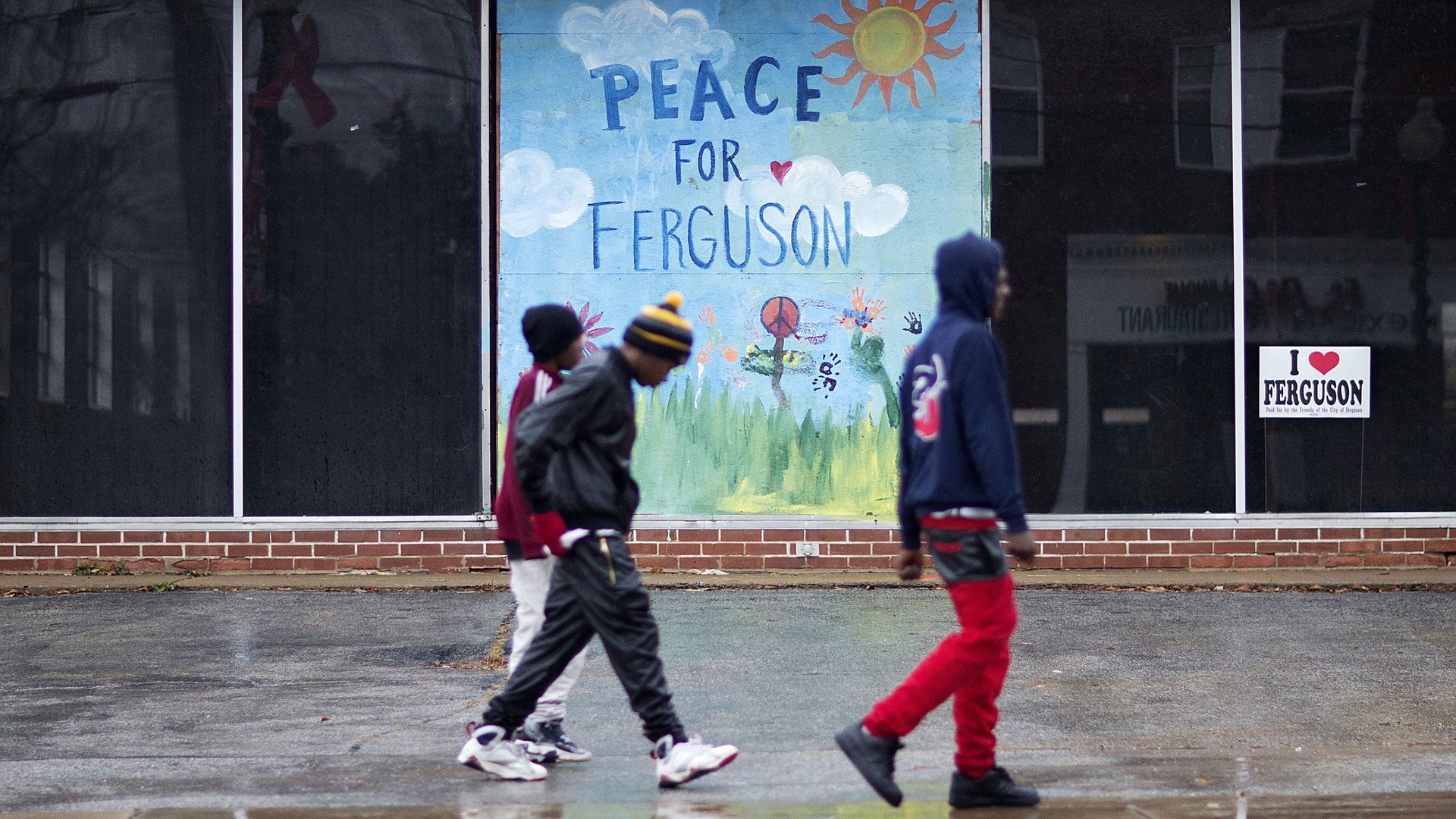

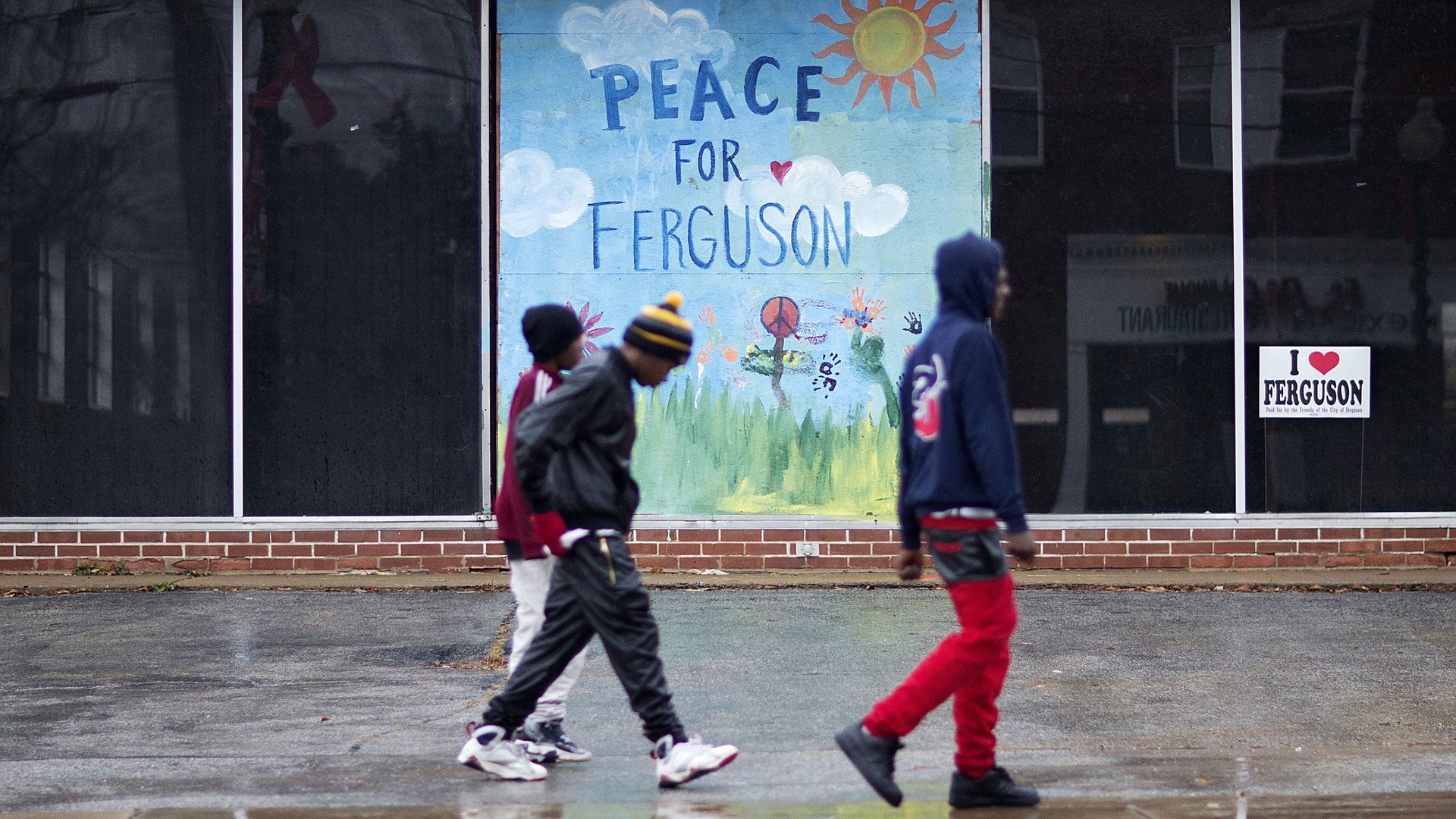

The sheer magnitude of these numbers suggests that this is anything but a case of rumor mongering. The anger Ferguson demonstrators are expressing in the streets resonates with people in communities across the US, and the world, whose members believe they have also been unfairly treated by those in power. People have taken to social media not to spread misinformation, but to give voice to real frustration that simply didn’t have a ready channel before.

The message that has increasingly appeared on protest signs, whether outside big box stores disrupting Black Friday shopping in Missouri or blocking an interstate in Washington, DC, is one of solidarity with Ferguson. We’ve seen time and time again that solidarity is one thing social media makes easier to spread. Whether that’s a good thing or not depends on which side of history you’re on.