Campus rape: A guide to the debate that’s roiling American universities

A recent article in Rolling Stone magazine detailed a brutal gang rape at the University of Virginia. It was a classic tale of sexual assault at American campuses: hard-partying, binge-drinking fraternity members, a stigmatized female victim, and an indifferent university administration.

A recent article in Rolling Stone magazine detailed a brutal gang rape at the University of Virginia. It was a classic tale of sexual assault at American campuses: hard-partying, binge-drinking fraternity members, a stigmatized female victim, and an indifferent university administration.

The piece rocked the university. The administration apologized to the victim, asked the police to investigate the case, and suspended activities at its more than 60 fraternal organizations.

But then questions arose about Rolling Stone’s reporting. After a series of fact-checking articles, statements, and updates from the magazine itself, it turned out that some of the facts were uncorroborated, undermining the story, the magazine, the reporter, and for some, the credibility of the subject, identified only as “Jackie.” Worse, many people worried it would undermine the nationwide campaign to fight campus rape. “If this story does turn out to be largely false, it will do real damage to the important new movement to crack down on sexual assault on college campuses,” wrote Margaret Talbot at The New Yorker.

This “important new movement” came about at least in part thanks to the internet, as survivors of sexual assault began to band together through social media to expose how universities across the country were letting their attackers go unpunished. It has sparked college and government investigations and galvanized public debate. These are the results so far—and the reason why people are worried about the damage the Rolling Stone article could do.

Sexual assault is pervasive, and the investigations are snowballing

In 2007, a federally funded survey of US college students (pdf) was published, based on data collected in 2005 at two large public universities. It found that about 19% of female and 6% of male students at those universities had experienced “completed or attempted sexual assault” since entering college. (Most of the available follow-up data refer to women survivors, so in this article we will be talking about women, unless otherwise specified.)

But it’s difficult to get accurate estimates. A report this month (pdf) from the US Department of Justice sums up nationwide data from 1995-2013 from the National Crime Victimization Survey, which collects data on both reported and unreported crimes. Those data say that only 0.6% of female college students have experienced rape or sexual assault. (Here is a good explanation of the differences between the two studies.) But the report also found that most survivors of sexual assault don’t seek help or report it to police, which is one reason for the unreliable numbers.

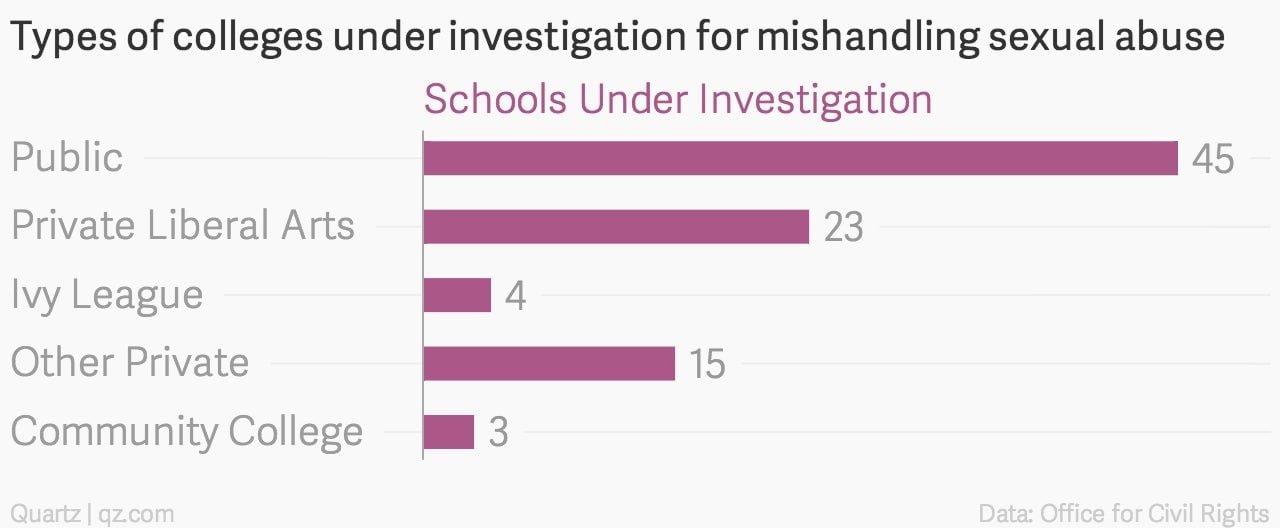

In May of this year, the US Department of Education announced it was investigating 55 colleges for mishandling complaints of sexual violence. The news set off a wave of national media stories and school responses. By Dec. 8, the number of institutions under investigation had risen to 90, according to an email the Department of Education’s Office for Civil Rights sent to Quartz. (The full list of colleges is at the end of this story.)

The list shows that campus rape happens at a wide range of schools. The University of Virginia is a large public research school. Other widely covered cases included Ivy League universities such as Columbia, in New York, where a student made the news by carrying carrying a mattress around campus, a stand-in for the dormitory bed on which she was raped. At Harvard University, an anonymous student wrote to The Harvard Crimson that she was “exhausted” by living in the same dormitory as her assailant, despite repeated efforts to have the administration move him elsewhere. Activists at small liberal-arts schools such as Occidental and Swarthmore have also filed complaints with the Department of Education.

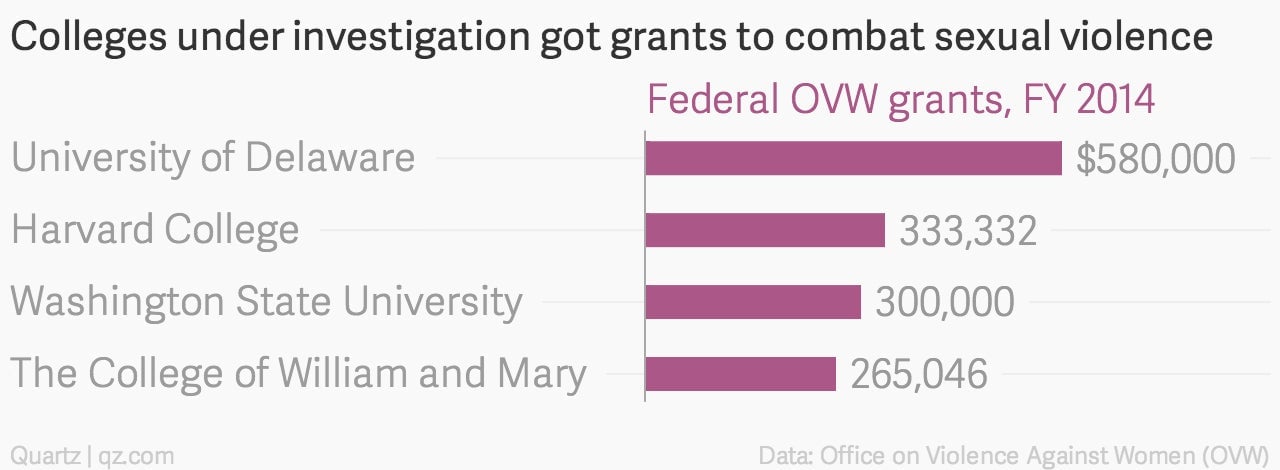

News site FiveThirtyEight found in November that 24 of the then 86 colleges under investigation had received federal funding to address and prevent sexual violence on campus, according to Department of Education data, including some in the past fiscal year:

The number of complaints is going up too

A college that fails to deal with sexual assault on campus falls foul of Title IX of the Education Amendments of 1972, which “prohibits discrimination on the basis of sex in all education programs or activities that receive federal financial assistance,” as the May press release puts it. The government has prodded universities about their obligations once a decade or so since the 1990s, and most recently (before this year’s May announcement) in 2011, when it sent a strongly worded letter to colleges and school districts.

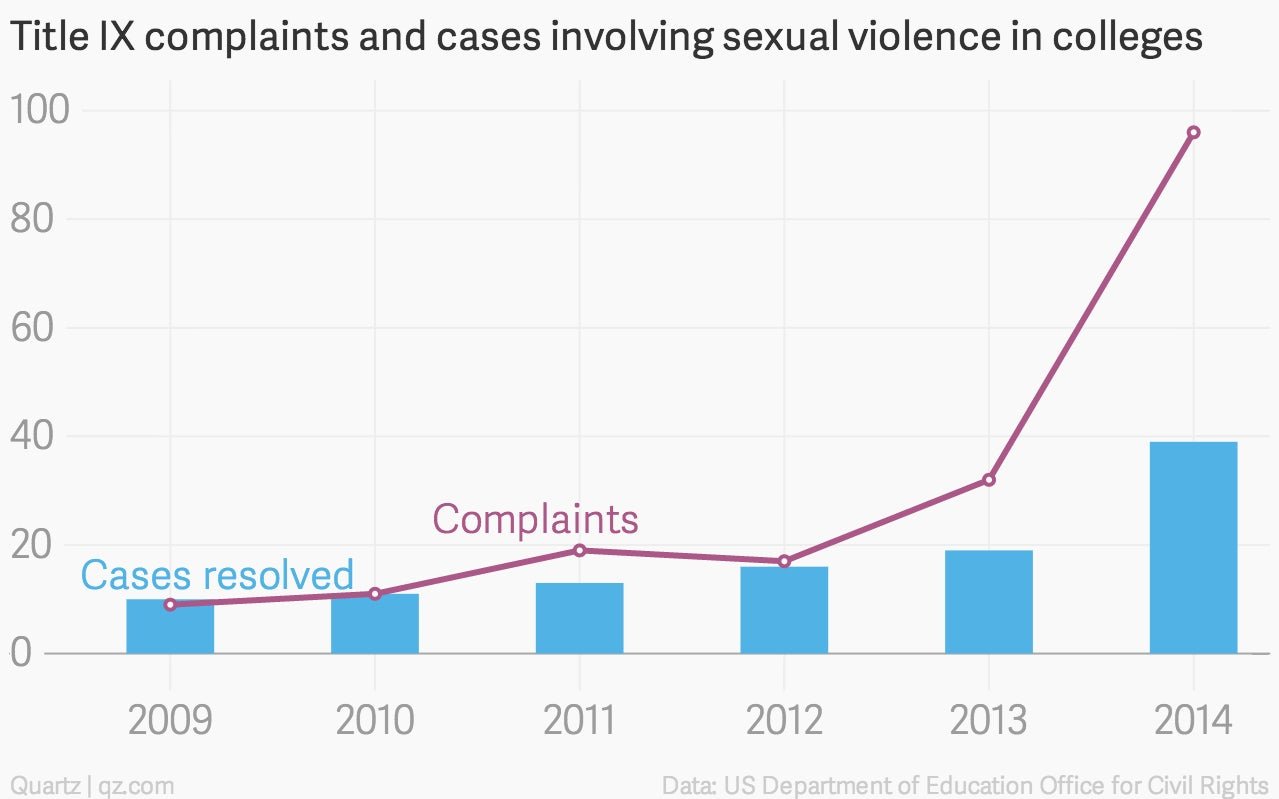

The Office for Civil Rights responds to complaints, and can also launch investigations or compliance reviews with universities if it suspects wrongdoing. Most of the cases come from complaints—since 2009, the office has initiated 18 proactive investigations. In a sign that more people are coming forward, the number of complaints received jumped from nine in fiscal year 2009 to 96 in 2014, and the number of sexual assault cases resolved rose from 10 in 2009 to 39 in 2014, according to data the office provided to Quartz.

America’s legal age for drinking plays a controversial role

College rape isn’t just an American phenomenon, of course. But much of the discussion in the US focuses on two very American issues: the role of fraternities—the male-only college societies whose members live and often socialize together—and underage drinking.

With the legal drinking age set at 21, many students drink at fraternities or other student housing. According to several studies, fraternity members are three times more likely to commit rape than other college men. In October, a chapter of the Phi Delta Theta fraternity at Texas Tech University was stripped of its charter for displaying a banner emblazoned with “No Means Yes, Yes Means Anal.”

Alcohol is a big factor in sexual assault by fraternity members. According to the 2007 study, almost 60% of all completed sexual assaults on women occurred when the victim was incapacitated by drugs or alcohol. Fraternity members were twice as likely to be involved in the drug-and-alcohol cases as in cases when the victim was physically coerced.

In light of the Virginia revelations, many have called for stricter alcohol regulations on campus. Wayne Curtis at Politico magazine, however, suggests the opposite: “By lowering the drinking age, it’s possible to coax the party out of the demimonde and into a better-lit public realm.” Drinking in a more public place, such as a bar, “instantly raises the threshold of getting away with misbehavior.”

Doubt and stigma dissuade women from reporting rape

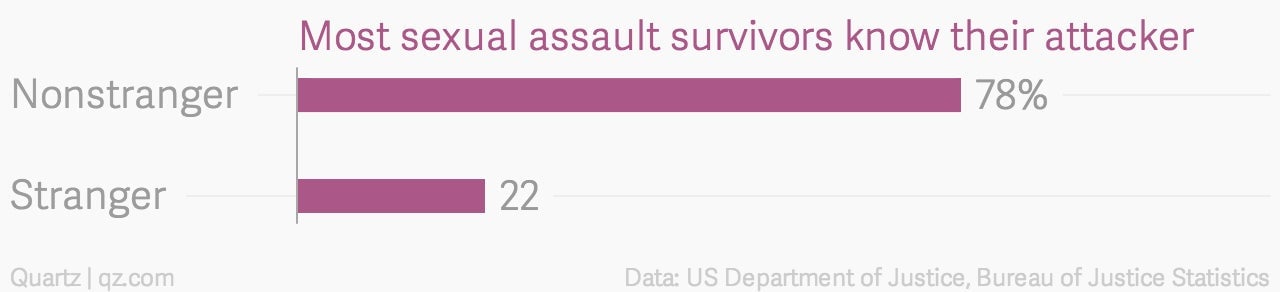

Women are often blamed for when they are sexually assaulted—for drinking too much, for wearing “provocative” outfits, for supposedly putting themselves in a position to be attacked. Most rape victims know their attackers, which further complicates the perception of whether or not it was rape.

That means female rape victims, like Rolling Stone’s “Jackie,” are often doubted. But the most reliable research available suggests that only between 2% and 8% of people lie to law enforcement (pdf) about being sexually attacked—that includes reports from men and women around the world.

Of the women who chose not to report a sexual assault to the police, according to the 2007 study, here are some reasons why:

Close to 40% thought it was unclear that there was a crime, or that harm was intended.

Statistics are hard to get…

A federal law—The Clery Act—requires schools to report crimes, including sexual assault, but those statistics are often incomplete. Because sexual violence is such a large campus problem, many colleges have their own criteria and processes for addressing it.

What’s more, on some campuses the definitions for different forms of sexual violence—harassment, assault, battery, rape—are different from the state’s terminology, as are the legal standards. And many US states define rape and sexual assault differently. This confusion, along with a whole host of other concerns, can discourage a survivor from reporting a case.

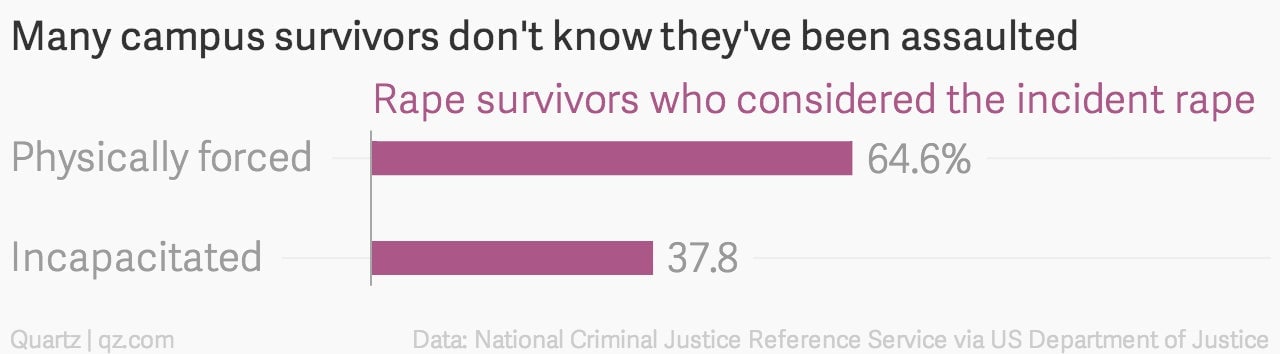

The 2007 survey also found that many women who described being raped did not recognize it as rape—especially when drugs or alcohol were involved. (The study defined rape as “sexual assault that entailed oral, vaginal, or anal penetration.”)

Then there’s the question of to whom a student should report an assault. In the 2007 study only 12.9% of female students who had been sexually assaulted through physical force reported the incident to police or campus security, and a mere 2.1% of those who had been incapacitated—presumably in part because they feared consequences for drug use or underage drinking.

In fact, sexual assault is so underreported that colleges that see increases in reported sexual assaults tout that as a good thing: It doesn’t mean there’s more assault, it means more people are coming forward.

…and enforcement is hard to pursue

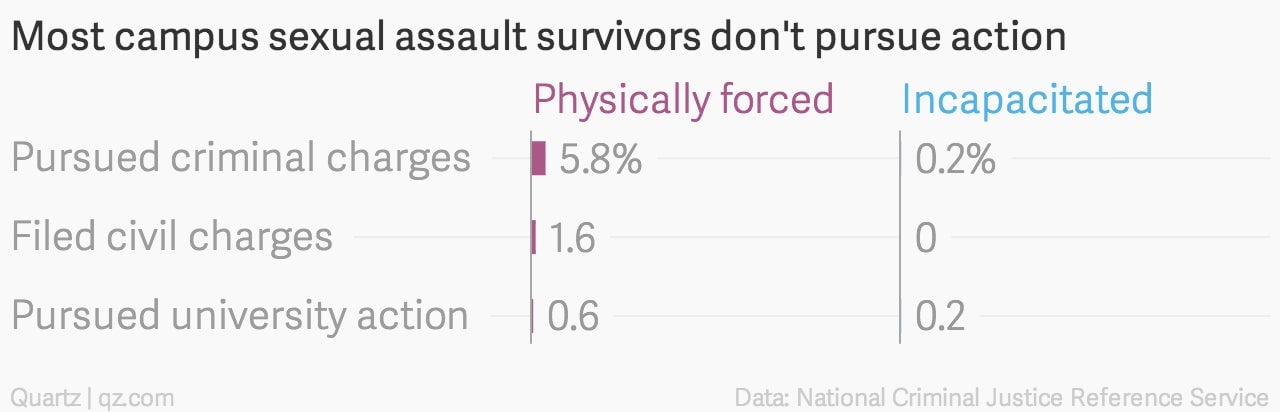

Finally, even if they reported the crime, few in the 2007 survey pursued action:

The recent report on the National Crime Victimization Survey says that women students aged 18-24 are less likely to be raped that non-students—but it also found that if they are, they’re less likely to report it to the police. Prosecutors pursue few charges of sexual assault, and even when they do, it can take weeks or months before they order an arrest, during which time the victim may be seeing her attacker daily on campus. Those factors can deter victims from turning to the authorities.

They can instead turn to the college, which can suspend or expel an attacker on less stringent evidence than a court. As a result, colleges have had to develop their own quasi-judicial systems. These too have come in for criticism, since many schools don’t have the resources or training to conduct criminal investigations.

This situation also leads to rules policing sexual behavior that can be hard to parse. California recently became the first state to pass a law requiring affirmative consent for sex on college campuses that receive state financial aid. That means that when a student claims that she has been sexually assaulted, the college must find the alleged attacker guilty if the victim did not actively say “yes” or give “affirmative, conscious, and voluntary agreement to engage in sexual activity.” That, though, only covers punishment by the college. To press criminal charges, the survivor must still go to the police, and endure the lengthy legal process.

Full list of US colleges under investigation for Title IX violations in regards to handling sexual violence cases as of Dec. 8, 2014 (Southern Methodist University is on this list, but the Department of Education announced on Dec. 11 that they had resolved three cases with SMU):