Netflix makes the case that ratings ruined TV

Ted Sarandos has one of the coolest jobs in America.

Ted Sarandos has one of the coolest jobs in America.

The executive in charge of Netflix’s multibillion-dollar content budget gave a presentation to investors in New York today at a conference hosted by UBS. It was standing-room only, which speaks to Netflix’s growing stature in the investment community and Sarandos’ growing profile in the broader media industry. And he offered plenty of fascinating tidbits for attendees to chew on.

Perhaps the most interesting of those was on the topic of TV ratings. The Wall Street Journal (paywall) recently reported that Nielsen (which is facing a crisis of confidence over its ratings methodology) will soon start measuring how many people are watching shows on internet services such as Netflix and Amazon Prime. Some observers think this will be a problem for Neftlix, since competitors for both content and eyeballs would finally know how many people are actually watching its shows.

But Netflix sells subscriptions, not advertising, and Sarandos rejected that thinking out of hand. Ratings are “an irrelevant measure of success for us. We don’t sell advertising, Nielsen ratings are all about justifying the cost of advertising…I honestly think it works against the quality of television.”

He pointed to Seinfeld, a beloved show today, but which was not actually not a hit for four seasons. “The first couple of episodes of every show are clunky,” he said. “Look how many shows don’t get past the third episode. The ratings discussion has been very negative” for the quality of TV.

World domination

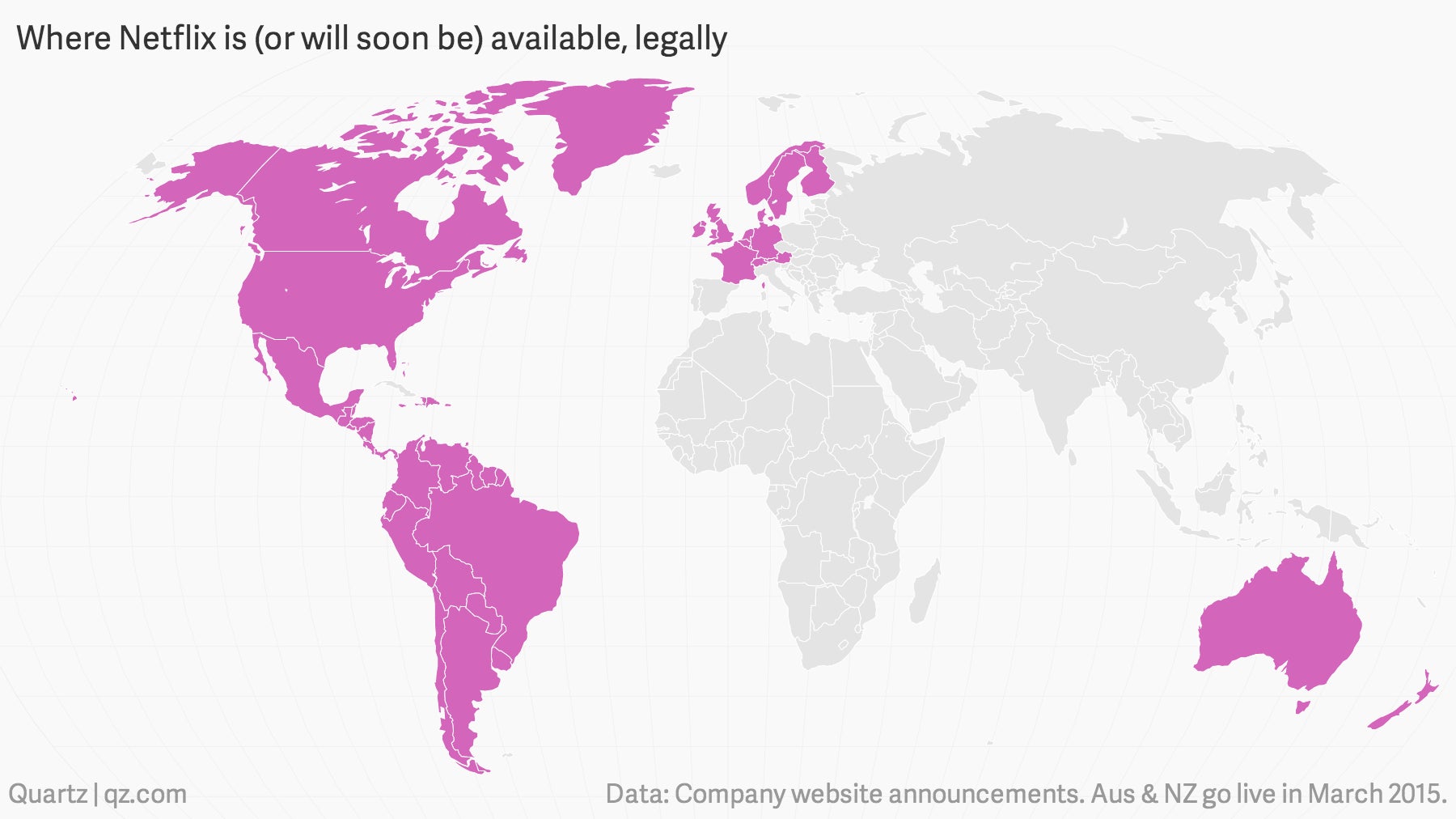

Netflix recently announced plans to enter Australia and New Zealand. It already has a strong presence in northern Europe and Latin America, but vast swathes of the planet remain untouched by its footprint—for now. ”Within five years we would like to see the product completely global,” Sarandos declared.

How does it plan to do that? In part through original content. Sarandos says the company has a long-term goal of rolling out 20 new series (or new seasons of existing series) each year, which works out to about one every 2.5 weeks.

But these won’t necessarily be big bets that appeal to everyone. Rather, it is about developing shows that really appeal to certain audiences. The company uses its proprietary data to identify what might appeal to certain audiences, and then sizes its financial commitment appropriately based on the size of those audiences. Some of its shows (like Lilyhammer) have niche appeal, others (House of Cards, Orange is the New Black) are more mainstream.

Sarandos is not concerned about having to order these shows from big Hollywood studios, which are increasingly competing against Netflix with their own on-demand offerings. The studios already compete with each other, and sell to each other, he explained, citing the example of Modern Family which is made by Fox but airs on ABC.

Netflix has “emerged as the first global buyer of programming,” he explained, which can be good for studios in some cases, because it can help them cover costs more quickly.