How Wall Street lobbyists are using shutdown fears to push risk (and rewards) back to banks

The momentum behind a $1.1 trillion spending bill designed to avert a US government shutdown appears inexorable—excellent news for Wall Street, which is counting on the legislation to help it roll back some of the more restrictive regulations imposed after the 2008 financial crisis.

The momentum behind a $1.1 trillion spending bill designed to avert a US government shutdown appears inexorable—excellent news for Wall Street, which is counting on the legislation to help it roll back some of the more restrictive regulations imposed after the 2008 financial crisis.

The rules in question refer to swaps, derivatives contracts in which the parties essentially exchange financial assets for a set amount of time. The Dodd-Frank financial reform bill of 2010 included regulations designed to prevent the cascading effects of derivatives calls like the ones that threatened to spread insolvency through the financial system in 2008, and to reduce the risk that taxpayer funds would be put toward bank bailouts in the future.

The big financial firms that dominant the swaps markets were particularly unhappy with rules preventing them from holding or trading derivatives within their federally insured bank subsidiaries—where they typically have an advantage. (That’s because the prospect of government bailouts arguably affords the bank subsidiaries higher credit ratings, which comes in handy when you’re playing in the swaps market.)

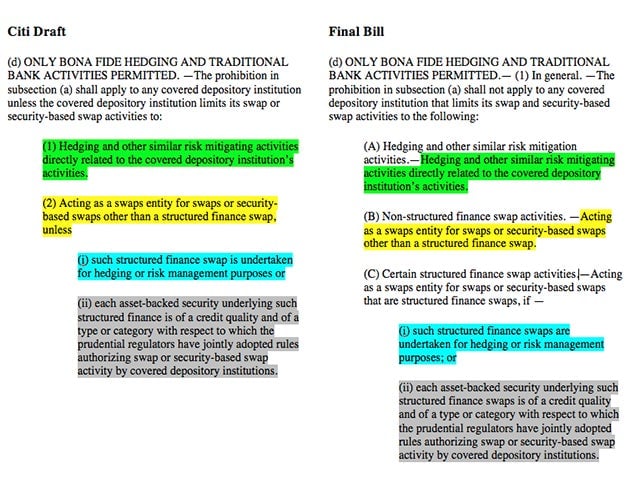

Facing the prospect of having their derivatives activities “pushed out” to subsidiaries unprotected by federal deposit insurance, the big banks pushed back. During the drafting of Dodd-Frank, they succeeded in keeping some categories of swaps in house, including foreign exchange, gold, silver, and interest rate swaps. But the banks earned a bigger victory in 2013 by getting the Republican-controlled House of Representatives to pass a bill essentially written by Citigroup lobbyists to create large exemptions in the rule.

It turns out the same language was slipped into the current spending bill; here’s a helpful graphic from Mother Jones:

The provisions would likely allow the banks to pursue many different (and potentially high-risk) financial activities under the guise of “hedging”—remember, JPMorgan’s Chase’s $6 billion in London Whale losses were ascribed to a hedge.

Democratic leaders are upset about the provision, which they say represents a give-away to financial interests—the largest banks, JPMorgan, Citi, Bank of America, Wells Fargo, and Goldman Sachs conduct the most derivatives business—but it will be interesting to see if it leads to real obstruction to the bill; no one wants to be seen as the cause of a government shutdown.

The vote counting will be tricky: House speaker John Boehner will likely need some Democratic votes to pass the spending bill before it goes to the Senate, but he may not get them if the Democratic leadership decides to fight back against the swaps provision. Even it passes the House, the Senate may find a way to remove the provision without derailing the deal, but each hour closer to the deadline makes delay more politically risky.

In any case, the Democrats don’t have much room to maneuver here: Like Republicans, they salt the membership of Congressional financial oversight committees with members who need to raise money—the committee appointments make these lawmakers pretty irresistible to donors from the financial sector. That’s one reason the bill containing these exemptions on swaps, the one that passed last year in the House, attracted 70 votes from Democrats. It’s a picture of policymaking in the world of pay-to-play politics that the proposed spending bill is only reinforcing.