What the UK’s former ambassador to Cuba thinks about Obama’s reset

The resetting of US-Cuba relations has been a long time in the making, but without the Alan Gross case it is likely it would have happened sooner. I think both sides have thought long and hard about what makes sense and, with Obama no longer having to run in an election, he has seized the opportunity. He, secretary Kerry, and before him secretary Clinton, had long recognized that the legalistic nature of US Cuba policy, as framed in the long-standing embargo legislation, was counterproductive to US interests.

The resetting of US-Cuba relations has been a long time in the making, but without the Alan Gross case it is likely it would have happened sooner. I think both sides have thought long and hard about what makes sense and, with Obama no longer having to run in an election, he has seized the opportunity. He, secretary Kerry, and before him secretary Clinton, had long recognized that the legalistic nature of US Cuba policy, as framed in the long-standing embargo legislation, was counterproductive to US interests.

Why has it happened now? Obviously the short answer is that there has been a deal to release Mr Gross and a US agent in jail in Cuba, alongside the Cubans held in the US for setting up a spy network in the US. But there are wider reasons. The Cuban American community is increasingly reconnecting with their families and with small businesses being set up on the island. They want restrictions removed on ways they can interact, for example on the use of US credit cards, banking services and the ability to supply US communications equipment. President Obama has long been conscious of these wishes and his measures today show he is making the engagement between Cuban Americans and those on the island easier.

On the Cuban side, there are also clear reasons why the time is right to try something different. Raul Castro has committed himself to step down from the presidency in 2018 so if there are to be major changes in the relations with the US or more ambitious economic reforms than have been implemented so far, he knows that only he, as a Castro, has the authority to do that. And in his quest for hard currency he sees an increasingly weakened and unstable ally in Venezuela wounded by sinking oil prices, and other partners like Iran and Russia also enduring economic downturns. So he sees the US as the most immediate possible new source of hard currency. He also wants to show the Cuban people that he is pragmatic and that the reform process is real, and will not, unlike on many previous occasions, be reversed. Reframing US relations is part of this process.

What happens next

What will be the results? It’s too early to say, but the two sides do know each other’s positions well so some outcomes may be possible in the near term. The first target will be to establish full embassies. The US and Cuba each has large diplomatic offices, called Interest Sections, in Havana and Washington DC respectively so that this move, though very important symbolically, has a strong basis already for implementation.

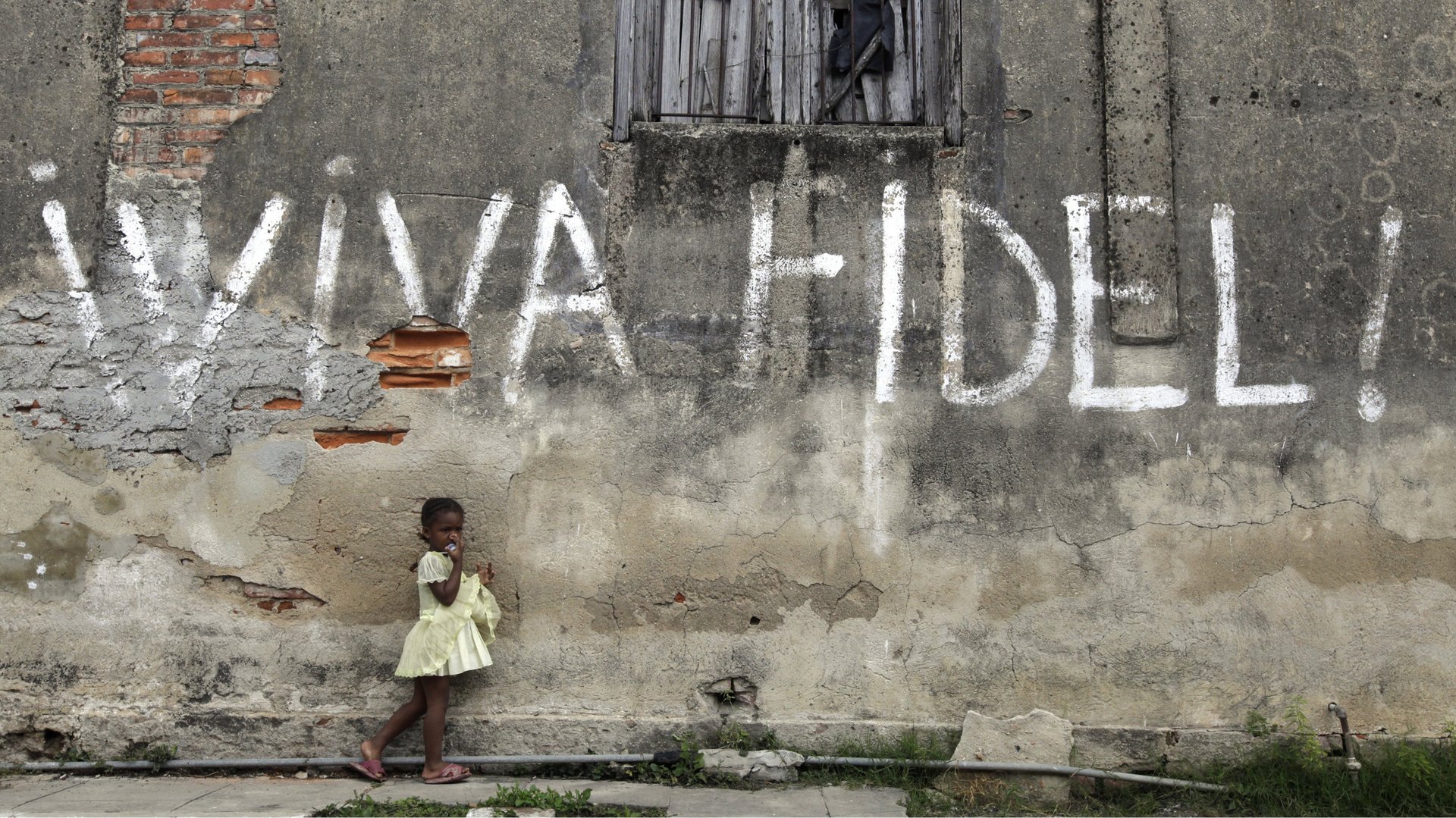

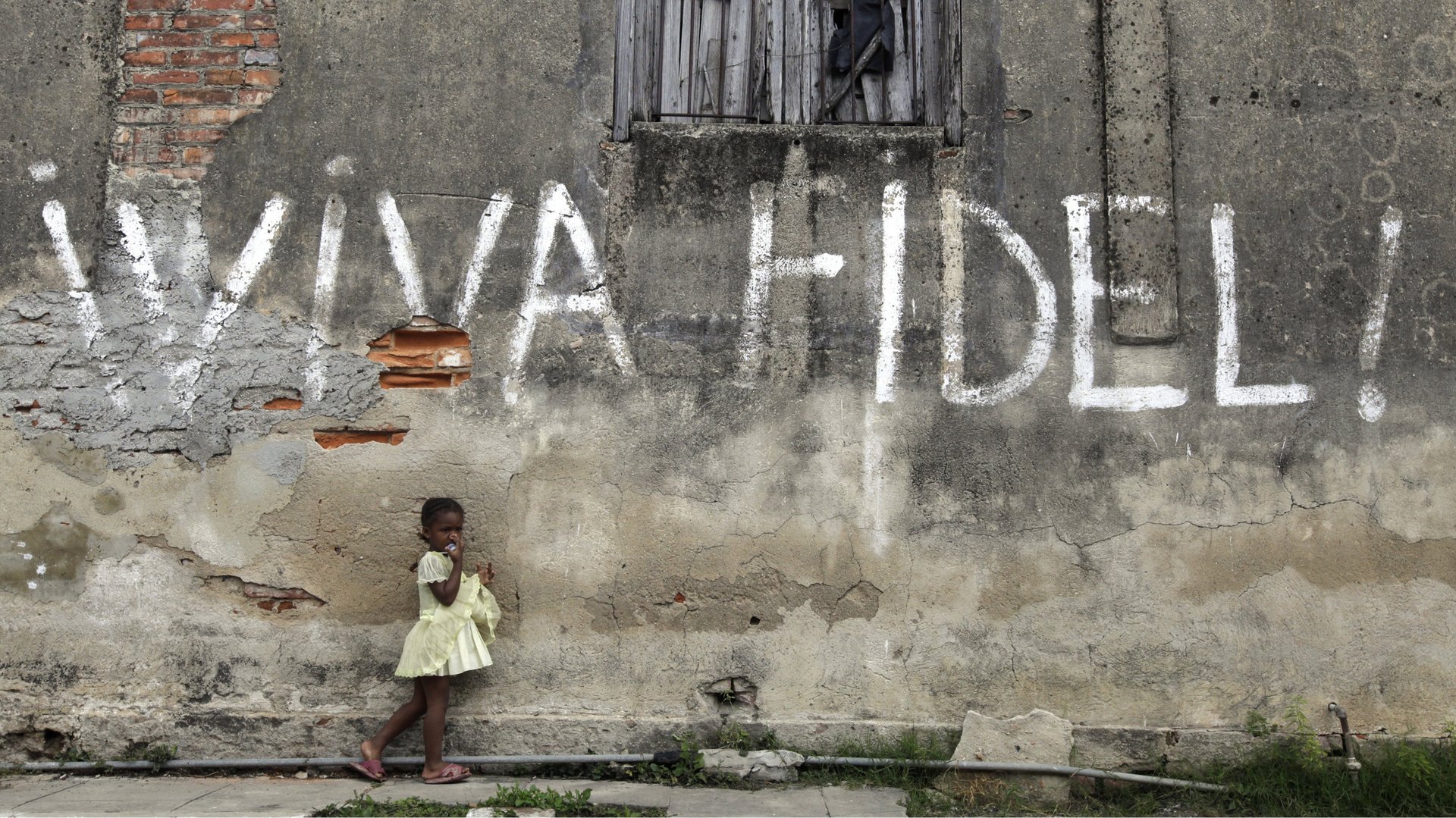

I think some members of Congress will certainly try to argue this is a US conciliation and the Cuban government has made no fundamental reforms to deserve this degree of recognition. President Obama has argued that the existing five decade-old policy has been a failure. The totalitarian nature of the Cuban regime remains and ordinary Cubans have been deprived of an economy where their own efforts can lead to better living standards. There will however be noisy debates over whether now is the right time or and whether full diplomatic relations are a unwarranted ‘reward’ for Cuba which still represses the opposition, has no independent media, and has restrictive controls over use of the Internet,

US policy objectives towards Cuba have therefore changed—they no longer see the removal of the existing regime as achievable or a policy that makes diplomatic sense. What the new approach means is that the US wants to be fully on the diplomatic field. It wants to be able to make plays that might influence the future of Cuba and to enable ordinary Cubans to participate fully in determining their own future. So engagement is designed to promote reforms in Cuba in the economy which will loosen controls that Cuba has imposed in other areas.

The majority of US opinion wishes to open a new chapter with Cuba. They resent their travel rights being restricted and view the prospects of business openings, and new infrastructure projects in an economy which has been held back for decades as alluring. They believe that openings in Cuba will be driven from the bottom-up and Cubans will create their own network of relations with their government less and less involved. They will in turn pay taxes to the government who will need to facilitate their economic activities rather than stand in their way.

The next steps might not be so easy

Nevertheless, all will not change overnight. There are many legacy issues that remain—the existence of the US base at Guantanamo Bay, the claims of US citizens and companies for property nationalized in 1960 and later, and the provisions of the key pieces of US legislation, such as the requirement in the Helms Burton Act that non official US assistance can be given to Cuba while either Fidel or Raul Castro form part of the government.

We are unlikely to see a relaxation of all Cuban anti-US rhetoric for some time as long as any restrictions on US trade and investment remain, and the US continues to put human rights pressure on Cuba. And all foreign investment in Cuba remains heavily controlled. The Castros fought the revolution partly to free Cuba from US dominance in the economy so we are unlikely to see big US projects approved any time soon.

There have been false dawns before and even this time a major event might derail the process—for instance, if there were a major crackdown on the opposition, the independent bloggers, or if the small businesses were closed. But both sides have carefully considered what the alternatives are and have decided that a new course and new chapter are worth a try.