Scientists can now explain why the first half of the 20th century was so cool

Chemical clues in skeletons produced by coral growing at Kiribati contain a newly discovered warning. They caution of a global climate system that’s capable of drawing decades’ worth of hoarded heat out of the Pacific Ocean, and belching it back into the atmosphere.

Chemical clues in skeletons produced by coral growing at Kiribati contain a newly discovered warning. They caution of a global climate system that’s capable of drawing decades’ worth of hoarded heat out of the Pacific Ocean, and belching it back into the atmosphere.

A cryptic chemical weather log kept by Tarawa Atoll’s stony coral in the tropical Pacific archipelago has been cracked, helping scientists explain a century of peaks and troughs in global warming—and inflaming fears that a speedup will follow the recent slowdown.

Added to a growing body of research, the newly published findings indicate that all it would take to trigger what could be an historically unparalleled period of rising global temperatures would be a shift in the winds. And that type of change in the intensity of Pacific trade winds appears to happen every 20 to 30 years or so.

The coral-based findings, published Dec. 22 in Nature Geoscience, provide new historical data supporting previous modeling results and observations that point to the long-term waxing and waning pattern of the trade winds in affecting worldwide temperatures.

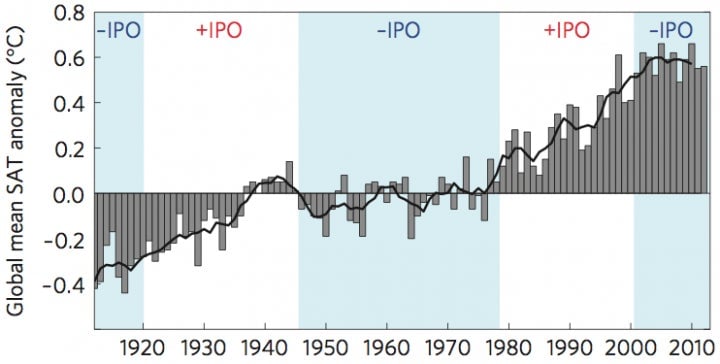

For the past few decades, the Interdecadal Pacific Oscillation, as the influential cycle is known, has been in what’s called a negative phase, meaning trades winds have been strong.

The growing body of scientific evidence indicates that this negative phase has played a heavy role in driving an approximately 15-year old slowdown in worldwide surface warming. It suggests that a speedup in warming may follow the next switch to the oscillation’s positive phase, when trade winds weaken, and the effects of the natural cycle exacerbate those of unnaturally increasing levels of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere.

Diane Thompson, a postdoctoral fellow at the National Center for Atmospheric Research who led the study, said we’re in a surface warming slowdown right now because the Pacific trade winds are strong. But she says that apparent bout of good fortune won’t last forever.

“When winds weaken, which they inevitably will, warming will once again accelerate,” Thompson said. “The warming caused by greenhouse gases and the warming associated with this natural cycle will compound one another.”

Strong tropical Pacific trade winds serve as an air conditioner for the world, scientists are concluding. They mix warm equatorial surface water into greater depths, and help bring cooler waters to the surface. But, like the window-mounted AC unit that cools your living room during summer, all the while heating the air outside, the strong winds aren’t cooling the planet. They’re just moving heat-wielding energy to where it will bother us less.

And, just like that window-mounted unit, the strong trade winds will eventually break down. When the global air conditioner breaks down, modeling and past experience suggest that the process will start to operate in reverse.

In February, Australian and American researchers who compared ocean and climate modeling results with weather observations published findings in Nature Climate Change advancing earlier studies that explored the oscillation’s global influence. They found that the effects of strong Pacific trade winds during the past two decades were “sufficient to account” for the recent slowdown in global warming.

The slowdown refers to slower-than-expected rates at which temperatures measured on the land and at sea surfaces have been rising since the turn of the century. The amount of energy being trapped on Earth continues to rise at a quickening pace, because of the effects of the thickening cloud of greenhouse gas pollution in the atmosphere, but more of that energy than usual has been ending up in the oceans. That ocean heat—while hard for many of us to notice directly—has been driving record-breaking global temperatures, with 2014 on track to be the hottest on record, and to more vicious tropical storms.

The Australian and American researchers drew a similar comparison in their paper between strong trade winds and a slight cooling in global surface temperatures from 1940 to the 1970s.

On Dec. 22, a team of American and British scientists led by Thompson reported on their chemical analysis of a sample core bored out of coral on the most populated atoll of Kiribati, a postcard-worthy Pacific Ocean country comprising many small islands. The sample was selected for the coral’s location, growing just outside the mouth of a west-facing lagoon.

The scientists measured changes over time in the amount of manganese in the skeletons produced by coral growing since the 1890s. The waters inside the lagoon are sheltered by a ring of land from the trade winds, which blow from the east. When trade winds are weak, the lagoon’s waters are churned more frequently by gusts blowing from the west. When those gusts blow in, they kick up sediment in the lagoon, releasing manganese into the water that corals can use in place of calcium to grow their skeletons.

The team also measured strontium in a coral sample taken from Jarvis Island, an uninhabited speck of land southwest of Kiribati, to gauge historical surface water temperatures. Strontium levels in coral skeletons are affected by ocean temperatures.

The scientists found that winds blowing a century ago had a similar relationship with global weather as the more recent links that have been discovered by other scientists.

“We know that winds flip-flop between periods of strong trade winds and periods of weak trade winds,” Thompson said. “Our study shows that these winds play a role in the rate of global temperature rise.”

Thompson’s team found evidence in its Kiribati coral core of weak trade winds early in the 20th century. Those winds coincided with a period, from 1910 to 1940, when global temperatures rose faster than could have been caused by greenhouse gas pollution alone, given the still-nascent state of mass industrialization.

The group also found evidence that trade winds were stronger and surface temperatures were cooler from 1940 to 1970, providing additional evidence of the relationship between the Pacific trade winds and the rates at which global temperatures have been changing.

“The paper confirms the idea that tropical Pacific trade winds play a major role in global climate variability,” Matthew England, a professor at the University of New South Wales who was not involved with the coral study, said. He said its findings support those from other recent studies, including February’s Nature Climate Change paper, which was published by a team that England led.

“What’s very much new here is the attribution of the early 20th century warming to weakened Pacific trade winds,” England said.

The use of coral cores in the study was praised by Braddock Linsley, a professor at the Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory of Columbia University who studies ancient climatic conditions by analyzing coral skeleton samples. He was not involved with the study.

Linsley said the new results were “exciting,” suggesting that the “poorly understood, rapid rise” in surface temperature from 1910 to 1940 was, in part, “related to changes in trade wind strength and heat release from the upper water column” of the Pacific Ocean.

“The mounting evidence is coalescing around the idea that decades of stronger trade winds coincide with decades of stalls or even slight cooling of global surface temperatures, as heat is apparently transferred from the atmosphere into the upper ocean,” Linsley said.

Winds over the Atlantic Ocean also appear to modulate global surface temperatures, albeit to a lesser extent than those over the Pacific Ocean. The science isn’t settled on just how much those Atlantic winds, and other potential forces, have contributed to the heaving nature of global warming. “We’re still at the beginning” of this field of research, Stefan Brönnimann, a University of Bern professor who investigates climate variability, said. He also wrote a ‘news and views’ article for Nature Geoscience assessing and describing the new research. “Pacific and Atlantic influences are not mutually exclusive.”

The new study’s findings were limited by the fact that just one coral core was analyzed to serve as a proxy wind gauge—a shortcoming that the researchers aim to address. “Measurements of manganese in coral skeletons are difficult and time consuming,” Thompson said. “Now that we know how important they can be, we will be making more.”

Evidence of rising temperatures deep in the Pacific Ocean, even as surface temperature rise has slowed, has come in part from measurements of the rise of expanding seas. As global temperatures continue to increase, the hastening rise of those seas as glaciers and ice sheets melt threatens the very existence of the small island nation, Kiribati, whose corals offered up these vital clues from the warming past—and of an even hotter future, shortly after the next change in the winds.

This post originally appeared at Climate Central.