Our favorite economics paper of 2014 has four authors with the same surname

For an economics paper, it is mercifully short. Written by Goodman, Goodman, Goodman, and Goodman (hereafter Goodman et al), the paper “is the first coauthored by four non-related surname-sharing economists,” write the authors in “A Few Goodmen: Surname-Sharing Economist Coauthors,” which will be presented at the upcoming annual meeting of the American Economic Association (AEA). ”Our main contribution is showing that such a collaboration is feasible.”

For an economics paper, it is mercifully short. Written by Goodman, Goodman, Goodman, and Goodman (hereafter Goodman et al), the paper “is the first coauthored by four non-related surname-sharing economists,” write the authors in “A Few Goodmen: Surname-Sharing Economist Coauthors,” which will be presented at the upcoming annual meeting of the American Economic Association (AEA). ”Our main contribution is showing that such a collaboration is feasible.”

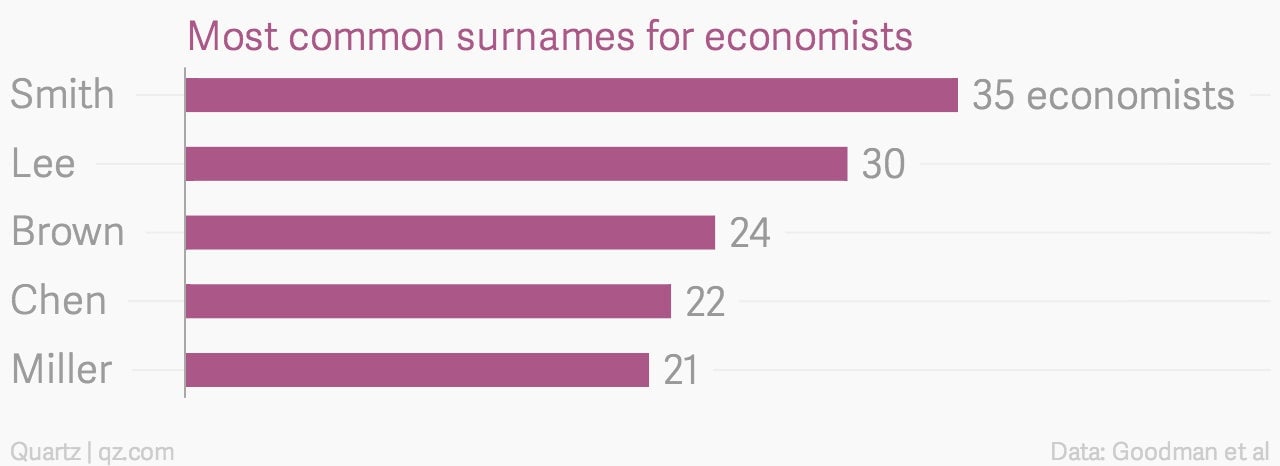

The authors interrogated data from five economics journals running from 1970 to 2012, identifying “nearly 9,000 unique economists, of whom 45% share a surname with at least one other economist in the data. Within that group, 43% share a surname with only one other economist, 17% share a surname with two other economists, and 10% share a surname with more than 10 other economists.”

Using the methodology of “introspection, asking around, and scanning www.econjobrumors.com threads concerning ‘famous couples’,” the authors found four types of relationships that lead to surname sharing coauthors. These include married economists, whose output includes classics such as Romer and Romer (2013) on monetary policy, Reinhart and Reinhart (2010) on macroeconomic crises, Summers and Summers (1989) on financial markets, Ostrom and Ostrom (1999) on public goods, Ramey and Ramey (2010) on parental time allocation, Ellison and Ellison (2009) on internet-based price elasticities and Friedman and Friedman (1990) on personal choice.

The second type of surname sharers are siblings. “Kehoe and Kehoe (1995) on general equilibrium models, Dal Bo and Dal Bo (2011) on social conflict” are good examples—though the Goodmen note a dearth of sister co-authors, “pointing to a substantial gap in the literature.”

Other types are rarer. The authors found only three parent-child coauthors, including a three-author paper by Tremblay, Tremblay, and Tremblay (2011), “written by two parents and their son studying a Cournot-Bertrand model of competition.” Only one grandparent-grandchild pair was found, Modigliani and Modigliani (1997) on risk-adjusted performance.

Finally, unrelated individuals on the same campus: Only two of these were unearthed.

A shaky argument

The study of namesake coauthors by Goodman et al makes a significant contribution to the field of namesake coauthors, being the first to be written by four namesake coauthors—or so they claim. Some might not be convinced by their argument:

The one example we have uncovered of a published economics paper with four surname-sharing coauthors is Skarbek, Skarbek, Skarbek, and Skarbek (2012), written by two brothers and their two wives. We argue, however, that this research does not diminish our contribution, for two reasons. First, though David and Emily Skarbek are husband and wife economists, Brian and Erin Skarbek are husband and wife attorneys. As such, the paper has only two economist coauthors. Second, when that research project began, both women still had their maiden names. The fourway name-sharing arose only because of two marriages and the resulting name changes that occurred during a lengthy publication process. We therefore suspect that the shared surnames may be endogenous to the publication process itself.

Goodman et al bolster their defense arguing that in any case, the fact that they are unrelated makes their contribution a more notable one. “Nor to our knowledge are we siblings, parents, children, cousins, or any other sort of familial relation. It is, of course, theoretically possible that we share a Goodman-surnamed ancestor in some prior generation, but we have no empirical evidence that this is true,” they write.

But a satisfying ending

There is a big benefit to sharing a last name, Goodman et al argue: The accepted academic use of “et al” often grants glory to the lead author while obscuring the identities of coauthors. But ”though the many expected citations to this paper will refer to it as Goodman et al. (2015), such citations will provide equal amounts of publicity to all of us coauthors.”

Like all good academics, the authors suggest areas future researchers could explore:

Future breakthroughs on this topic should be possible. We believe much could be learned if only economists John Turner (University of Georgia), Lesley Turner (University of Maryland), Nicholas Turner (U.S. Treasury Department) and Sarah Turner (University of Virginia) would find a way to work together. Substantial progress might also come from collaboration between Janet Smith (Claremont McKenna College), Jeffrey Smith (University of Michigan), Jeremy Smith (University of Warwick), and Jonathan Smith (College Board), whose work could explore the impact of both surname-sharing and first initial-sharing. Finally, we encourage cousins Erzo F.P. Luttmer (Dartmouth College) and Erzo G.J. Luttmer (University of Minnesota) to consider collaborating for reasons too obvious to state.

The paper will be presented at 7th Annual Economics Humor Session in Honor of Caroline Postelle Clotfelter as part of the annual AEA meeting to be held on Jan. 3-5 in Boston. Past contributions to the session have included “Japan’s Phillips Curve Looks Like Japan” (Smith, G. Journal of Money, Credit and Banking 40:6, 1325-1326 [2008]), which one observer noted “consists of no other insight than the fact that a graph of the [negative] unemployment rate and the inflation rate in Japan looks strikingly similar to a map of the country of Japan.”