Welcome, Republican Congress. Your first priority doesn’t matter anymore

Update (Jan. 6): After this piece was published yesterday, the AP reported that President Obama will veto a bill from the Republican congress approves the construction of the Keystone pipeline; Democratic lawmakers say they have the votes to sustain such a veto. However, it is still possible that the executive branch, under Obama, could approve the project itself.

Update (Jan. 6): After this piece was published yesterday, the AP reported that President Obama will veto a bill from the Republican congress approves the construction of the Keystone pipeline; Democratic lawmakers say they have the votes to sustain such a veto. However, it is still possible that the executive branch, under Obama, could approve the project itself.

– – – – – – –

This week marks the inauguration of the new, Republican-controlled Congress in Washington—but events may have already rendered moot the party’s first order of business, approving construction of an oil pipeline between Canada and the US.

The Keystone Pipeline project is designed to move oil from Canada’s Alberta tar sands to US refineries, and it has been hotly contested: environmental groups and the White House fear it will generate fossil fuel emissions and contribute to climate change, whereas oil companies say it represents a huge economic opportunity.

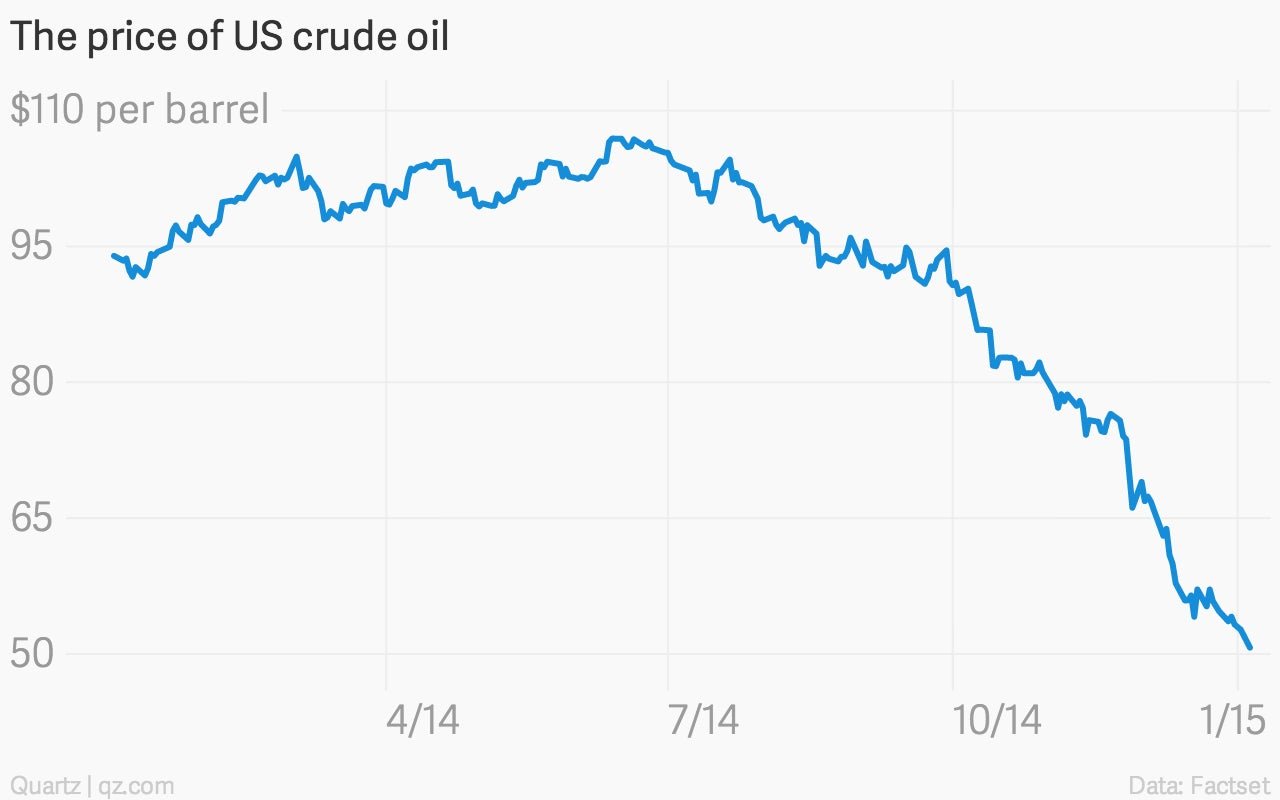

But in years of wrangling, one thing has changed: The price of oil has plunged precipitously.

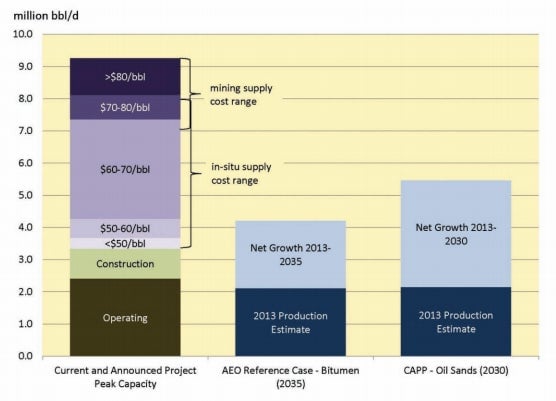

That is going to affect all kinds of geopolitical actors in 2015, but it poses particular problems for oil from the tar sands, where further investment is only really economical at prices above $65 a barrel. Already, major oil companies are pulling back. Here’s a chart from the US State Department’s environmental review (pdf) of the Keystone proposal; focus on the left column, which shows the amount of oil that can be economically accessed based on global prices.

Right now, oil prices are sitting at $51 a barrel in the US. It’s not clear whether that will last for long—analysts polled by Reuters expect the global price of oil to average $74 a barrel in 2015, but most analysts missed the recent plunge. If prices rise because of production cuts, not growing demand, that may still mean lower-than-projected production in Alberta.

Interestingly, the angle here that helps pipeline proponents is one that their opponents have used against them: cheaper oil means that transportation costs—and therefore, the pipeline—are more important to drilling the tar sands. So far, the proponents have argued that the environmental case is moot: the oil will be extracted anyhow, and the pipeline is merely a way for the US to get a share of the gains. But if building the pipeline means more pumping, that strengthens the claim that stopping it will be a win for the environment.

But the big argument from pipeline proponents—which was never really true—is that construction will mean cheap oil for the US. Now the US already has cheap oil, and that may make it easier for Obama and the remaining Democrats in Congress to sustain a veto of the project after Republicans pass it.

Obama has yet to send a clear signal over whether he will approve the pipeline, saying only that he wishes to ensure that “if, in fact, this project goes forward, that it’s not adding to the problem of climate change.” But if he does find a reason to allow the project to go ahead, it would be an important signal to the new Congress that Obama wants to work with the Republicans.