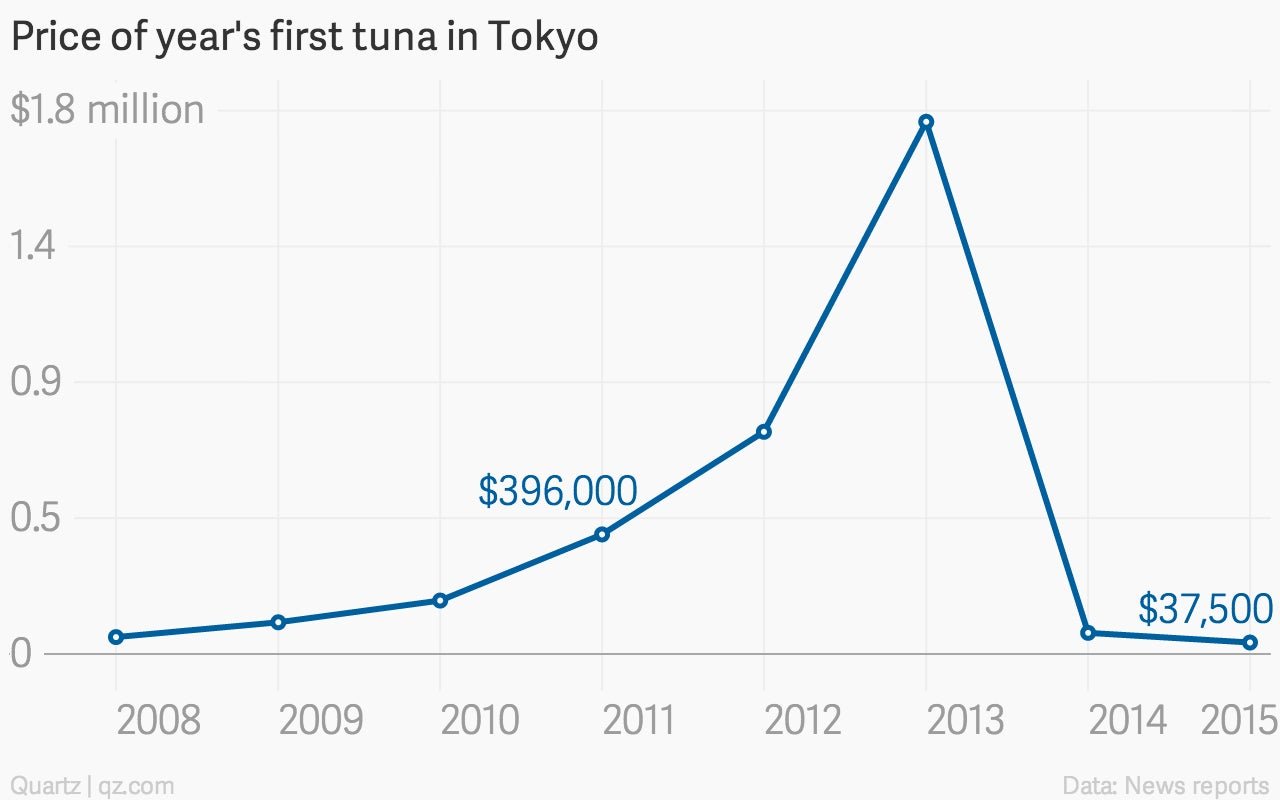

This fish sold for $37,000 at auction in Tokyo—two years ago it would have fetched $1.7 million

Japan’s first bluefin tuna auction of the year took place this weekend at the famous Tsukiji fish market, which has been in business since 1935. It’s been called “the Wall Street of Fish.” Historically, the first bluefin sold there each January has been the year’s most expensive, as a matter of ceremony. The price peaked in 2013 when a 489-lb specimen went for $1.76 million, provoking outrage among conservationists who viewed the sale as a publicity stunt symbolizing man’s ruthless plunder of the seas.

Japan’s first bluefin tuna auction of the year took place this weekend at the famous Tsukiji fish market, which has been in business since 1935. It’s been called “the Wall Street of Fish.” Historically, the first bluefin sold there each January has been the year’s most expensive, as a matter of ceremony. The price peaked in 2013 when a 489-lb specimen went for $1.76 million, provoking outrage among conservationists who viewed the sale as a publicity stunt symbolizing man’s ruthless plunder of the seas.

Global bluefin tuna populations have been dwindling for years. There are three species—the Pacific bluefin (prized by sushi eaters), the Atlantic, and the Southern—and all three are sold at the Tsukiji market. All three populations are critically low.

In 2014, perhaps as a consequence of the 2013 uproar, the same chef who had purchased the million-dollar-plus fish (and the $736,000 fish in 2012) paid only $70,000 for the ceremonial bluefin. That’s still a hefty price, all things considered, but it marked a clear departure from the showmanship of previous years.

At the first auction of 2015, the downward trend continued and the most expensive bluefin, a 400-pounder, was sold for $37,500.

For the fourth year in a row, the honor of winning the first bid went to Kiyoshi Kimura, the president of a popular sushi restaurant chain in Japan.

According to the Wall Street Journal, Kimura thinks he was able to pay so little (comparatively speaking) on account of “a successful haul of tuna near the Tsugaru strait this year.” That sounds—pardon the pun—fishy, because it’s generally accepted that the price of the first bluefin at Tsukiji is unrelated to the abundance or scarcity of available tuna. More likely, the low price this year signified a lack of rival bidders. (In 2012 and 2013, Kimura was bidding against a determined Hong Kong restaurateur to win the first fish.)

“It’s all ceremonial, it’s all about PR,” says Jamie Gibbon, who works for the Pew Charitable Trusts Global Tuna Conservation program. “The dollar amount ultimately doesn’t matter.”

Perhaps that’s the case now. But at $1.73 million, the 2013 price did matter—as a boon for global awareness of the bluefin’s plight. The auction price that year has been quoted over and over in news reports since, to show that the species is on the brink. In that regard, it’s a shame that bidding was so low on the first fish of 2015, because some might get the mistaken impression that conditions have improved for bluefin tuna. Perhaps demand is declining, or tuna stocks are recovering? Nope.

“We haven’t seen any reports of decreased demand,” says Gibbon, while the Pacific bluefin population—the tuna that swim off the coast of Japan; it’s always one of these that gets auctioned first at Tsukiji—is at 4% of its historic size. A new study by Japan’s Natural Research Institute of Far Seas Fisheries concludes that 80% fewer Pacific bluefin were born in 2014 than in 2013 (pdf, in Japanese); the population isn’t reproducing fast enough to make up for its depletion.

No wonder scientists in Tokyo and in Baltimore are trying to spawn bluefin in labs, while “tuna ranches” are popping up around the globe.