The People’s Republic of Vermont: Secession is all the rage from the deep south to Basque country

For years, secession movements have only interested staunch nationalists, reclusive cranks, and geopolitics dorks such as this author. But for a host of economic and social reasons, secession has been creeping back into the news with interesting regularity. Consider the following two events that have taken place in the last two weeks:

For years, secession movements have only interested staunch nationalists, reclusive cranks, and geopolitics dorks such as this author. But for a host of economic and social reasons, secession has been creeping back into the news with interesting regularity. Consider the following two events that have taken place in the last two weeks:

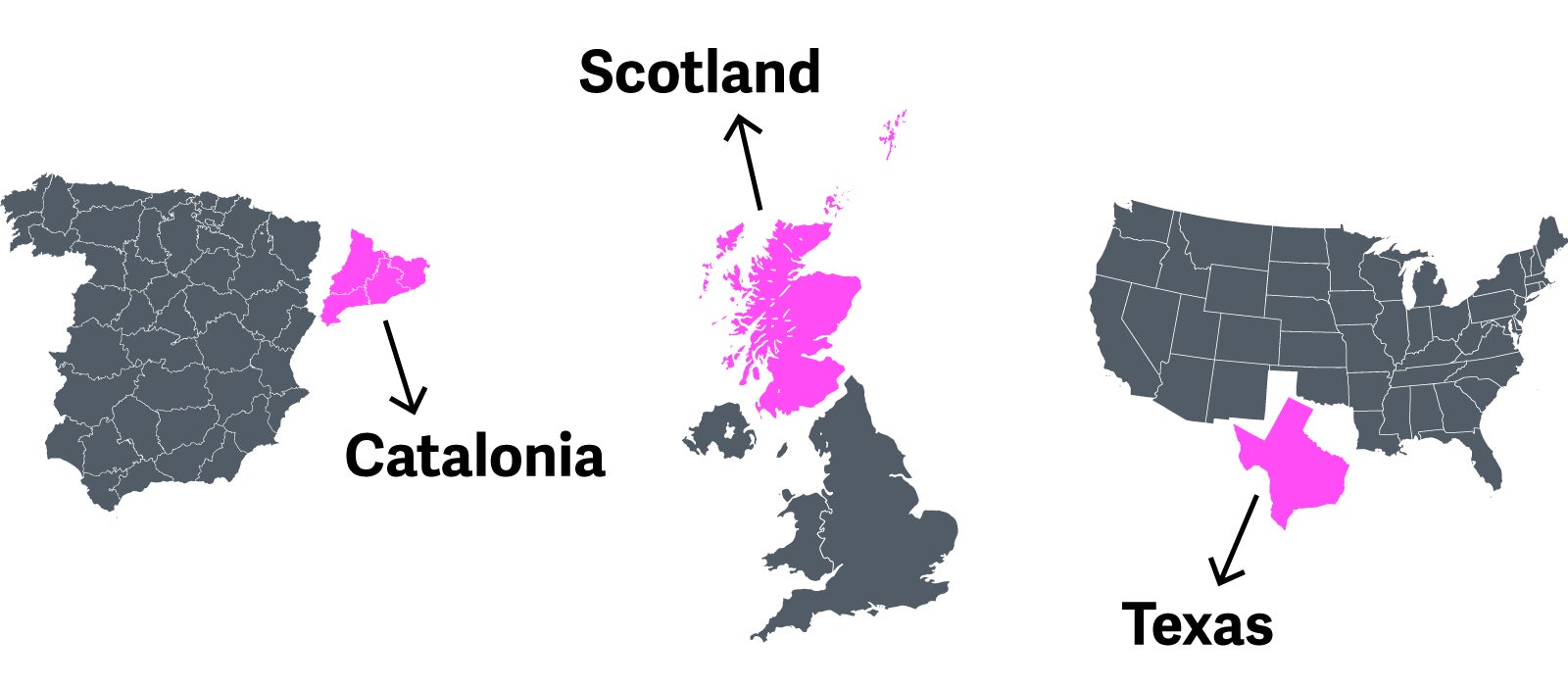

- Catalonia had a regional election that would allow Catalans the right to hold a referendum on seceding from Spain entirely, joining the European Union as a sovereign state with its own official language and national government. While Catalan separatist leader Artur Mas’ Convergenia i Unio (CiU) party actually lost seats, the separatist Catalan Republican Left (ERC) doubled its seats from 10 to 21. While it is unlikely that Mas will call for a referendum on secession immediately, the story is far from over.

- Thousands of Americans, apopleptic over the re-election of Barack Obama, have begun filling out petitions asking for the right of their state to separate from the United States of America and to form their own nation-states, including South Carolina and Texas.

There are a number of “nations” currently building a case that they require a new “state” with their own United Nations recognition. The most likely candidates are Scotland and Catalonia, but several others have been brewing separatist movements for many years, including Euskadi (the Basque country in Spain), Quebec, even the American states of Vermont, Texas and Alaska. Scotland will likely have a referendum on leaving the United Kingdom in 2014 and Catalonia is speeding toward the exit ramp , while Quebec’s last official attempt at sovereignty was back in 1995 when the 49.42% margin voting to secede scared federal Canada into giving the French considerable autonomy.

To get a clue on where the next potential nation-state might emerge, let us look at that which unites these peoples in their serious propositions to form a new nation.

Historical claim

Most states clamoring for independence did in fact have it at one point, even if it has been a while. Scotland was of course sovereign from the Middle Ages until 1707; Catalonia was its own principality until 1714; and Quebec was originally a French settlement until the Treaty of Paris in 1763 ceded it to the British Empire. The Basques have been in those hills on the Atlantic coast for millennia as world-class fishermen, navigators and ferocious soldiers. Neither Greeks, Romans, Goths, Moors nor Castilians have ever displaced or subjugated the Basques in their ancestral homeland.

Even Vermont and Texas had their own republics at one point, replete with currencies, flags, and constitutions. Vermont was the first republic on the continent between the years 1777 and 1791, joining the US only as a 200-year experiment, renewed, reluctantly for some, in 1991. Texas was a republic from 1836 until 1846, when it joined the United States, only to secede with the Confederacy in 1862. Representatives of the modern Republic of Texas movement claim that since the re-annexation of Texas in 1865 was military conquest and not legal accession, it doesn’t need to secede so much as re-recognize its inherent sovereignty.

Language

Independence movements are often galvanized by a common language not shared by the dominant state. In some cases it is very much living, as in Catalan and Basque languages which are actively spoken by the population, and in other cases the local language is moribund and needing of revitalization as in Scots Gaelic. French is far and away the official language of business, government and culture in Quebec, where it is the only province in Canada to have monolingual status; all other provinces are officially French and English for official government business. As to language in places like Vermont, Texas and South Carolina, sure they have distinct accents, but the linguistic variations would not even qualify as dialects.

Distinct culture

Many people claiming “national” status also point out notably different culture from their neighbors, from food to entertainment choices to religion. Quebec is one of the most obvious examples here, as its residents speak a completely difference language, are usually Catholic instead of Protestant, and eat different classic cuisine (poutine, tourtière, habitant pea soup). If you needed more indication of the distinct, ancient European culture of the Basques, check out their traditional sports, which include lifting anvils, chopping wood and punching holes in rocks! (“Harri zulaketa”) And the Scottish culture is distinct from their neighbors to the south—wander into a pub in Glasgow and you won’t be hard-pressed to find firsthand examples.

Economic viability

To take a secessionist movement from dream to reality, there has to be some sort of logistical viability to the group, specifically in the ability to make enough money to survive independently. In the case of Slovakia, it declared independence from “Czechoslovakia” on January 1, 1993. It was already modernizing the planned industrial economy that dated back to the Soviet communist days, and in its independence it kept developing investments in automotive manufacturing, electrical engineering, IT and finance. As a result, GDP growth has been strong ever since. Can an independent Scotland, Texas or Catalonia measure up to that kind of economic future?

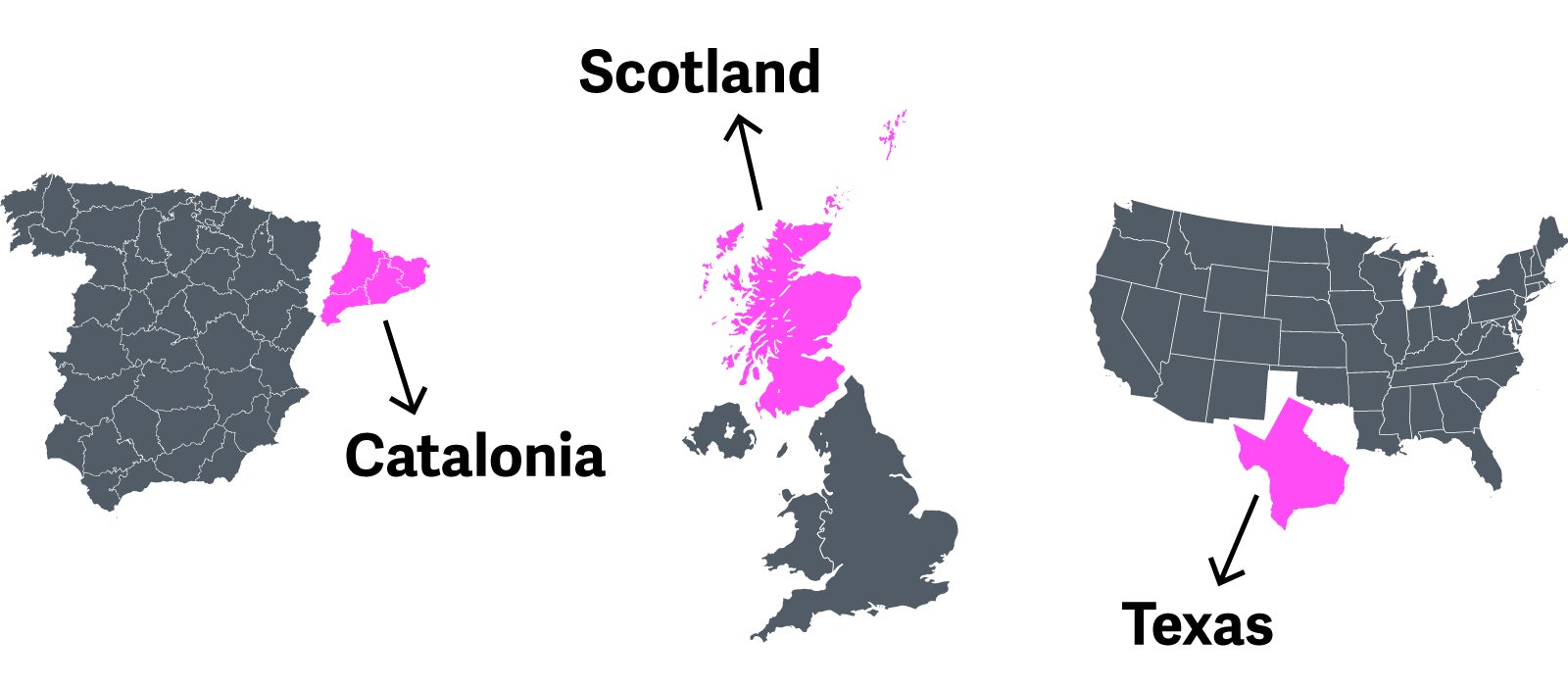

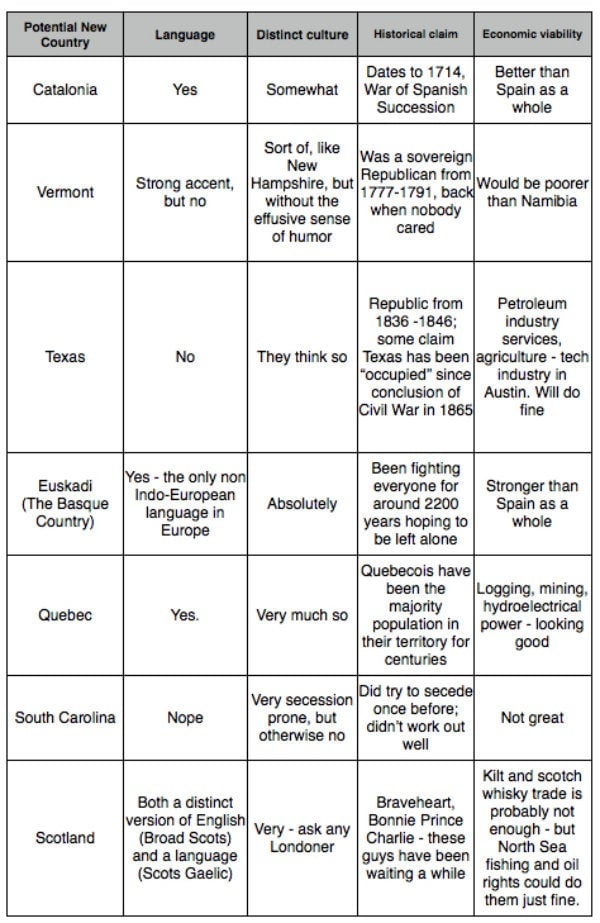

Here are the where some of the current states vying for secession fall in the above categories:

Most of the American states have weak justification for forming new nation-states as we have seen them emerge; disappointment over a political election is never enough to get a country off the ground. According to University of Vermont political science professor Frank Bryan, author of “Out! The Vermont Secession Handbook,” revulsion over the Bush Administration’s handling of the affairs of state prompted a vigorous resurgence in interest about declaring a Second Vermont Republic. But according to Bryan, the election of Barack Obama obliterated public interest in secession. It seems that people were less interested in launching a new currency, constitution and diplomatic corps, and more interested in reforming the nation-state to which they actually belonged. So we are left to wonder how serious South Carolina really is in seeking global recognition of its “national character.”

This could be enormously complicated for the rest of Europe—there are too many bonds floating around with “España” written on them that somebody needs to pay back. That heavy weight, combined with centuries of historical turbulence and distinct cultural identities, may be enough to require new seats at the UN What the bondholders might do is a much, much more complicated issue.

While the world may see some new nations on the horizon, the action will be in Europe and the Second Republic of Vermont will have to wait.