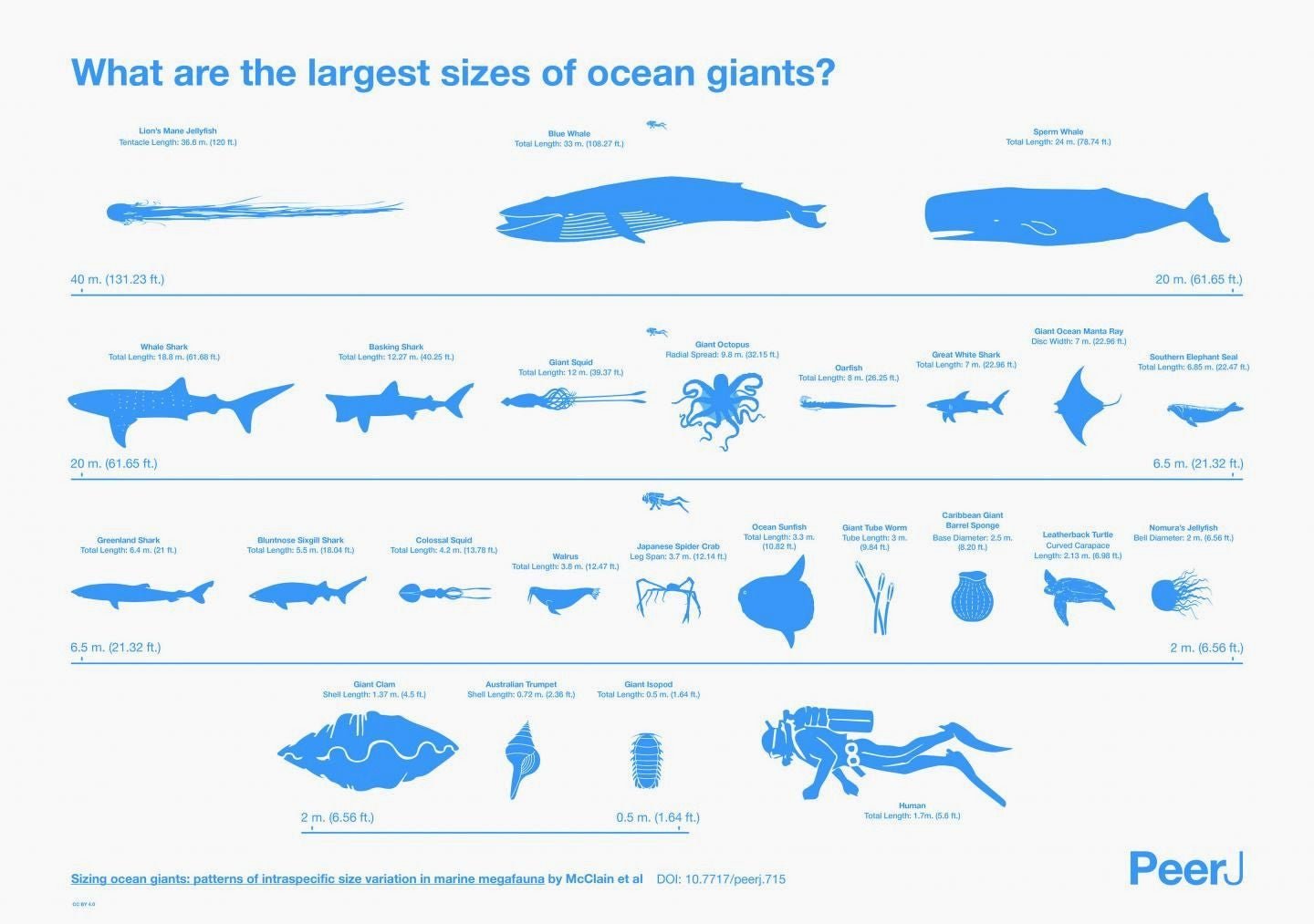

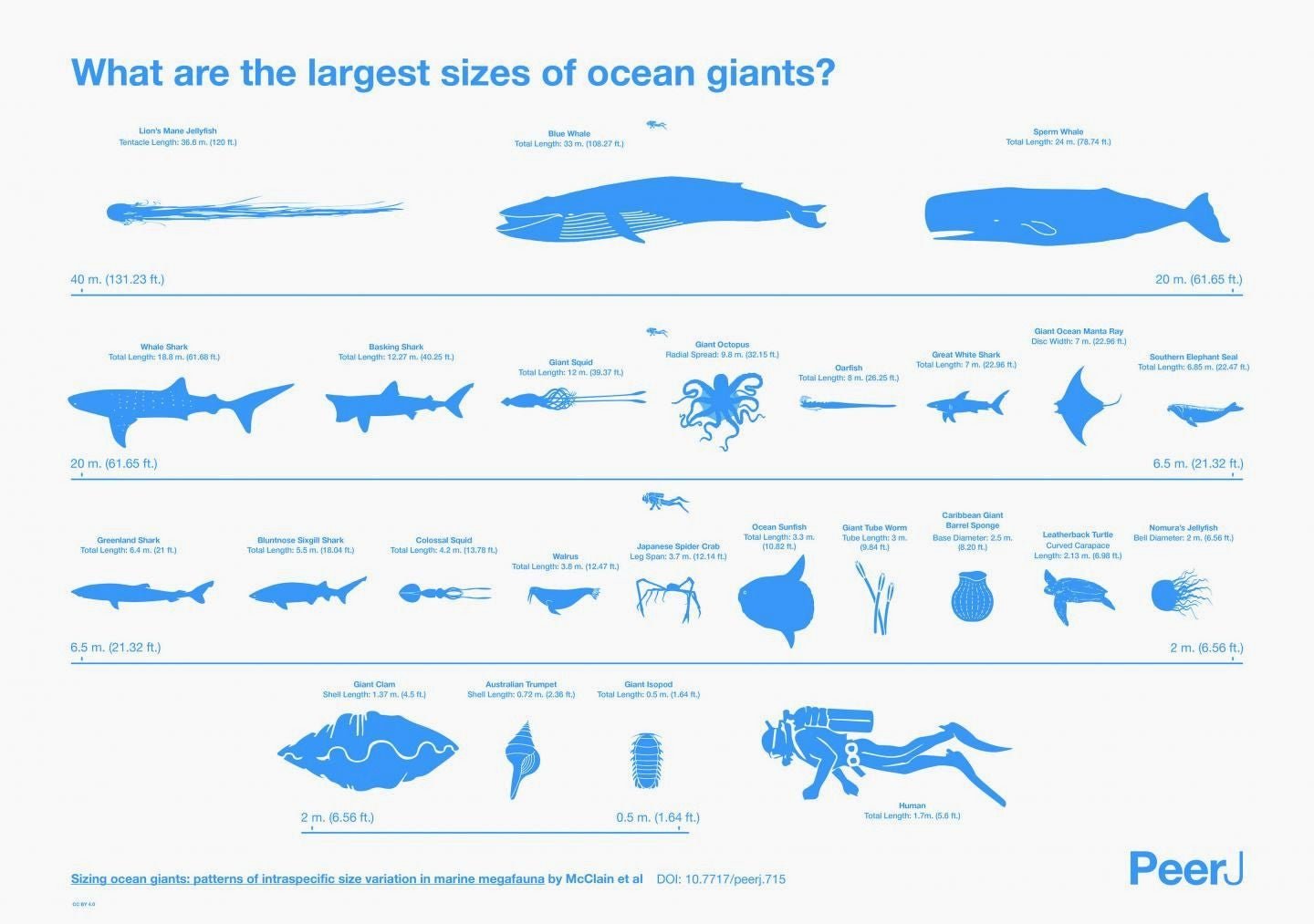

Just how huge the biggest sea creatures are—in one amazing chart

Kraken, Godzilla, Leviathan, Moby Dick—all the greatest beasties come from the depths. That’s not only true in fiction. In fact, the biggest creatures of almost every family of animal live in the sea. The chart above—from a study published today documenting the sizes of 25 marine species—shows some examples. The giant Pacific octopus that cruises the waters around Korea, Russia and Alaska, for instance, can span up to 32 feet (9.8 meters) from crown to tentacle tip. Here’s one taking down a dogfish:

Kraken, Godzilla, Leviathan, Moby Dick—all the greatest beasties come from the depths. That’s not only true in fiction. In fact, the biggest creatures of almost every family of animal live in the sea. The chart above—from a study published today documenting the sizes of 25 marine species—shows some examples. The giant Pacific octopus that cruises the waters around Korea, Russia and Alaska, for instance, can span up to 32 feet (9.8 meters) from crown to tentacle tip. Here’s one taking down a dogfish:

As for crustacean colossi, while the Japanese spider crab reaches 12 feet across, an American lobster caught in 1977 takes the prize for heaviest—it weighed just shy of 45 pounds (20.1 kg).

The sumo wrestler of the sea is perhaps the male southern elephant seal. At a whopping 22.5 feet long and weighing more than 11,000 pounds, the biggest of its species are heftier than polar bears.

What’s curious is that females of the species are about half the size of males. Scientists think this has something to do with the need to defend their harems. When their harems are reproducing, males must fast to protect them—which is probably why successful dads are those that have put on the most blubber. Plus they also have to be able to clobber any male competitors.

And who can think of sea monster without imagining Jaws? Despite the great white shark’s high profile, the actual size of the biggest every recorded is still controversial. A great white caught off Mallorca in 1969 supposedly measured 26.2 feet, while two others caught in 1987 were around 23 feet. Scientists estimate the range is somewhere between 15 and 26.9 feet.

When the dazzle of these marine behemoths wears off, other mysteries remain. For instance, why do some animals grow so large—and what’s keeping the rest of their species from doing so?

For animals like the southern elephant seal, size probably helps discourage would-be predators. But size isn’t always an advantage. Take jellyfish, for example. The rarely sighted lion’s mane jellyfish that haunts chilly northern waters can extend 120 feet, according to one account. But its tentacles are so long they’re cumbersome, making them more vulnerable prey. Meanwhile, the heaviest jellyfish—the Nomura’s jellyfish—can weigh more than 440 lbs. At some points in its lifecycle it can eat so much that it grows 10% a day—like sprouting an extra thigh every morning. But because they can’t propel themselves, once the bigger of the species have gobbled up all the surrounding nutrients, meal-time is over, curbing further growth.

As real as these big sea-beasts are, they may increasingly become a thing of myth, thanks largely to how humans are warping the ocean. For instance, overfishing and habitat destruction mean that giant mantas are no longer reaching their maximum sizes in many places. As for sperm whales, a century of hunting, which targeted the biggest of the species, pushed their sizes down over time; most populations never recovered. And so polluted are the waters where the giant Pacific octopi thrive that scientists think heavy metals and toxic chemicals are impairing their growth.