Nigerians have a lot of issues—but they’re all about one right now

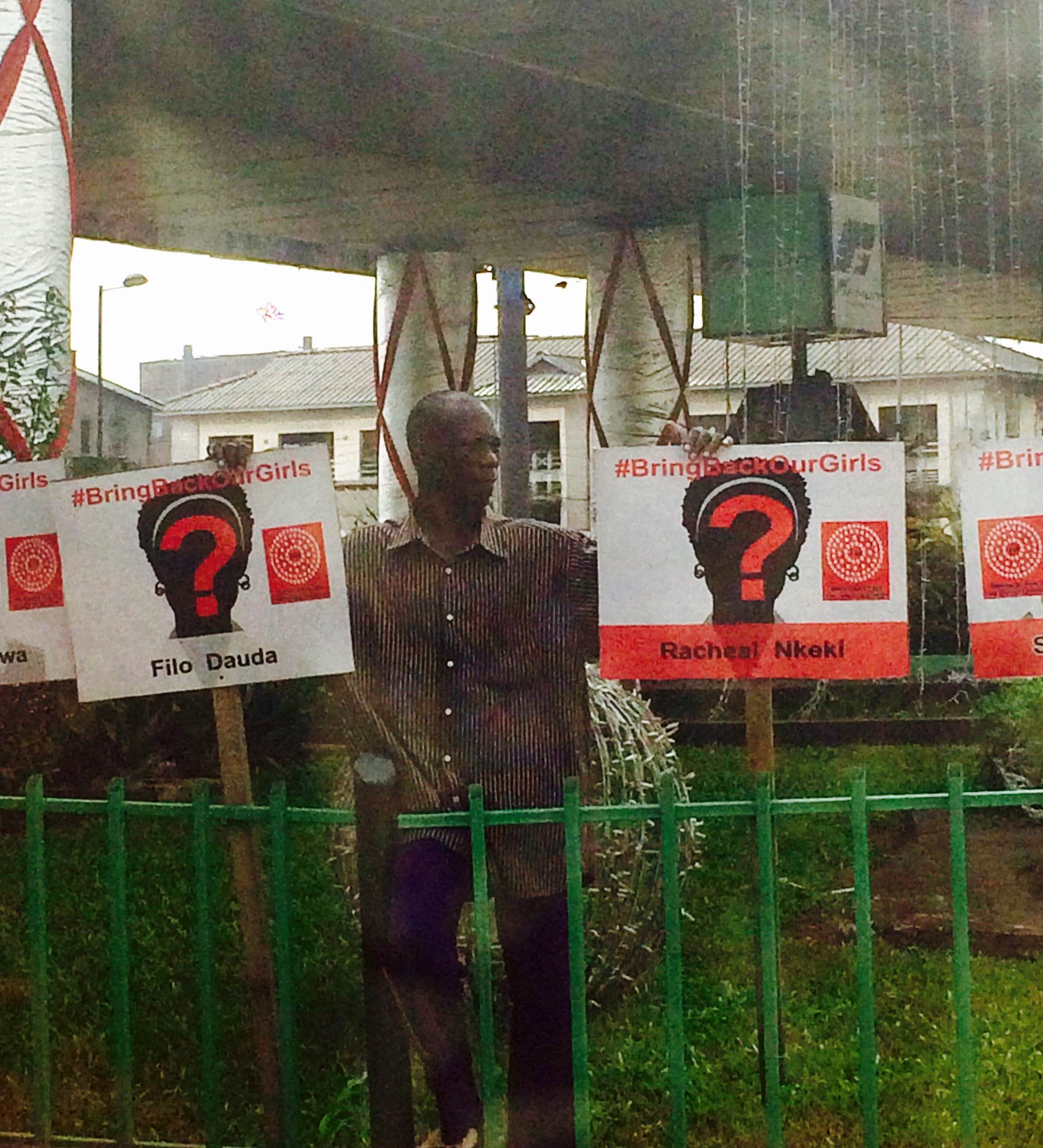

LAGOS, Nigeria—For most of 2014, a traffic roundabout in central Lagos was adorned in cardboard cutouts of the names of 200 Nigerian schoolgirls kidnapped by the terror group Boko Haram in April.

LAGOS, Nigeria—For most of 2014, a traffic roundabout in central Lagos was adorned in cardboard cutouts of the names of 200 Nigerian schoolgirls kidnapped by the terror group Boko Haram in April.

By now, the makeshift memorials have toppled and faded—reflecting the flagging crusade to bring the girls back, the failing crusade to stop the violence.

I arrived in Nigeria a month ago to the news that Boko Haram had just kidnapped another 185 people and killed 32 more. January has brought the same trickle of horrifying news from Borno State in the northeast: as many as 2,000 people were gunned down in the village of Baga, and a 10-year-old girl had been used as a suicide bomber in Maiduguri.

The most worrisome part of the affair is not that the murders are accelerating in volume and boldness—but that there is a federal election to be held in less than a month. The Nigerian election authorities recently confirmed that the vote scheduled for Feb. 14 would go on in Borno, Yobe, and Adamawa states, the three mostly Muslim polities in which a state of emergency has been declared since 2013.

This election is about just one thing: Security. It is the decisive issue in the campaign between president Goodluck Jonathan and his main opponent, General Muhammadu Buhari. Given Nigeria’s plummeting oil revenues, the recent devaluation of the naira, corruption scandals, continuing energy shortages and unemployment woes, that’s saying something. But the terror threat has given Buhari an advantage in a system that has always favored incumbents.

Akin Oyebode, a finance analyst who served as a soldier in Maiduguri 10 years ago, spoke of his 19 month old son. “I do not want him to grow up in a country where brothers are killing themselves… where people cannot afford to travel to parts of their country out of fear,” he said.

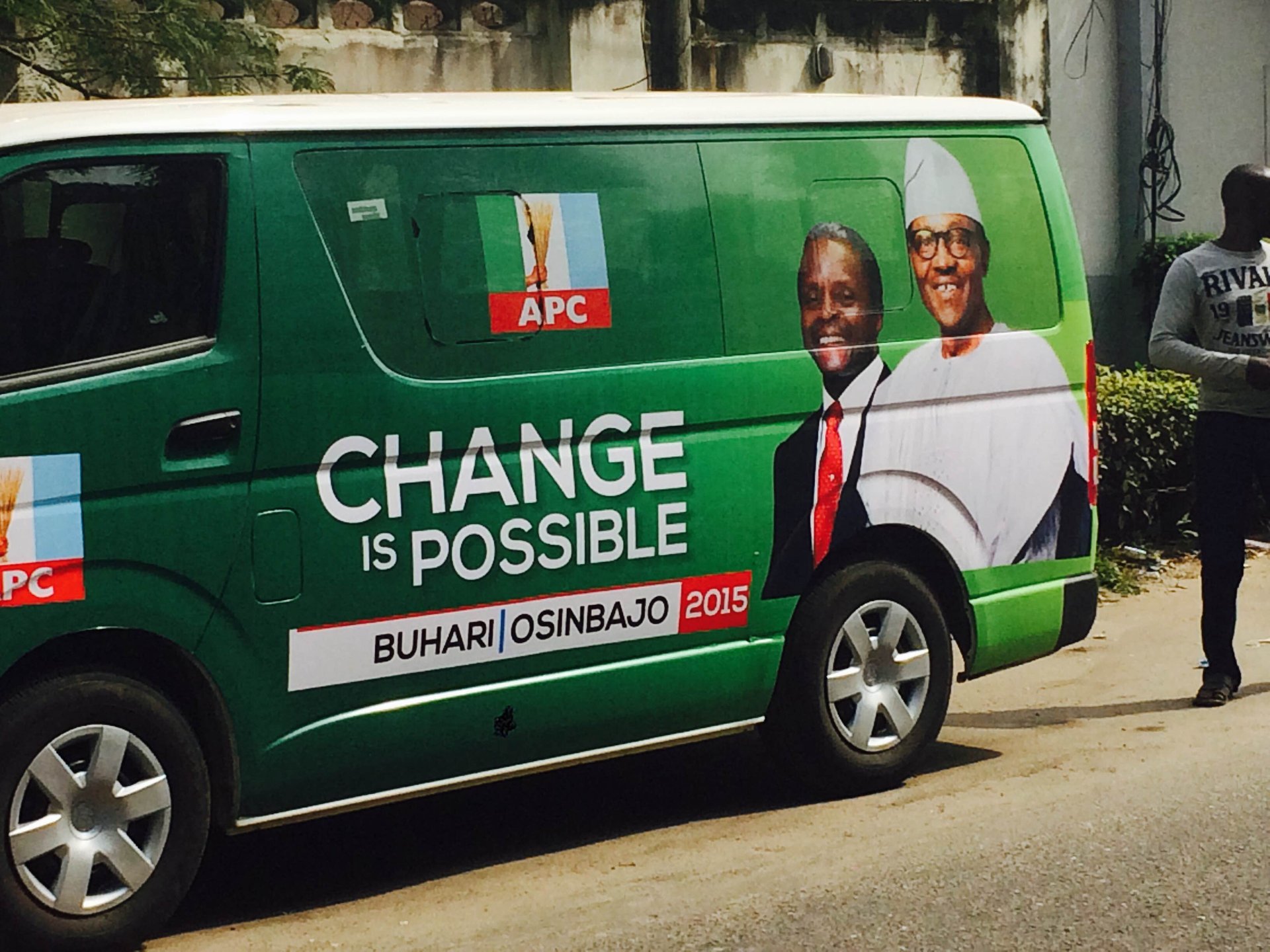

It’s no surprise that Lagos (a stronghold of Buhari’s party, the All Progressives Congress) is blanketed in advertisements for he and his running mate, former attorney general Femi Osinibajo. But in Enugu, a city in the southeast expected to back Jonathan, several thousand supporters flocked to a Buhari rally carrying traditional brooms and thistles—mirroring the APC’s populist logo. In Jos, capital of Plateau State, one of three crucial middle belt states that will likely determine the election’s winner, a group of youth set Jonathan’s campaign buses alight. And for better or worse, Mend, the terror group from Jonathan’s backyard in the Niger Delta, recently threw its endorsement to Buhari.

Jonathan has his record to blame. Boko Haram has launched more than 80 discrete attacks during his presidency. While Nigerian troops have intermittently engaged the terror group, most recently repelling insurgents in the northern town of Damaturu, his government has been unsuccessful in curbing the violence. Despite offers of partnership from the US military, the most effective action against Boko Haram in the last month came via neighboring Cameroon, whose cross-border airstrikes in late December and early January have killed a total of 184 insurgents. According to some estimates, Boko Haram still controls 70% of Borno State.

Security concerns will affect the vote no matter what: Hundreds of polling stations in the northeast will test Boko Haram’s appetite for spectacular violence. And more than 1 million internally displaced people from the areas wracked by insurgency may not be able to vote at all.

Kicking off his campaign last week, as the horror in Baga was coming to light, Jonathan did not mention Boko Haram by name. He blamed military blunders on equipment that his predecessors had failed to procure. He later condemned the Jan. 7 attacks in Paris, but said not a word about Baga.

The president may have underestimated popular indignation at the crisis in the rural northeast. The Nigerian public has long had low expectations of its democratic institutions. Many grudgingly provide for themselves what the state does not—schooling, electricity, and health care. Though terrorism only affects a small proportion of the population, it’s come to stand in for state failure across the board.

This helps explain the warmth of welcome for Buhari, a candidate who turned 72 years old in December, and who counts this as his fourth bid for the presidency. The general trained at the US Army War College and served as head of state for 18 months in 1984. For older generations, he was the opening act for a military dictatorship that presided over the country’s so-called lost decade. Others are attracted to Buhari’s reputation as a crusader against corruption. His “war against indiscipline” jailed thousands in the 1980s.

But really, it’s the threat of Boko Haram that gives Buhari the possibility of an Act 2.

Buhari served briefly as governor of what was then known as Northeast State, a territory comprising Borno, Yobe, Adamawa, and a handful of other states bordering Niger, Chad, and Cameroon. When, at a recent campaign event, he told a story of shuttling between Jos and Maiduguri to negotiate engagement with Chad’s army after that country’s military coup, the crowd of mostly young men clapped and whistled.

Martins Arogie, a senior manager at KPMG in Nigeria, said, “We are faced with two options: A man whose record we can see, and whose record does not represent the change we know we want. And a man who was there for a fleeting moment in the past, and what he did then seemed to us like what we need now.”

Babatunde Fashola, the Lagos state governor, put it tactfully at the Buhari event: “In my study of history, there is never a leader for all times. There are leaders for the moment,” he said.