Why most CEOs will never be Steve Jobs

CEOs are chosen to have good general management and leadership skills but many don’t have the specialist skills needed to lead innovation. In 2006, Nokia, then the world leader in mobile phones, appointed Olli-Pekka Kallasvuo as CEO. He had been with the company since 1980. So he had many years of industry experience. But he had studied law at University of Helsinki, worked at Nokia first in the legal department, and then in finance. His educational and career background didn’t qualify him to direct new product development although the future of Nokia was, at the time, critically dependent on successful new product launches. In 2006, Apple had Steve Jobs as CEO. Apple and Jobs had never produced a phone. But Jobs had a long history of personally leading the successful development of new, hi-tech products and phones were becoming smarter and more like computers. You would have been right to back Apple and Jobs over Nokia and Kallasvuo to come up with an innovative new mobile phone.

CEOs are chosen to have good general management and leadership skills but many don’t have the specialist skills needed to lead innovation. In 2006, Nokia, then the world leader in mobile phones, appointed Olli-Pekka Kallasvuo as CEO. He had been with the company since 1980. So he had many years of industry experience. But he had studied law at University of Helsinki, worked at Nokia first in the legal department, and then in finance. His educational and career background didn’t qualify him to direct new product development although the future of Nokia was, at the time, critically dependent on successful new product launches. In 2006, Apple had Steve Jobs as CEO. Apple and Jobs had never produced a phone. But Jobs had a long history of personally leading the successful development of new, hi-tech products and phones were becoming smarter and more like computers. You would have been right to back Apple and Jobs over Nokia and Kallasvuo to come up with an innovative new mobile phone.

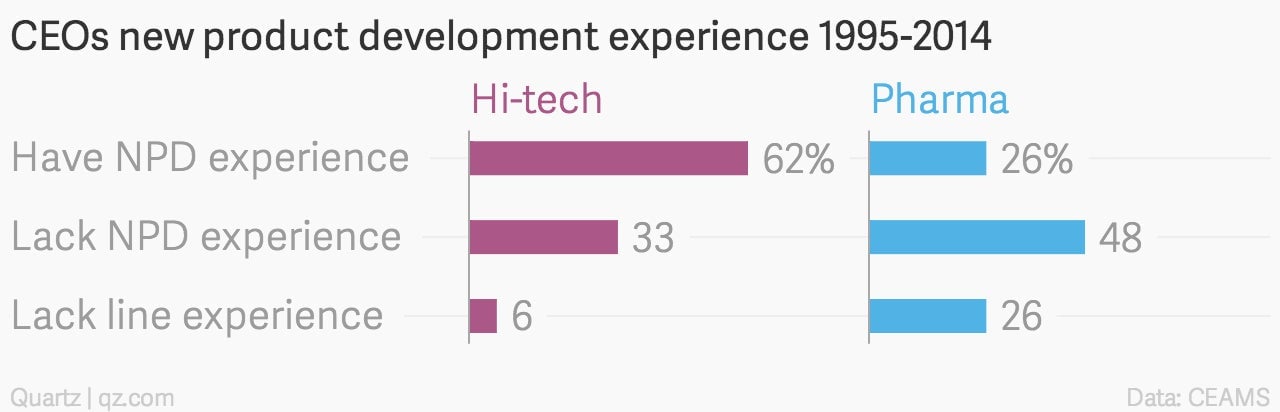

Kallasvuo is not an isolated exception. Dr Julia Bistrova and her research team at CEAMS, a Swiss asset management business focused on investments in quality companies, have systematically examined the educational and career background of CEOs of major North American and European stock-market listed firms. Over the past 20 years, the overwhelming majority of CEOs have had at least several (typically many) years of line management experience—working in a general management position or in a core business process such as sales—in their industry before becoming CEO. But only about half have had the combination of relevant formal education—if you want to lead new product development in a hi-tech company, it is better to have a degree in computer science than American history—and line management experience in new product development that would qualify them to personally lead innovation.

The picture is more dramatic in the pharmaceutical and bio-tech industry. There, only 26% of CEOs over the past 20 years have had a scientific or medical education and direct work experience in pharmaceutical research and development. And a full 26% have had little or no line management experience of any kind in the industry before becoming CEO. Among current CEOs, Kenneth Frazier at Merck has a background, for example, as a corporate counsel. Severin Schwan at Roche worked his way up through finance. Joe Jimenez was hired by Novartis after working for Heinz in consumer brands marketing. And Robert Bradway at Amgen spent much of his career in investment banking.

In hi-tech, more CEOs, 62%, have had the education and career background required to personally lead innovation. For example, Satya Nadella at Microsoft, Steve Mollenkopf at Qualcomm, Lisa Su at Advanced Micro Devices (AMD) or Jen-Hsun Huang at Nvidia, all have both multiple engineering degrees and substantial experience in developing new hi-tech products.

In recent decades, the hi-tech industry has a strong track record of innovation, the pharmaceutical industry less so. There has been a pick-up in new drug approvals in the past three years but, but in the first decade of the new millennium, pharma companies were spending much more on research and development to develop significantly fewer new drugs than they did in the 1990s. The cost to develop a successful new drug increased sharply—on some estimates by a factor of six. So the need to increase research and development productivity has been a top issue in pharma. Yet commentators on big pharma companies’ research and development difficulties seldom mention CEO qualifications as a problem. That is odd since some of the best performances in introducing new drugs have come from companies headed by CEOs who have a strong research and development background such as Jean Paul Clozel at Actelion, Arthur Levinson at Genentech, or John Martin at Gilead.

Granted, companies whose CEOs lack strong qualifications to lead new product development can set things up to work around the problem. For example, GlaxoSmithKline (GSK) research and development performance has recently been strong. Sir Andrew Witty, the CEO since 2008, has a sales and marketing, not an research and development background. But GSK has carefully organized research and development to be successful in innovation with much less direction and control from the top. Much of GSK’s research and development is carried out in strategic partnerships with smaller firms. GSK’s own internal research and development is organized into many autonomous units that are dependent for renewed project funding on investment boards, which include both GSK employees and external members. Or, at Novartis, where Joe Jimenez lacks the career background to set the strategy for research and development, there is an independent Chairman of the Board, Joerg Reinhardt, who has a PhD in pharmaceutical sciences and a career background in pharmaceutical development.

Certainly, innovation isn’t the only way to create shareholder value. Thinking short term, a successful acquisition and post-merger integration program or aggressive cost reduction may add more value than innovation. But in the long term, innovation is critical to company value creation and, if the CEO doesn’t have the personal background to lead innovation, shareholders should be asking tough questions about how the company is set up to innovate in spite of that. It is not just shareholders of pharmaceutical companies that should be asking those tough questions. Hi-tech CEOs appointed over the past decade are less likely to have the background to lead new product development than their predecessors. Tim Cook, Job’s successor as CEO at Apple, has a production management background. Mark Hurd and Safra Catz have recently been named co-CEOs at Oracle. Katz has a finance background and Hurd, (like Bill McDermott who is now CEO at Oracle competitor SAP) a background in sales and marketing. Without a personal pedigree in new product development, these CEOs must organize smarter and get more support to make sure their companies can successfully innovate.