Why bright, low-income US students don’t apply to better colleges

When asked in a research survey why they didn’t apply to a selective US college, one high-achieving, low-income student showed his misunderstanding of the commonly used term “liberal arts” (which refers to a college offering a broad range of arts and sciences):

When asked in a research survey why they didn’t apply to a selective US college, one high-achieving, low-income student showed his misunderstanding of the commonly used term “liberal arts” (which refers to a college offering a broad range of arts and sciences):

“I am not liberal,” he wrote.

Many bright, economically disadvantaged US students end up at colleges with poor track records, even if they would pay less at better institutions after receiving financial aid, according to research from Caroline Hoxby of Stanford, and Christopher Avery of Harvard. Many don’t even apply to any selective schools, despite those schools seeking diversity in their student bodies. It’s a waste of academic talent, a contributor to inequality, and a drag on economic mobility.

Bad information is the cause, according to a new NBER working paper (paywall) from Hoxby and Turner—and that’s a problem that’s eminently fixable. Students are misinformed about cost: They experience sticker shock at schools that cost $50,000 a year and up, and they don’t realize that the net price they would actually pay with financial aid is much lower, often below $10,000.

The study focuses on 12,000 students who scored in the top 10% on the standardized tests known as SAT and ACT, came from a family in the bottom third of the country’s income distribution, and didn’t attend a school that tends to feed into highly selective institutions.

Many of these students are also badly informed about how they match up with schools. They think “college is college,” or assume they wouldn’t fit in at a particular school, without knowing much about the different resources available, or their comparative career and income outcomes.

A list of responses from the survey shows that many students lack basic information about private liberal arts colleges:

“What is a private liberal arts college?”

“I don’t know what this is”

“I don’t like learning useless things”

Some showed misperceptions about the offerings available:

“I don’t like art/art related subjects.”

“I’m a math/science guy. I’m not very good at liberal arts.”

“Liberal arts is for people who aren’t good at math.”

“Liberal arts colleges typically do not have mathematics majors.”

Or bad information on outcomes:

“I plan on attending medical school.”

“I plan on grad school later.”

“Liberal arts degrees are worthless”

“Limited future career options”

Many liberal arts schools have strong engineering, hard science, and math programs, good career outcomes, and high graduate school placement rates. The school with the single highest return on investment of any American institution is an engineering-focused liberal arts school.

But the researchers found that students make dramatically different (and better) decisions when simply given more information. They designed a program for this type of student: ECO-C, short for “Expanding College Opportunities. It had an extraordinary effect on applications, admissions, and decisions.

The program offered personalized information on the real cost students could expect to pay, the variation in what schools spend on instruction and academics, and graduation rates, and offered a no-paperwork fee waiver for about two hundred selective schools. It gave no school recommendations, just better tools and information.

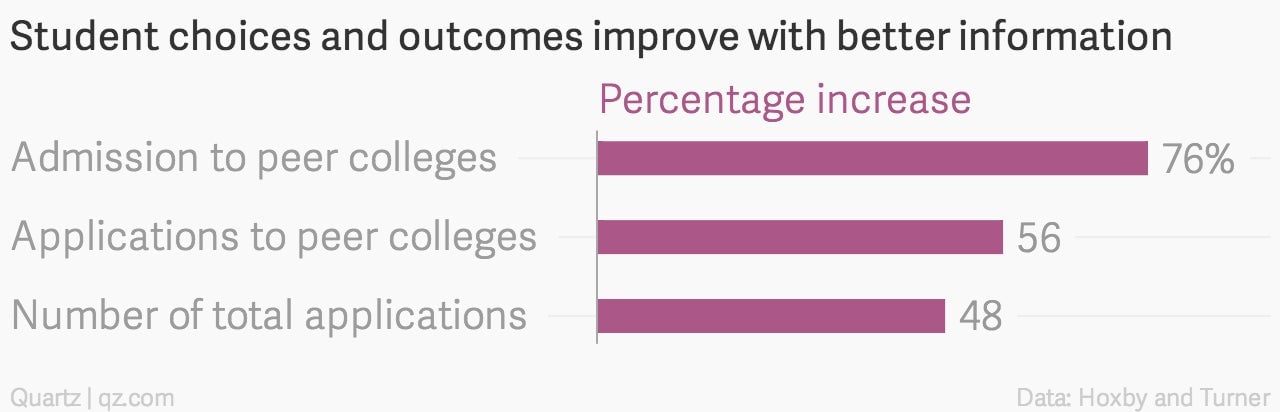

Here’s the effect on application decisions (where a “peer” institution is one that fits the student’s level of academic achievement and preparation). Students applied to and were admitted by more selective schools with higher graduation rates and higher spending per student, compared with those in a control group who didn’t get extra information:

These students were 46% more likely to enroll in a peer college. They were accepted to 41% more schools overall, and ended up at schools with 15% higher graduation rates, and 21.5% more instructional spending.

This was just a small, pilot program. But it shows just how much giving people extra facts helps. And it’s a low-cost way (around just $8 per student) to produce far better outcomes for low-income students.