2014 was a real rhino-slaughtering bonanza

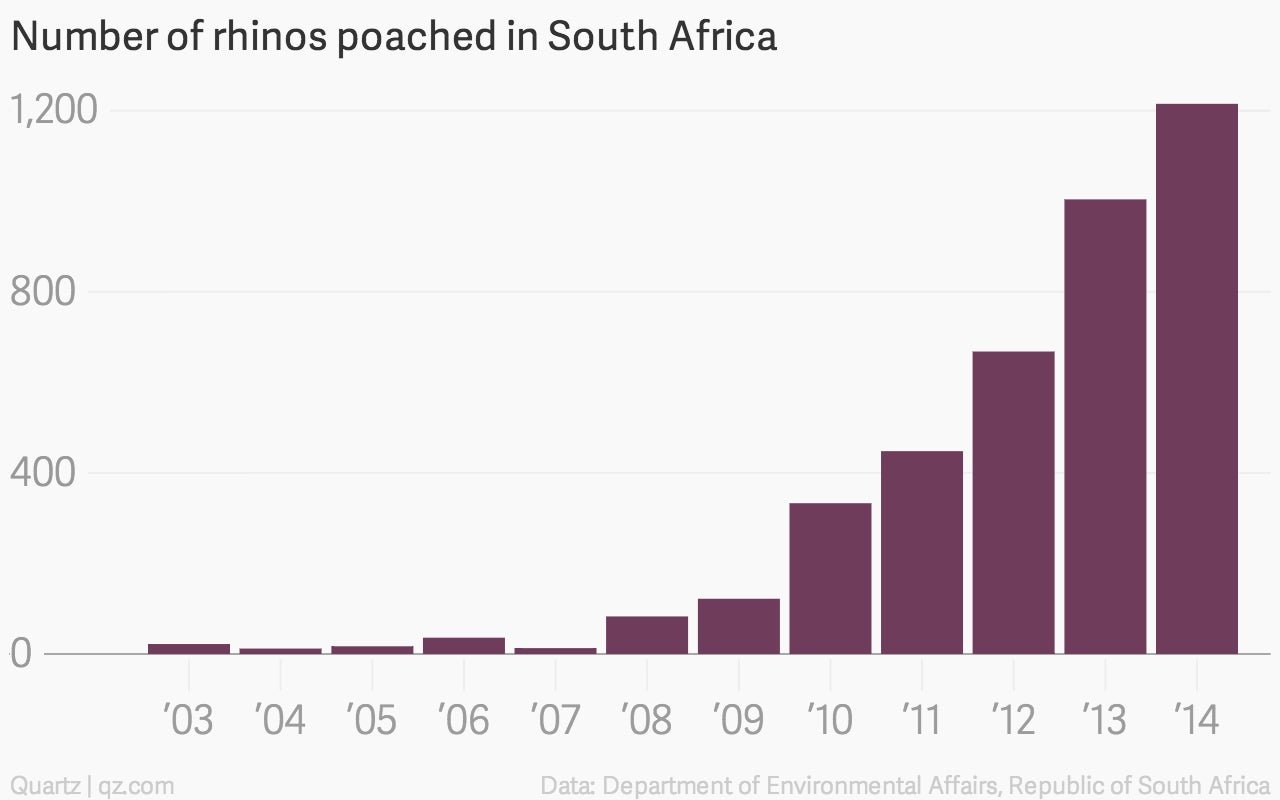

Poachers in South Africa killed 1,215 rhinos last year—an increase of more than 20% from 2013. What’s driving the country’s poaching crisis is the value of its horn, which is prized in Asia—particularly in Vietnam and China—for its supposed medicinal and narcotic purposes. Rhino horns can sell for more than $66,000 a kilogram (about $30,000 per pound) on the Chinese black market, according to Chatham House, a think tank.

Poachers in South Africa killed 1,215 rhinos last year—an increase of more than 20% from 2013. What’s driving the country’s poaching crisis is the value of its horn, which is prized in Asia—particularly in Vietnam and China—for its supposed medicinal and narcotic purposes. Rhino horns can sell for more than $66,000 a kilogram (about $30,000 per pound) on the Chinese black market, according to Chatham House, a think tank.

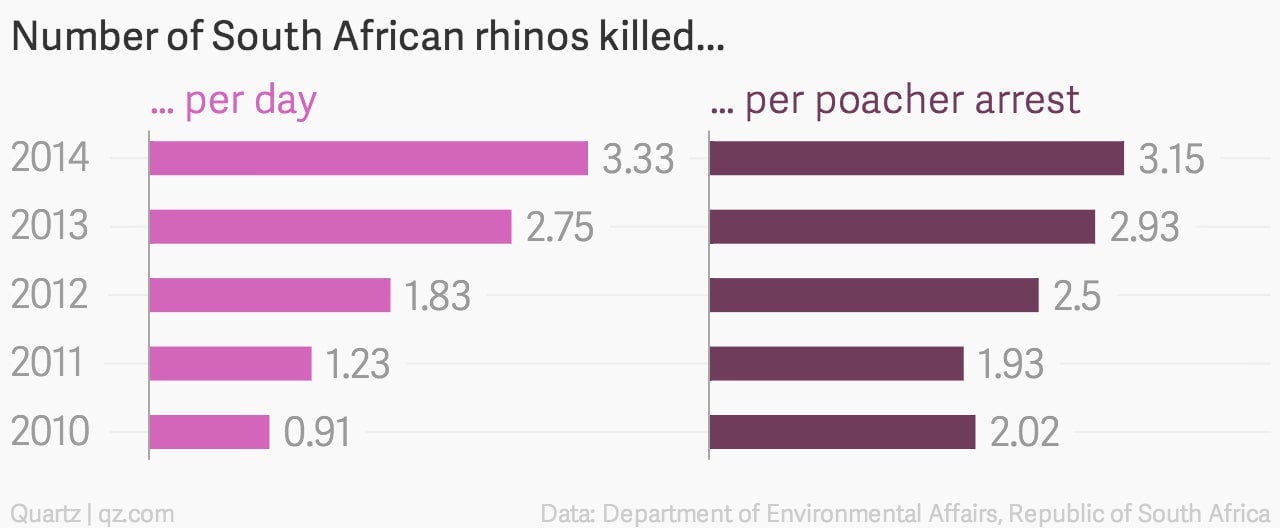

Last year’s slaughter may have already pushed South Africa’s population into decline, says Traffic, a non-governmental wildlife crime monitoring group. On average, poachers killed more than three rhinos each day of 2014.

That’s a staggering rate considering only 18,000 South African white rhinos remain in the wild, according to a 2013 study (paywall)—so few that if poaching continues at current rates, Africa’s rhinos may be extinct in the wild within 20 years.

Due to threat of rhino extinction, international trade of their parts has been illegal since 1977—artificially restricting supply, argue some, and thereby inflating prices so much that an intricate global organized crime syndicate now runs the trade.

But the booming black-market trade is less than a decade old; a single horn fetched only $760 in 2006, versus $57,000 last year. Though Chinese traditional medicine has long cited rhino horn’s medicinal properties, the recent surge in prices—and, therefore, in rhino killings—began in 2007, when rhino horn gained a reputation in Vietnam as a cancer cure-all and designer club drug.

Despite 2014’s record-breaking death toll, the Vietnamese government says its three-year campaign debunking the myth of rhino horn medicinal benefits appears to have had some success.

However, problems on the supply side remain, says Traffic. Delays of key prosecutions, corruption and mismanagement of its anti-poaching police force have weakened South Africa’s protection efforts, says the group.

In a statement today, South Africa’s environment minister, Edna Molewa, praised South Africa’s anti-poaching efforts, while conceding that the number killed “remains worryingly high.”

She also noted that the government is still researching the case for legalizing the rhino horn trade, which it plans to propose to the international regulator in 2016.

The idea wouldn’t be as cruel and unwieldy as it sounds. Made of keratin, the horn can be shaved off without hurting the animal—and, as with fingernails, another will eventually regrow in its place. This would deflate prices—and by leaving rhinos hornless, literally cut off illegal supply—driving crime syndicates out of the poaching business. Profits could fund South Africa’s conservation efforts, which become more expensive as militarized poacher gangs grow. Peru pulled off a similar feat in the 1990s to save the vicuña, a soft-wooled llama-like creature.

There are some catches, though. Humane dehorning is expensive, and as Zimbabwe’s experience indicates (pdf), can leave enough stump to attract poachers. Since nub-nosed rhinos lack the photographic appeal of those with horns, dehorning might diminish the rhinos’ tourism value.

Peru’s experience with the vicuña wasn’t seamless, either. Cristian Bonacic, an architect of Peru’s plan, tells National Geographic that the legal wool industry stimulated even more demand, spurring even more poaching, something he fears global trade networks will exacerbate. The rhino population is also more fragile. When the legal wool trade began, there were a lot more wild vicuñas than there are rhinos, says Bonacic.