What you need to know about the election in Greece

“In Greece, democracy will return,” Alexis Tsipras said as he voted on Sunday in his nation’s general election. The 40-year-old leader of the radical left Syriza party is likely to be the next prime minister of what is after all the birthplace of democracy.

“In Greece, democracy will return,” Alexis Tsipras said as he voted on Sunday in his nation’s general election. The 40-year-old leader of the radical left Syriza party is likely to be the next prime minister of what is after all the birthplace of democracy.

Tsipras’s imminent ascendancy to the top of Greek politics holds consequences, not only for his country but for all the 19 members of the euro zone.

Why are voters turning to Syriza?

Because Greece has been a depressing place to live in the last five years.

In late 2009, Greece—after much umming and ahhing—re-stated its accounts and said its debts were the highest in the country’s modern history. In 2010, it received a 110-billion-euro bailout from the euro zone. That wasn’t enough, and in 2012, another 130-billion-euro bailout was agreed upon by international lenders in return for a series of major spending cuts.

Syriza—then a coalition of leftist parties rather than a single entity—almost derailed the second bailout by winning the most votes in a general election in May 2012 on an anti-austerity platform that called for leaving the euro and returning to the drachma. But a second election was held six weeks later, won by a traditional party that backed the bailout, and Greeks have had it even tougher since then.

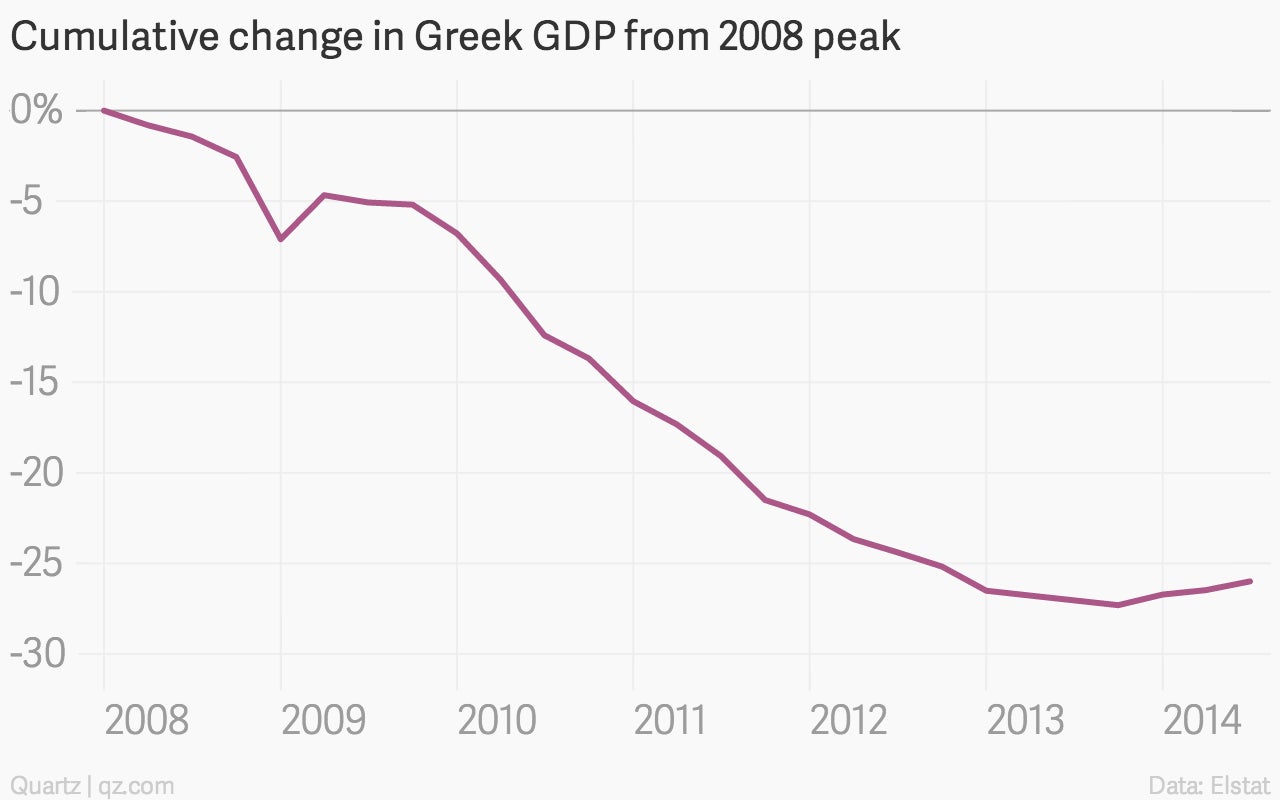

Roughly 25% of the Greek economy has been destroyed since the peak in late 2007, putting its tumble

:

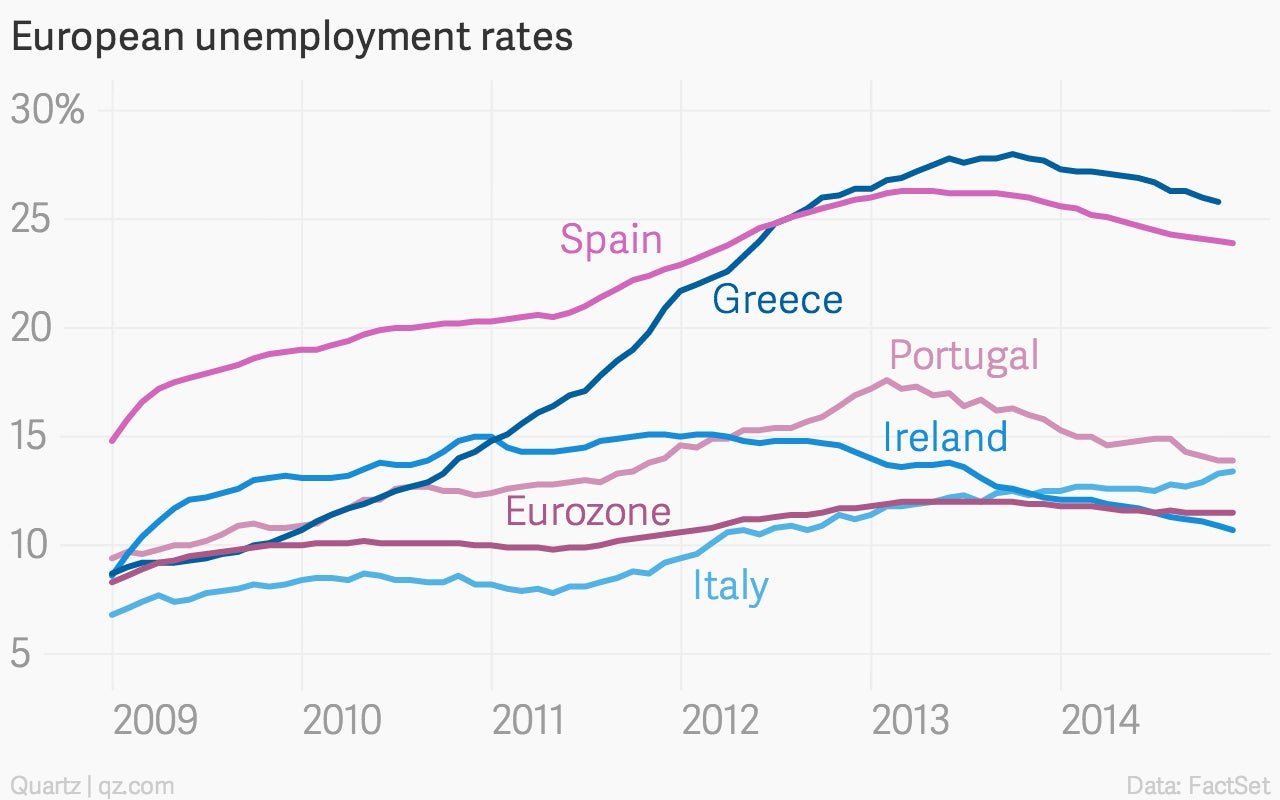

Unemployment shot through the roof. Currently, about 26% of people in

(pdf), the highest in the European Union:

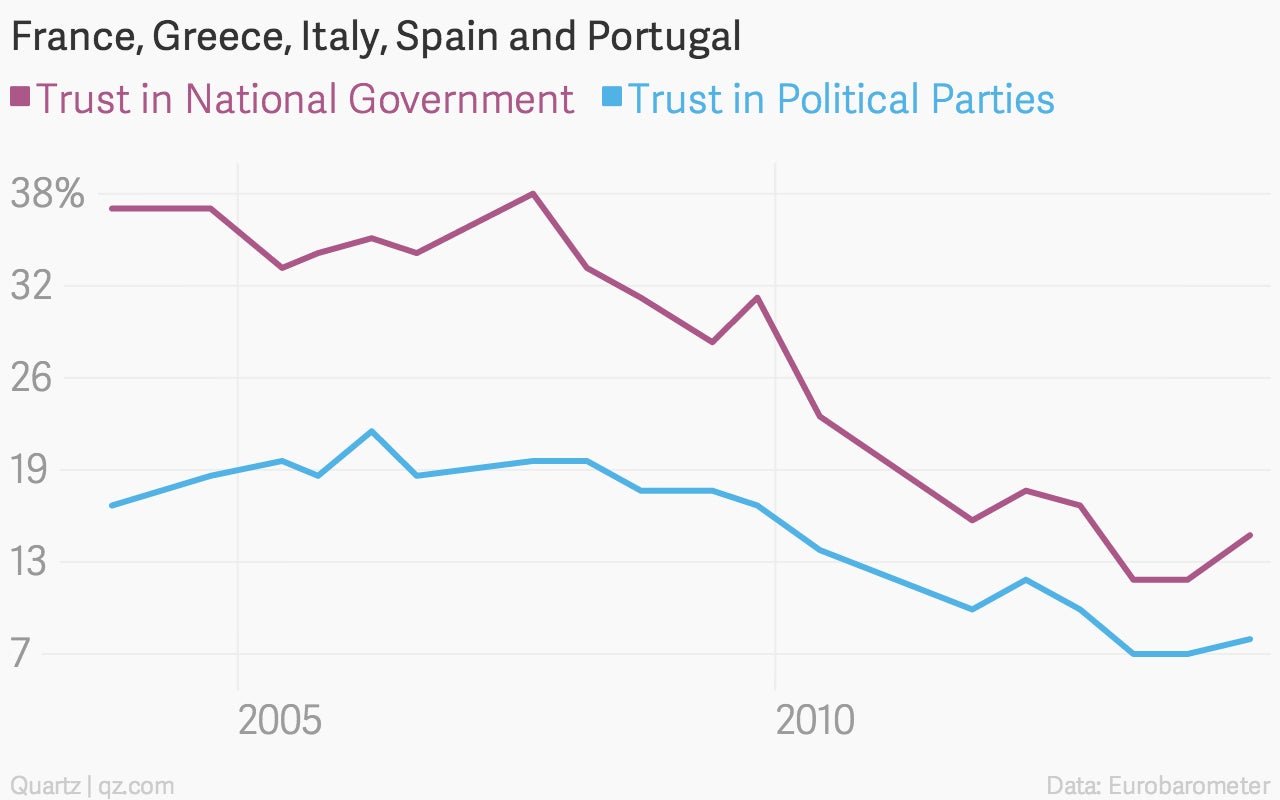

Understandably, people aren’t happy. Syriza came in first in elections for the European Parliament last May, and polls predict that it will win the largest number of seats today.

The political parties that backed austerity point to a return to growth in Greek GDP and the first annual current account surplus in its history as a sign that Greece is on the right path—but for many voters, this feels like too little, too late.

Will Greece leave the euro?

Probably not. But you never know.

Tsipras has toned down his rhetoric since the heady days of the second bailout. He has abandoned talk of leaving the euro that led Der Spiegel in 2012 to label Tsipras among the most dangerous men in Europe. But still, he now wants to tear up the bailout agreement and write off Greece’s enormous mountain of debt, which reached a whopping 175% of GDP in 2013.

Tsipras has even appealed to Germans directly to tell them that they have no choice but to write it off: “Let me be frank. Greece’s debt is currently unsustainable and will never be serviced, especially while Greece is being subjected to continuous fiscal waterboarding.”

This face-off could still lead to a euro exit—the implied threat is that a Syriza-led Greece will default on its debt if its lenders do not forgive its debt mountain and loosen the grip of austerity. Germany—the biggest creditor to the rest of the euro zone—has said this won’t happen.

But Germany has also quietly signaled that it is calm about a Syriza victory and that the euro could cope with a “Grexit” without causing the whole currency to collapse. Add to this that the European Central Bank launched a huge program of quantitative easing last week and many feel that the financial markets can cope with the new, more radical Greece.

Still, any real moves by Tsipras toward an exit from the euro would cause all sorts of panic—partially because there is no official way to leave the euro without leaving the whole European Union.

Also, Syriza is unlikely to win an outright majority, polls suggest, and will need to form a coalition to govern. The most likely ally is a centrist party, which is likely rein in the new government from any real brinkmanship. Still, there are fears that backing away from its more radical policies could lead to a schism within Syriza itself.

What is next for Europe?

The election and the victory of the radical left in Greece could have important knock-on effects for the rest of Europe.

There are national elections to be held later this year in Portugal and Spain—the former has been bailed out, as has the latter’s banking system—and the rise of Syriza could lead to significant gains for the left. In Portugal, the Socialist Party has raised the issue of debt relief and this could accelerate if the far left starts to gain traction from bringing up the issue.

In Spain, the rise of the far-left Podemos party has mirrored that of Syriza and their leaders are close friends. How the Greek leftists perform in government will likely be closely watched Spanish voters.

“A scenario where a Syriza-led government leads to economic and political volatility could limit the appeal of Podemos among undecided voters and constrain the growth potential of the new party,” says Antonio Barroso, an analyst at the consulting firm Teneo Intelligence.

In France, the far-right National Front is even rooting for a Syriza victory to give a further boost to its anti-euro platform. Throughout Europe, in fact, all eyes will be on Tsipras after today.