Nigeria’s giving Muhammadu Buhari—an ex-military dictator—what he’s always wanted: A chance

On the last day of 1983, Nigerians woke up to find their democratically elected government gone. Major general Muhummadu Buhari declared the army had become “deeply concerned” about the conditions under which ordinary Nigerians were living.

On the last day of 1983, Nigerians woke up to find their democratically elected government gone. Major general Muhummadu Buhari declared the army had become “deeply concerned” about the conditions under which ordinary Nigerians were living.

That was Buhari’s introduction to the vast majority of Nigerians. Today, 32 years later, he’s trying to make it where he’s failed at least four times: Winning a free and fair election over a sitting Nigerian president.

This time is different.

Nigerians, already numb to rampant corruption from some quarters within the government of president Goodluck Jonathan, have finally run out of patience with what appears to be the mishandling of growing danger of Islamic insurgents Boko Haram, particularly in the northeast region of the country. And what was once Buhari’s greatest liability—he’s an old military hand in a country teeming with youthful ambition—might be his biggest asset in the run-up to Feb. 14 elections.

“This is the first time an opposition party with a diverse national support base has taken on an incumbent party: it is the end of a long period of elite pacts in national politics,” pronounces the well-respected analyst newsletter, Africa Confidential.

“Old soldiers never die…”

Nigerians were on the streets in celebration when Buhari took over. Just 15 months later, they were on the streets in celebration again—as Buhari himself was overthrown in a coup by general Ibrahim Babaginda. He had overseen one of the country’s least popular and repressive regimes with a string of human rights abuses and a shutdown of press freedom.

That both fuels the appeal and concern from the types of Nigerians who desperately want a change but have been around long enough to remember the wisdom of general Douglas MacArthur: “Old soldiers never die…”

Buhari, a Fulani Muslim from Daura, Katsina, in Nigeria’s north, is 72 now. He appears to have mellowed with age and with each attempt (2003, 2007, 2011 and 2015) tries harder to persuade ordinary Nigerians to trust him with the leadership of Africa’s biggest economy. ”He’s wildly popular among the northern youth where he’s seen someone who stands up for Muslim conservative values and has a strong stance against corruption,” says Roddy Barclay, senior analyst at Control Risks, a risk consultancy firm.

Buhari joined the army straight out of school and received military training in Nigeria, UK, and the US. As well as seeing action during the Nigeria’s Biafran war between 1966 and 1970, he was involved in each of the country’s key military coups and countercoups between 1966 and 1983. He also rose up the ranks of military governments that ran Nigeria in the 1970s, including being the military administrator of the northeast region of Nigeria where Boko Haram currently reigns over various patches.

Hard man

Now, as leader of the coalition opposition party All Progressives Congress, he has promised to once again rid Nigeria of rampant corruption. In the last few years of Jonathan’s government, there have been several stories of misappropriated funds with billions of dollars disappearing.

But Buhari must manage expectations.

“Nigerians are realistic enough to know, from their history, that promising to “stamp out” corruption in Nigeria is a classic example of overselling,” writes popular Nigerian blogger Tolu Ogunlesi.

I am appealing to you: the damage to this country is great. The level of unemployment and insecurity is intolerable, worsened by corruption.

— Muhammadu Buhari (@ThisIsBuhari) January 19, 2015

Perhaps for those who might have forgotten, or perhaps to color the perception of his time in office, a controversial documentary “The Real Buhari” was aired on TV this week in Nigeria (naturally it was slammed by Buhari’s camp).

But the “hard man” image is not a bad one to have at this particular time in Nigeria’s history. For one thing, demographics are in Buhari’s favor. Nearly 60% of Nigeria’s population is under 30, which means the more unsavory aspects of his 15 months in power some 30 years ago, have faded with time.

Halting Boko Haram

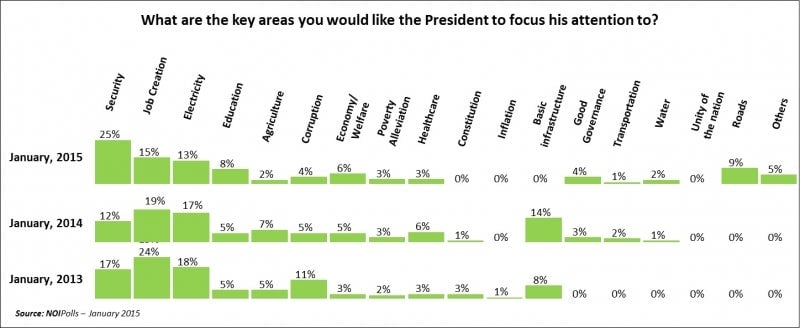

Even though the Boko Haram insurgency started in 2008 in the northeast region of the country, with some 20,000 fatalities in the last five years, it is only in the last year and especially in the last couple of months that a tipping point has been reached. The tide started turning with the slow response by the Jonathan government to the high-profile kidnapping of more than 200 schoolgirls in Chibok back in April and in recent weeks the attack on Baga, which Amnesty International reported claimed up to 2,000 lives. A survey at the end of year saw security jump to the top of the Nigerians’ agenda ahead of job creation for the first time in three years.

Buhari is widely seen as a strict, disciplined, and strong leader at a time when Jonathan has appeared at times to want to avoid talking about Boko Haram. The fact that he is a Muslim northerner will undoubtedly help win votes in those parts of the country where they have started to believe, perhaps unfairly, that Jonathan, a Christian from Nigeria’s oil-rich southeast, doesn’t care enough about their troubles. In the last year, the gap between the candidates has “closed spectacularly,” says Control Risks’ Barclay.

“It’s still a close election but the trend is in [Buhari’s] favor,” says Mark Schroeder, vice president of Africa Analysis, Stratfor, a global intelligence and advisory firm.

I again call on security agencies to promptly arrest and prosecute all those found guilty of violence in any form. This is an urgent duty.

— Muhammadu Buhari (@ThisIsBuhari) January 24, 2015

“It’s the economy, General”

The challenge for a Buhari presidency will be when ordinary Nigerians again focus on their usual pet issues: the economy and job creation. While reliable statistics are not easily available, the Nigerian unemployment rate is widely believed to be more than 20%; it was reportedly 23.9% in 2012.

There are other obstacles: Nigeria’s oil-led economy starts to roil from a 50% plunge in oil prices and the Nigerian currency has dropped through the psychological barrier of 200 Naira to $1 to around 208 in parallel markets last week. Buhari’s handling of the economy in 1984-85 was arguably as big a reason for his being overthrown in 1985 as was his poor human rights record.

Yet even when the Nigerian economy was growing rapidly driven by oil at well over $100 a barrel, the ordinary Nigerian did not feel the impact due to mismanagement. “The gulf between the government elite and the ordinary man on the street is so vast,” Schroeder says.

Now that oil is under $50 a barrel, a focused leadership that eschews much of the wasteful habits of Nigeria’s usual leaders will be more essential than ever. The question is whether Buhari can be the leader that breaks that trend once and for all.