Afghan carpet weavers are putting drones on their rugs

When it comes to what to depict on rugs, Afghan weavers traditionally turn to what’s most familiar. So in the 1980s, when the Mujahedeen were fighting back the Soviet occupation, some local weavers abandoned flowers and water jugs to illustrate what their days consisted of back then: war.

When it comes to what to depict on rugs, Afghan weavers traditionally turn to what’s most familiar. So in the 1980s, when the Mujahedeen were fighting back the Soviet occupation, some local weavers abandoned flowers and water jugs to illustrate what their days consisted of back then: war.

Tanks, helicopters, Kalashnikovs, hand grenades and bazookas started creeping into the centuries-old tradition, either as elements of a landscape or as icons in a pattern. “My favorite one is an old Beluch style one,” says 49-year-old US entrepreneur Kevin Sudeith, “The design dates back to the 19th century but it has two helicopters and two tanks at each end of the rug.”

In 1996, Sudeith discovered one of the war rugs in the house of an Italian architect and decided to start collecting them. Shortly after, he was dealing them, both online and in flea markets around New York for prices ranging from a few hundreds to several thousand US dollars each.

After 9/11, he thought his business was going to disappear. Surprisingly, a renewed interest in Afghanistan pushed the orders up, especially following the arrival on the market of a new set of rugs, depicting the attacks to the World Trade Center. In one of them, the misspelled caption “The teroris were nhe American“ caused controversy in the US, as it seemed to imply that the rugs’ makers were celebrating the attack.

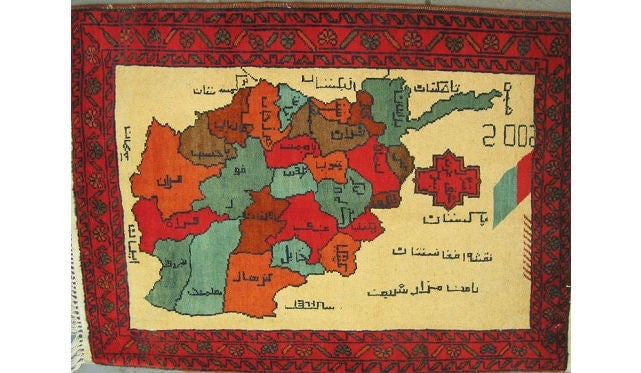

More rugs produced in that period featured F16 fighter jets, Abrams tanks and maps of Tora Bora, confirming that the iconography of Soviet occupation had been replaced by that of the United States military. The majority of weavers, says Sudeith, were Afghan refugees living in Pakistan who, regardless of their former careers back in Afghanistan, had become “a sort of captive labor force.”

This may be the dark side of war rugs. Although Afghan weavers are traditionally women, Western collectors and dealers only deal with intermediaries, so it’s difficult to verify who actually makes the rugs, and under what circumstances. The US Department of Labor, for example, lists those made in Afghanistan and Pakistan among the crafts that may involve child and forced labor. Sudeith himself never met the Afghan family that makes most of his rugs. “The brass ring for war rug people is to speak with weavers and hear their stories and motivations,” he confesses, “So far, it’s been impossible.”

After the Taliban was removed from Kabul, millions of Afghans were repatriated, causing a new shift in the rugs business: on one hand, most production followed the weavers back to Afghanistan; on the other hand, the rugs that had been woven in Pakistan became rare and therefore more valuable. These, says Sudeith, were the best years for business.

Recently he has noticed that the mysterious weavers seem somehow savvier, more attuned to demands of the market. “If I write a blog post about a particular rug,” says Sudeith, “Eighteen months later contemporary, handmade versions of it will appear.”

“A super subtle drone war rug. Dated 2014. Vegetable dye, super quality wool. Totally unique and timely piece.” In December 2014, Sudeith posted online images of a new set of drone-themed rugs, selling for a few hundred dollars. He calls them the product of a “collaborative process” with a family in Pakistan, based on designs that have previously emerged in the market.

Considering the ongoing program of US drone strikes in Pakistan, these new patterns are likely to pick up as a popular theme among war rugs creators and their collectors. According to an October 2014 update from the UK-based Bureau of Investigative Journalism, more than 1,000 civilians have been killed in Pakistan by drone strikes over the past 10 years, around one-fifth of them children.

This post originally appeared at Colors Magazine. Photos by Kevin Sudeith, courtesy of Warrug.com.