Iceland is melting so fast, it’s literally popping off the planet

This item has been corrected.

This item has been corrected.

Iceland is rising. Or, more precisely, the island’s “ice” part is shrinking, causing the “land” part to rebound from the Earth’s crust—a process that’s happening at a pace much faster than scientists had previously realized. In fact, its glaciers are melting so swiftly that parts of Iceland are rising as much as 1.4 inches (35mm) a year.

That’s according to research just published (paywall) by a team led by scientists from the University of Arizona. The study is the first to directly link the Earth’s accelerating uplift with quickening pace of glacial thaw. As this process intensifies, the scientists warn, it risks upping the frequency of volcanic eruptions.

What’s new here isn’t the science itself, exactly. Glaciers are so heavy that they weigh down the earth that they cover. A while back, geologists discovered that where huge chunks of ice are thinning, the earth beneath them starts rebounding. And evidence suggests that higher latitudes are warming faster than the global average.

What scientists haven’t understood, though, is whether the ground’s bounce-back comes from glaciers that melted long ago—or whether this is due to recent climate change.

In Iceland, at least, global warming is the culprit, according to Richard Bennett, a UA associate professor of geosciences. He and his team figured this out by attaching GPS receivers to rocks all over Iceland, and then calculating how far the rocks traveled over time.

“What we’re observing is a climatically induced change in the Earth’s surface,” he says.

Even more worryingly, this change is happening way faster than previous research suggested. If melting continues at its current pace, by around 2025, some parts of Iceland will be rising at a rate of 1.6 inches a year.

There’s a downside to all of this—and it’s a big one. The thinning of the glaciers reduces the pressure on the rocks beneath, as Kathleen Compton, a UA geosciences doctoral candidate who led the research, told Time, citing the work of other researchers. The danger for Iceland is that high heat content at lower pressure creates conditions more likely to melt the rising mantle rocks—feeding more magma to volcano systems.

Bennett points out that the last time its glaciers got skimpy—about 12,000 years ago—Iceland’s volcanic activity leapt thirtyfold in some parts of the island.

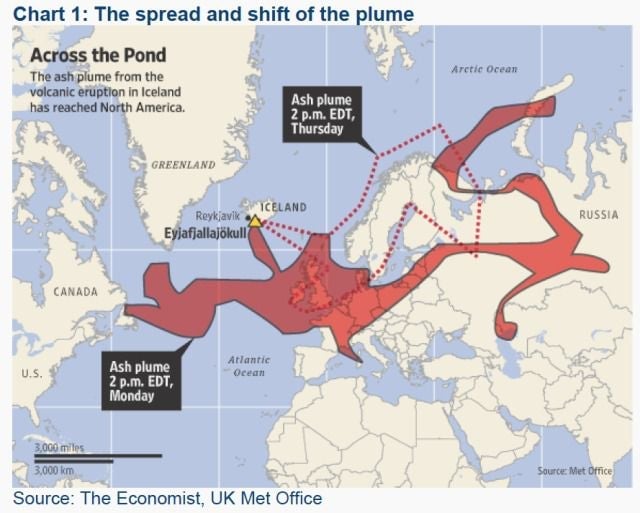

That’s grim news not just for Icelanders, but for everyone. In 2010, the eruption of Eyjafjallajökull cost the global economy an estimated $5 billion. And while Bárðarbunga’s rumblings in August 2014 proved less eventful, it’s still erupting, and has set off another of the region’s volcanoes. More ominously still, the eruption of Laki in the 1780s killed a quarter of Iceland’s population, wiped out 23,000 Brits, set off famine in Egypt, and may have helped spark the French Revolution.

Correction (January 30, 2015, 1pm EST): A previous version of this article misstated the yearly rate of uplift in some parts of Iceland by 2025. The correct number is 1.6 inches a year.