The geometry of the fiscal cliff talks: First, do no harm

Last week, US President Barack Obama sent Treasury Secretary Tim Geithner with the administration’s first offer in talks to stall out America’s austerity trigger. Now, the opposition Republicans have sent a letter (pdf) to Obama detailing their disappointment and, eventually, their counter-offer: A very literal compromise plan floated by fiscal guru Erskine Bowles during an appearance before one of America’s innumerable debt committees that split the difference between the two parties once-current proposals. The difference an election makes is that the Republicans are leading with last year’s compromise while Obama makes a big demand.

Any negotiation starts with two points

Last week, US President Barack Obama sent Treasury Secretary Tim Geithner with the administration’s first offer in talks to stall out America’s austerity trigger. Now, the opposition Republicans have sent a letter (pdf) to Obama detailing their disappointment and, eventually, their counter-offer: A very literal compromise plan floated by fiscal guru Erskine Bowles during an appearance before one of America’s innumerable debt committees that split the difference between the two parties once-current proposals. The difference an election makes is that the Republicans are leading with last year’s compromise while Obama makes a big demand.

What’s between the two points?

The biggest obstacle isn’t necessarily the magnitude of the numbers, but the mechanism for raising between $800 trillion and $1.6 trillion in new tax revenue. Obama wants to allow the Bush tax cuts for the wealthy to expire, and limit or eliminate a host of deductions. House Speaker John Boehner wants to eliminate the deductions. This could work—if most rates stayed the same or were assumed to increase to the levels of the 1990s, the Obama administration has endorsed tax reform. But in his letter, Boehner has said he now wants to lower rates while doing this kind of base-broadening tax reform, which gets you dangerously close to the problem Mitt Romney had during the election year: His combination of tax priorities became mathematically impossible.

Obama made his position on this front clear in a Twitter chat promoting his plan:

This is one case where Obama’s insistence on limiting tax increases on the middle class becomes nearly as problematic as the GOP’s refusal to raise taxes on the wealthy: Deductions on home mortgages and health insurance, while wildly popular, distort economic decisions without adding economy-wide benefits. Spreading the burden of tax increases as widely as possible is a good idea—but that’s what negotiators are going to be talking about.

That, and how to cut Medicare spending. Republicans want to raise the age of Medicare eligibility, but the Obama administration is under pressure from their base to draw a red line around the age issue and focus on subtler cuts—eliminating corporate subsidies and lowering payments to nursing homes.

A reminder: A line is the shortest distance between two points

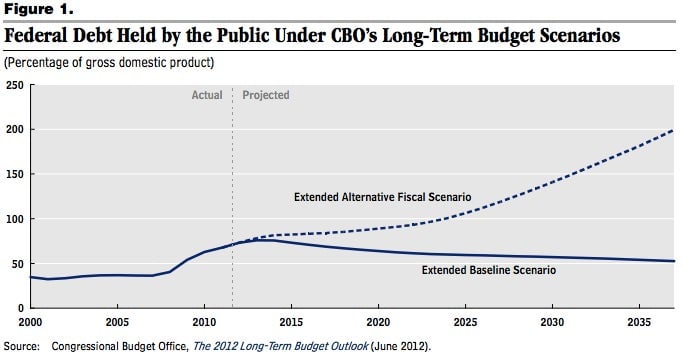

It’s worth remembering that the goals of the deal can be reasonably modest because, rhetoric to the contrary, the goal of the talks are to preserve economic growth, not reduce the debt. The chart above shows what US debt looks like if the government keeps doing what it’s been doing (the “Extended Alternative Fiscal Scenario”) or if it does nothing, allowing the fiscal cliff to occur and sticking to legally-mandated budget targets. The Congressional Budget Office estimates (pdf) that cutting the deficit just $500 billion in 2020 will stabilize the debt at its present levels. The magnitude of consolidation under discussion by both parties exceeds that goal, moving close to a point that would begin reducing debt along the same lines as the baseline scenario above.

The takeaway is that if Obama and Boehner need to scale back their fiscal consolidation ambitions to make a deal to cushion the economy from the fiscal cliff—and even adopt some of Obama’s proposed near-term stimulus—they can do it without putting the US on the path to bankruptcy. Doing just enough can be better than trying to do too much, and failing.