Google expands its “web of things” to seven new languages

Google is bringing more robust search results, going well beyond a list of links, to seven new languages: Spanish, French, German, Portugese, Japanese, Russian, and Italian.

Google is bringing more robust search results, going well beyond a list of links, to seven new languages: Spanish, French, German, Portugese, Japanese, Russian, and Italian.

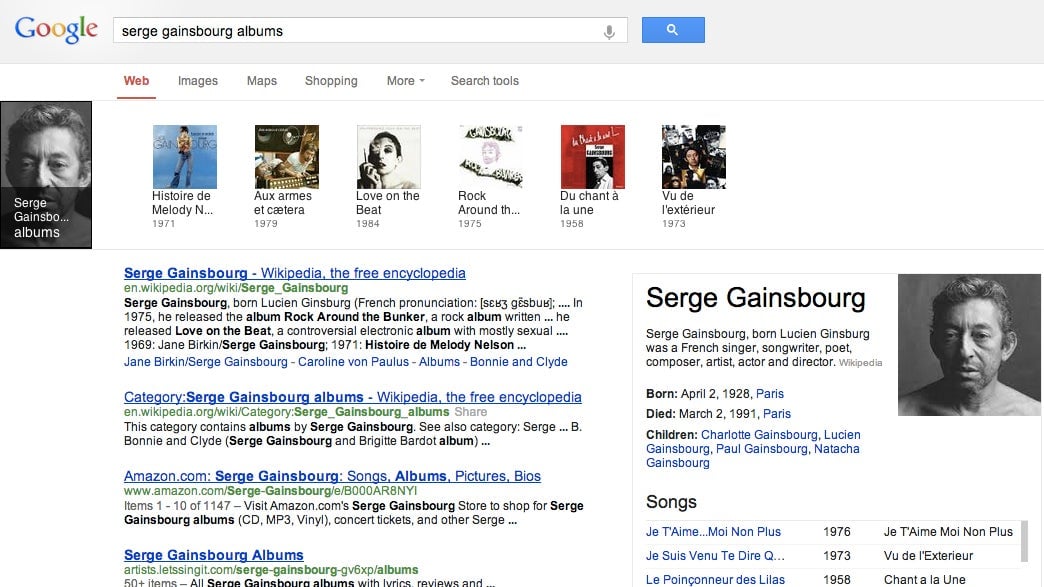

Since August 2012, users of Google’s English-language search engine have had more and more of their search queries answered with images and text that take over the top and right sides of their browser windows, delivering direct answers to queries like “Don DeLillo books” and “Serge Gainsbourg albums.” Now that same capability—a web of “things and not strings,” as Google puts it—is coming to the rest of the world, Google just announced.

That means, for example, that Francophones who search for Serge Gainsbourg will get the same headshot and list of images that English speakers have been seeing for months, all without having to click through to a search result.

Google calls this the “knowledge graph.” The larger significance of this announcement is that Google is moving away from “dumb” search, which only scours the web for “strings,” computer-science jargon for the strings of letters that comprise words. Instead, Google would like to create a search engine that knows that Benjamin Franklin was a person who lived in Philadelphia and has countless connections to other “things” in Google’s search database.

Google’s video explanation of the knowledge graph is a good way to get a grip on what they’re trying to do:

And here’s how the company itself describes it.

Take a query like [taj mahal]. For more than four decades, search has essentially been about matching keywords to queries. To a search engine the words [taj mahal] have been just that—two words.

But we all know that [taj mahal] has a much richer meaning. You might think of one of the world’s most beautiful monuments, or a Grammy Award-winning musician, or possibly even a casino in Atlantic City, NJ. Or, depending on when you last ate, the nearest Indian restaurant. It’s why we’ve been working on an intelligent model—in geek-speak, a “graph”—that understands real-world entities and their relationships to one another: things, not strings.

Building a knowledge graph in any language is non-trivial. A Google spokesperson I talked to said today’s release has been in the works for years, since before Google had even acquired Metaweb, the company whose workers has been building these graphs.

As Google noted in a blog post on the addition of new languages to Knowledge Graph,

This is more than just translation. The Knowledge Graph needs to account for different meanings of the same word — “football” means something quite different in the U.S. than in Europe. It also needs to recognize what’s most important in a particular region. The graph now covers 570 million entities, 18 billion facts and connections, and about three times as many queries globally as when we first launched it.

On the one hand, knowledge graphs fit perfectly with Google’s mission to “organize the world’s information.” On the other hand, they seem like another way to keep users on Google’s search engine—and expose them to advertising—for longer periods of time. Pundits have often speculated about how much money Wikipedia could make if it ran ads. In as much as Google’s knowledge graph powers a Wikipedia-like experience, it feels a little like an attempt to find out.