This plan to run bike paths through London underground tunnels is ridiculous

It’s a seductive vision: re-use existing infrastructure, in this case London’s disused Tube tunnels, to solve a problem–the dangerous interplay of vehicles, cycles and pedestrians on the streets above.

It’s a seductive vision: re-use existing infrastructure, in this case London’s disused Tube tunnels, to solve a problem–the dangerous interplay of vehicles, cycles and pedestrians on the streets above.

The plan, from architectural firm Gensler, won a prize this week for best conceptual project at the London Planning Awards (note: “conceptual”). The London Underline, as it is called, would create not only walking and cycle paths, but underground shops, cafes and art spaces.

(But wait! Isn’t one of thing best things about cycling the fact that it’s outdoors? That cyclists don’t have to use the Tube? Shhhh.)

It’s not the first such scheme. In 2014, a plan was floated for a “Deckway” which would see about five miles of cycle path built along the Thames—above the water, that is, not beside it. The projected cost was around £600 million ($972 million). The firm of architect Norman Foster came up with SkyCycle, a different kind of deck that would run above train lines.

All the plans have merits. But they’re also all expensive, building-heavy and—in such a densely populated city with so many pulls on its finances—unlikely to happen.

They also, perhaps, distract attention from more fundamental problems on the city’s roads: including a vicious turf war between drivers and cyclists.

This week Transport for London (TfL) confirmed plans to build more “cycle superhighways”—designated routes that use quieter streets for cyclists, and separate their paths from traffic with a curb on heavily used roads. The agency aims to double cycling over the next ten years, and these plans will cost £160 million.

Even off the actual streets, the relationship between drivers and cyclists in the city is deeply fraught (as they have been in other cities around the world trying to become more bike-friendly). A TfL board member was this week quoted as saying the greatest dangers to cyclists came from their own actions. The general secretary of the Licensed Taxi Drivers’ Association said in a radio interview that fanatical cyclists were a bit like the “ISIS of London.”

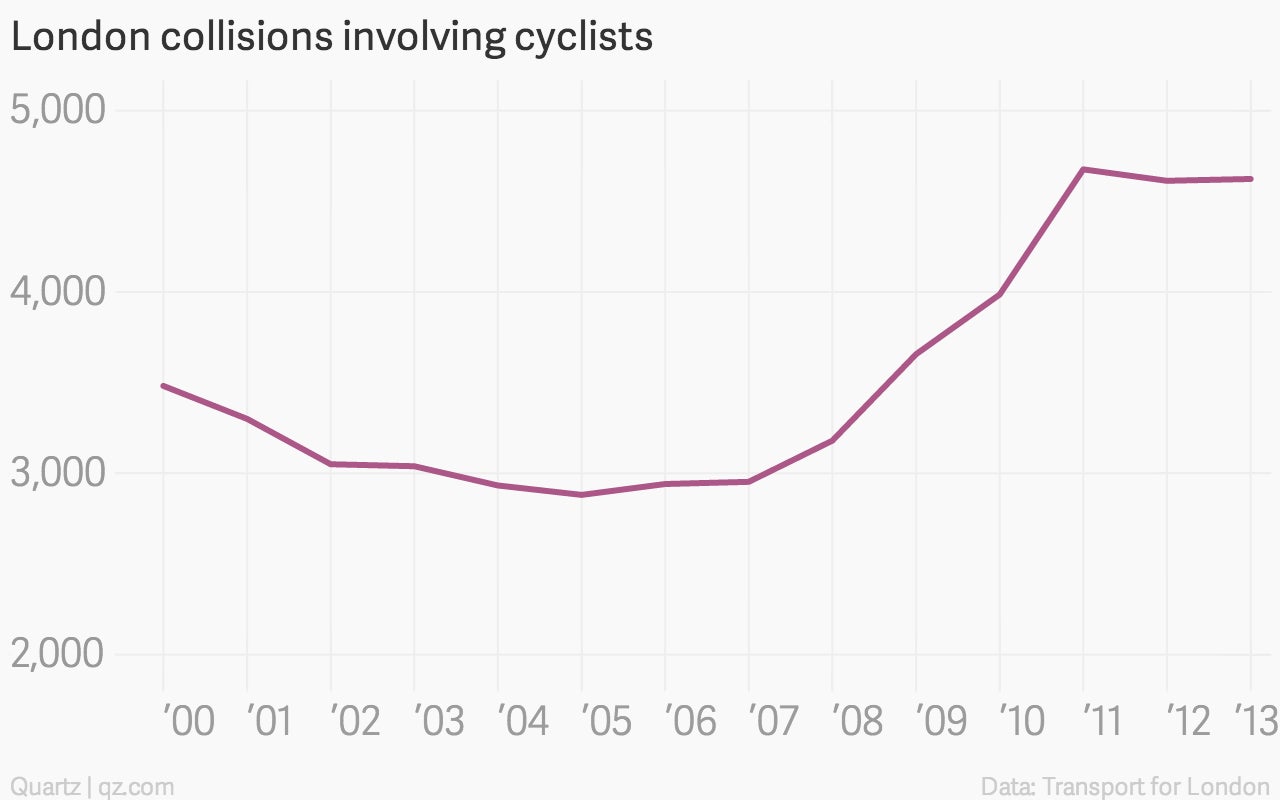

In truth, London’s streets are too crowded. The introduction of a “congestion charge” in 2003 that forces private drivers to pay £11.50 to enter the city center alleviated some traffic, but it’s still heavy. A city cycle-hire scheme that facilitates the journeys of business people and tourists (often without cycling experience or helmets) put 10,000 more bikes on the road in 2010.

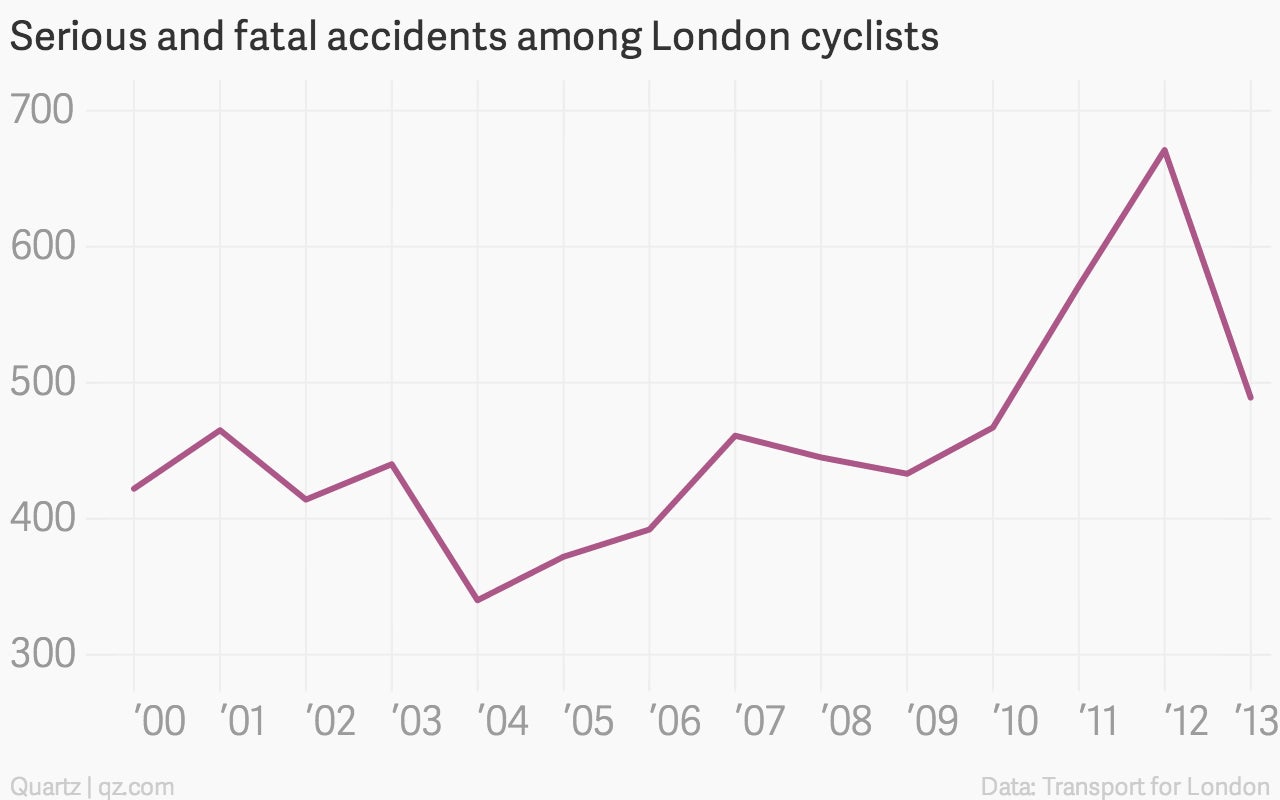

Meanwhile, when cars, trucks, buses and taxis kill and maim, cyclists complain that most drivers aren’t held to account. Between 2010 and 2013 there was an average of 15.6 deaths per year in London, and 440 serious injuries to cyclists. This includes a sharp drop in injuries in 2013, which TfL linked to better all-round road safety that year.

That record doesn’t make it the worst city for cycling in the world (it was comparable last year to New York). But its safety record certainly isn’t one of the best.

Brokering a peace between cabbies, truck drivers, cycle couriers and all the other road users should be a priority for the London authorities. This—as well as improving existing road layout—might do more to improve these statistics than complex design concepts, and do it quicker.