Hurricane Sandy turned a New York subway station into a petri dish of Antarctic bacteria

On Oct. 29, 2012, Hurricane Sandy sent a tidal surge roaring through Lower Manhattan, pouring millions of gallons of seawater into South Ferry Station. Metro transit authorities who inspected the subway station encountered what they called “a large fish tank.” The spillover from New York Bay had filled the tunnels with water 80 ft. (24 m) deep.

On Oct. 29, 2012, Hurricane Sandy sent a tidal surge roaring through Lower Manhattan, pouring millions of gallons of seawater into South Ferry Station. Metro transit authorities who inspected the subway station encountered what they called “a large fish tank.” The spillover from New York Bay had filled the tunnels with water 80 ft. (24 m) deep.

Nearly two and a half years later, South Ferry Station has long since been drained. But Hurricane Sandy’s imprint remains—on a microscopic level. That’s according to a study just published in Cell Systems, which its authors have used to create PathoMap, a cartographic sketch of the New York subway system’s microorganism populations.

While the unseen world that teems around New York commuters vary slightly from neighborhood to neighborhood—see this Wall Street Journal map for specific stations—they’re all roughly similar. Not the still-shuttered tunnels of South Ferry Station, though.

“If you saw [the station’s bacterial colony] you’d think, ‘Oh, this looks like a fish—it looks like something you’d find in a fish,'” says the study’s lead researcher, Christopher Mason, an assistant professor at Weill Cornell Medical College. “And some are just associated with cold marine environments.”

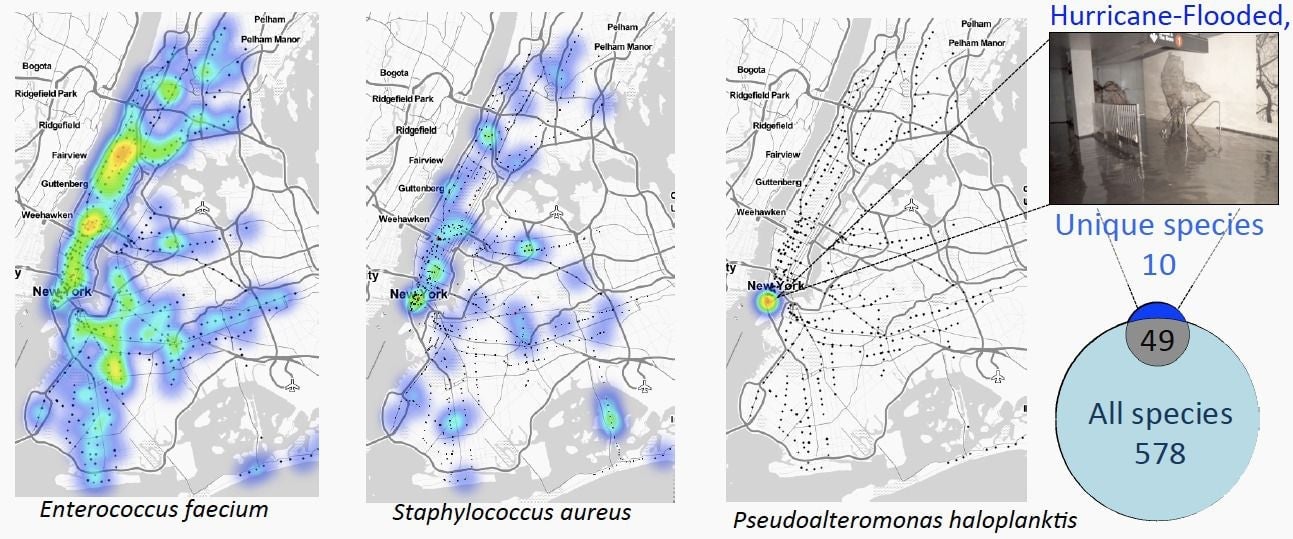

Several of South Ferry Station’s unique bacteria hail from polar waters or the North Sea—like Pseudoalteromonas haloplanktis, for instance. This map compares the concentrations of three bacteria. The first two maps show the prevalence of the human gut bacteria Enterococcus faecium and Staphylococcus aureus, which colonizes people’s skin. P. haloplanktis, however, tends to thrive in chilly Antarctic waters.

In fact, the bacteria in South Ferry Station aren’t common to New York coastal water at all. After comparing the station’s microbiome with that of Brooklyn’s Gowanus Canal, the researchers found that the majority of samples from each site differed starkly. (Gowanus was also packed with industrial bacteria that likely relate to its severe pollution problems in the past).

The difference almost certainly came down to what Mason calls the “molecular echo” of Hurricane Sandy, whose tidal storm surge transplanted a colony of fishy, polar sea bugs.

This is a phenomenon scientists have never before demonstrated—proof that, as Mason puts it, “an environmental disaster can be rendered onto the surfaces of a given area.”

“That alone has never been shown before—but especially in an urban environment,” he says. “The key question is how long it will last.”

Probably not much longer. The now-closed parts of South Ferry Station are slated to open up again in 2016. Then the rigorous off-hours scrubdown will zap the microscopic post-Sandy squatters, clearing the way for new colonies to form each morning, as commuters smear surfaces with their own bacteria. In time, South Ferry Station’s microbiome will probably look once again like it did on Oct. 28, 2012, teeming with bugs that prefer human hosts to fish.