Inside the lab where scientists are 3D-printing a real working trachea

3D printing has been used to make fast food, jewelry, electric guitars, and tiny versions of ourselves. But one area where it shows particular promise is medicine. Quartz visited a lab where a research team has figured out how to use a 3D printer that sells for $2,500 to make replacement body parts out of living cells.

3D printing has been used to make fast food, jewelry, electric guitars, and tiny versions of ourselves. But one area where it shows particular promise is medicine. Quartz visited a lab where a research team has figured out how to use a 3D printer that sells for $2,500 to make replacement body parts out of living cells.

Hidden away in a windowless section of the Feinstein Institute at North Shore-LIJ Hospital in Manhasset, New York, Todd Goldstein is working on replacing damaged sections of the trachea—the pipe of cartilage that connects the lungs to the throat. Goldstein, an investigator at Feinstein who is studying for a PhD in molecular medicine, is part of a research group working primarily in orthopedics, the treatment of bone and muscle problems.

Goldstein and his team are fixers. On the day Quartz visited, they were working on a project involving very small samples that were getting blown around by the room’s air-conditioning. The building’s administration had told them that they couldn’t make any changes to the air-conditioner vents. So they took binder clips and hung sheets from the ceiling to keep the airflow away from their work.

This same lateral thinking is what brought a group of throat doctors to the team. The trachea can get damaged by tumors, during intubation—when a plastic tube is fed down the trachea to keep the windpipe open during surgery—or in an accident. According to the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, tens of thousands of tracheal procedures take place in the US each year. But repairing or replacing a trachea can be invasive and complicated.

Normally, replacing a trachea requires two surgeries. First, surgeons have to cut a piece of the cartilage connected to a patient’s rib and shape it—by hand—to create a new piece of trachea. Then they have to cut into the patient’s throat and fit the new piece. This is (highly) educated guesswork. If the surgeons’ work is off by a millimeter or two, they have to reshape the trachea while the patient is still lying there anesthetized.

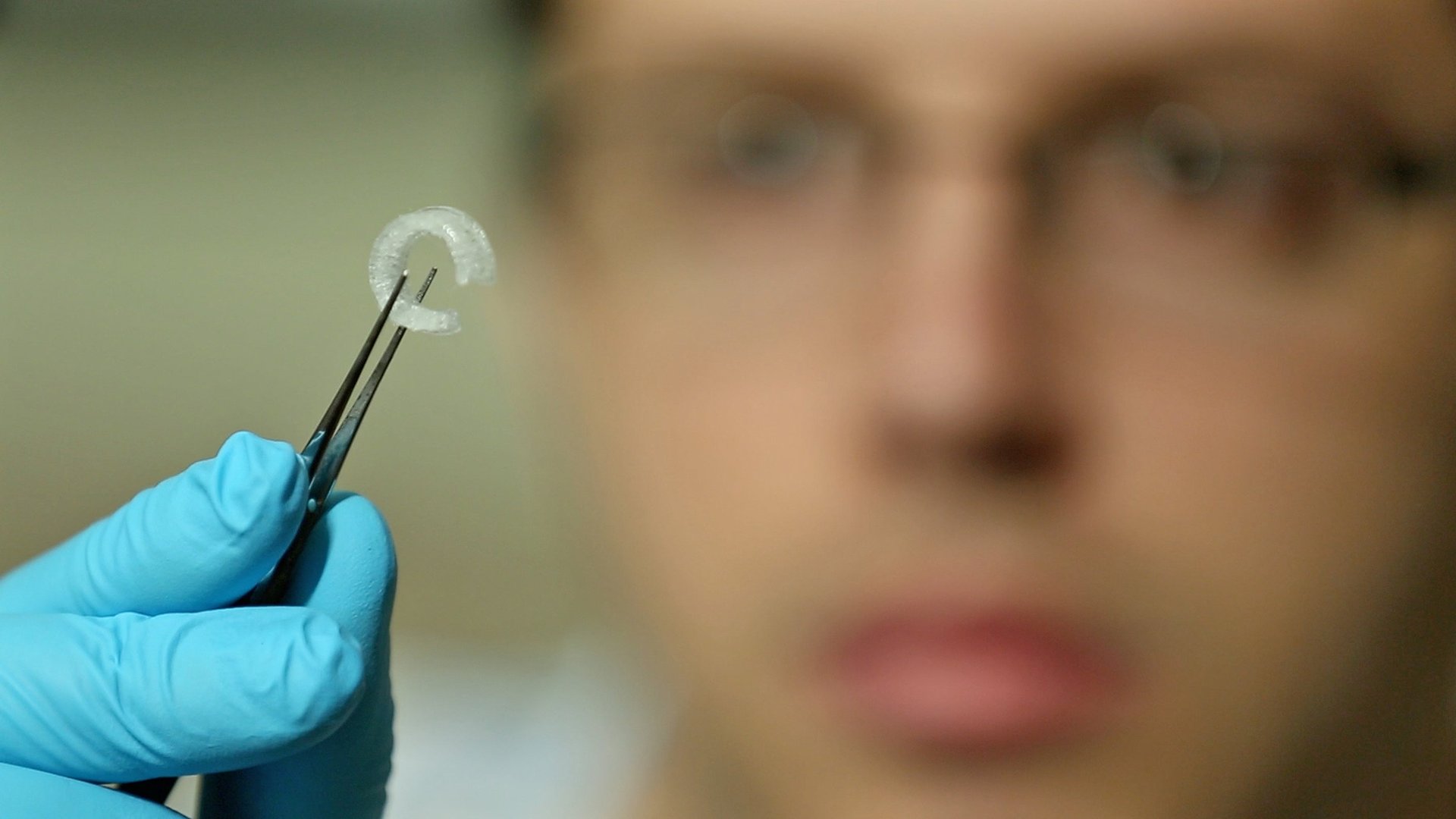

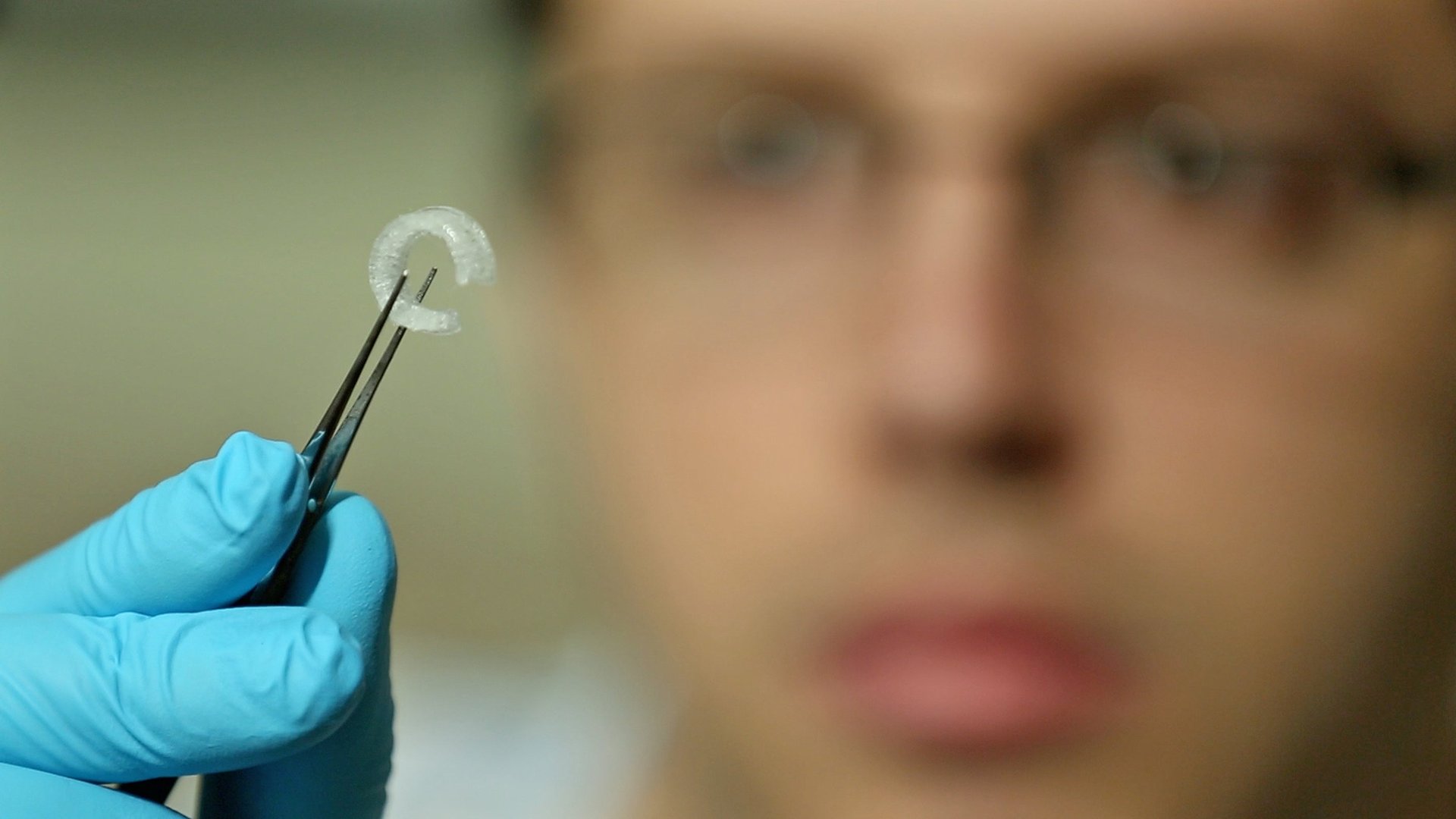

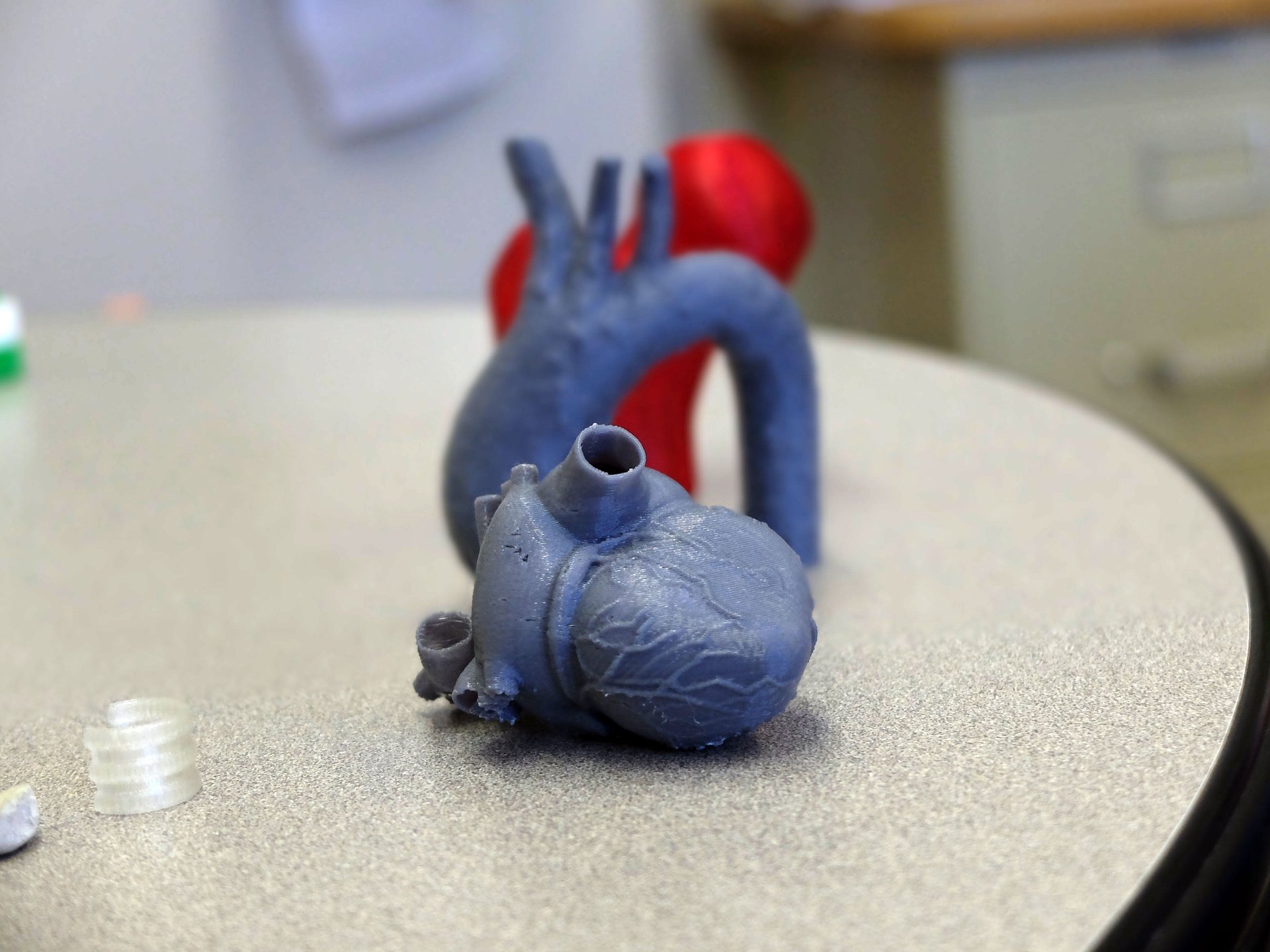

Goldstein tested the principle by asking doctors for detailed three-dimensional CAT scans of an actual patient’s throat. The scans showed which parts of the trachea were damaged and needed replacing. Goldstein could then print out 3D plastic models of replacement parts as many times as necessary, working with surgeons to get the exact right fit. In practice, that would mean surgeons could plan out exactly what needed to be implanted in a patient before making an incision. Once they were happy with the plastic models, the real thing could be printed.

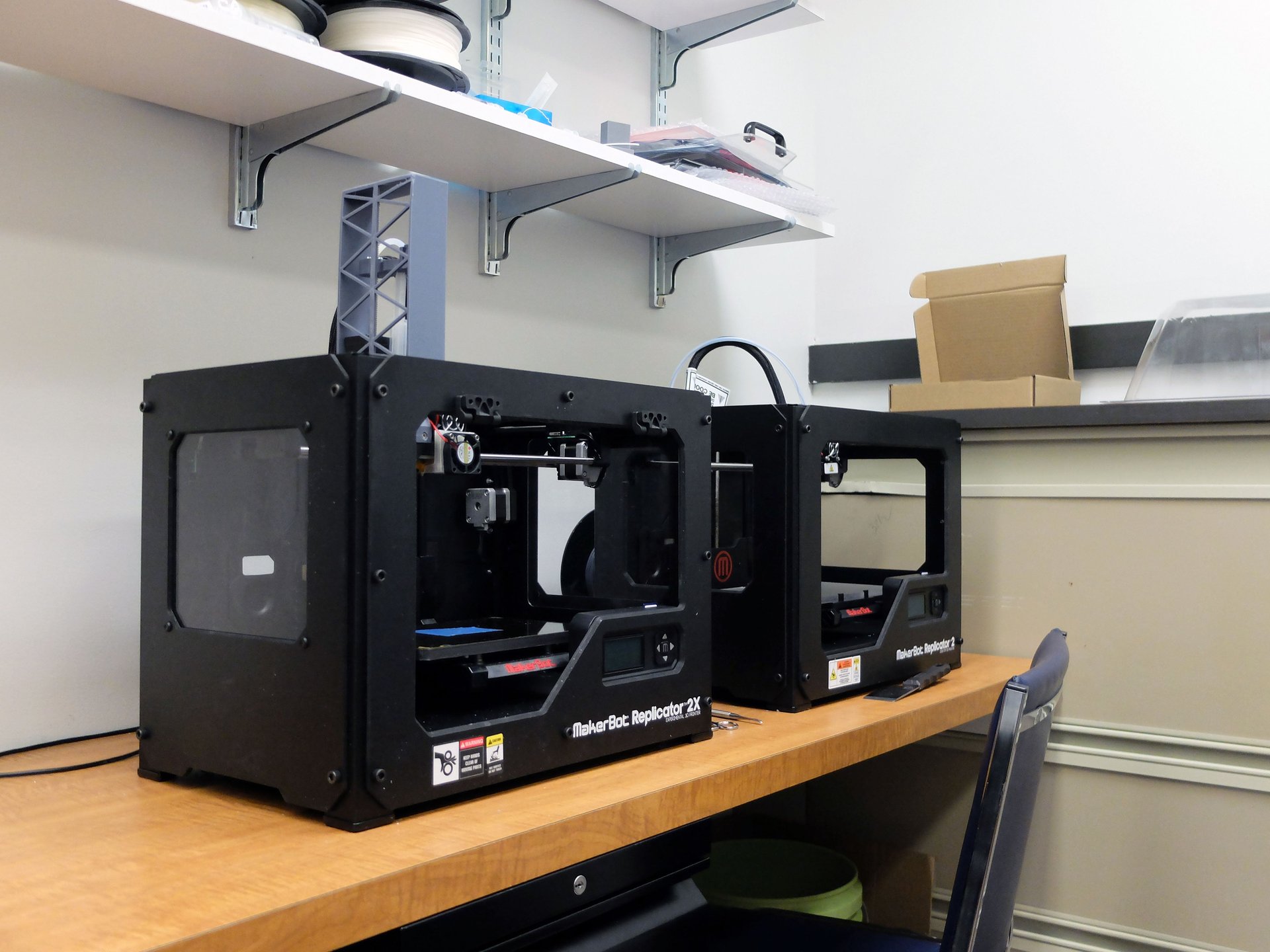

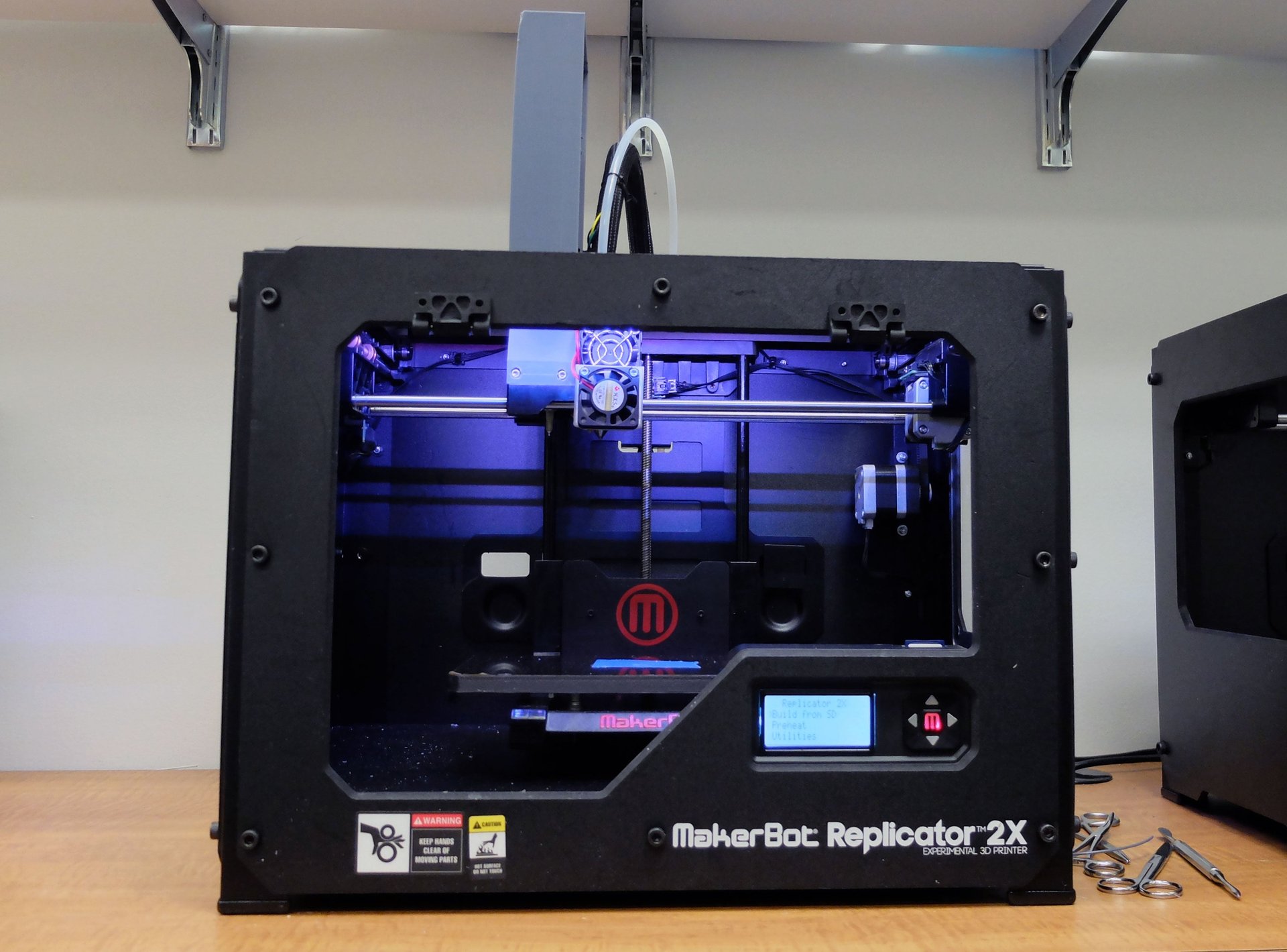

The team’s tools are a pair of MakerBot Replicator 3D printers, which the manufacturer gave the hospital. One is just for printing plastic. Goldstein has modified the other to extrude regular PLA plastic—the filament commonly used in 3D printers—and “bio-ink,” which is a mixture of cartilage cells, nutrients, and collagen, the main protein that holds tissue structures together (it’s also a large component of bones and cartilage). PLA plastic has also been used as part of surgical implants, such as the screws in knee ligament reconstruction. Although the PLA will eventually dissolve over time, it provides a flexible framework around which tracheal cells can form.

Printing a trachea is much like printing any object, although it requires a bit more patience. MakerBot printers use a technique called extrusion printing, which creates objects out of successive thin layers of molten plastic that bind together as the printed object cools. Printing a tracheal replacement requires alternating layers of plastic and bio-ink. That means waiting for each layer of plastic to cool so its heat doesn’t kill the living cells. Goldstein says the plastic models take about five minutes to print but the replacement trachea itself takes several hours.

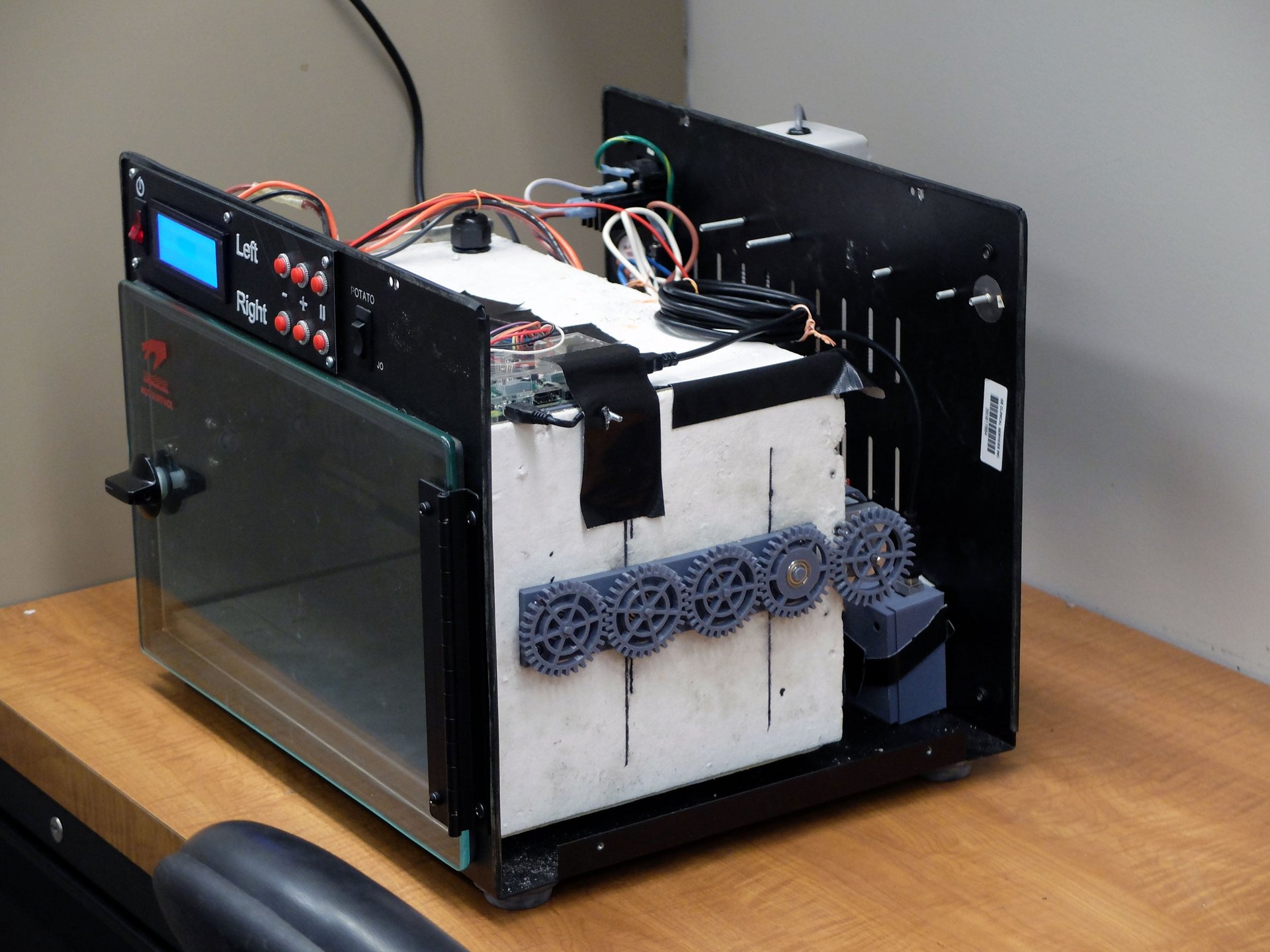

Once the printer has finished the final structure, the trachea-to-be is transferred into a modified incubator, where the cells continue to grow around the plastic. The whole structure would then be inserted by a surgeon into a patient. Goldstein took an old incubator that the institute was going to decommission and is adapting it to grow his tracheae. He 3D-printed new parts—gears, screws, fittings—using models he found on MakerBot’s 3D model repository, the Thingiverse, to make the incubator, as he said, more like a rotisserie oven on the inside, so the cells are warmed evenly. “It looks like a Game Boy now,” Goldstein said.

Goldstein presented his work last month to the Society of Thoracic Surgeons. A representative for the US Food and Drug Administration told Quartz that the administration has not approved any 3D printers for human use, but it has “significant scientific interest in this topic.” It’s uncertain when the first trial of 3D-printed human tissue could happen, but it does seem likely to be a question of if, not when.

In the meantime, Goldstein’s research continues. He said MakerBot has provided him with a new type of filament made primarily of PLA plastic and limestone, which is not yet available to the general public. Limestone is made almost entirely of calcium carbonate, which is also found in bones. While Goldstein couldn’t say how he was using this filament in research, he spoke of a future where doctors could theoretically replace parts of damaged bones with 3D printed materials.