Stack it? Melt it? Dump it in the river? Weighing the options for America’s snowed-in cities

When a city like Boston gets buried in snow, as has occurred in epic proportions this year, there’s more to be done than simply plowing the streets.

When a city like Boston gets buried in snow, as has occurred in epic proportions this year, there’s more to be done than simply plowing the streets.

In Boston, excess snow removed from roadways is typically hauled off to vacant lots known as “snow farms,” which would be better described as snow landfills; these lots turn into dirty dumps packed with salt, sand, oil, and street trash frozen in slush. Then, the snow just sits there, in drifts tens of feet high, until warm weather arrives to melt it.

Only in extreme circumstances, such as this week, when the snow farms get too full and snow is still accumulating on the streets, will the city borrow snow melting machines from Logan Airport to more quickly dispose of the pileups. But in really dire situations (again, this week qualifies) those measures will not be enough—prompting the city to contemplate dumping snow in its waterways.

In New York, standard operating procedure is a bit different. There aren’t any snow farms, but the city’s department of sanitation has 36 snow melters and doesn’t hesitate to use them, according to department spokeswoman Kathy Dawkins.

During the last week of January, when between six and 12 inches of snow fell in Manhattan, protocol dictated a “piling and hauling” operation, with front-end loaders pushing the snow into piles and dump trucks hauling it off to the snow melters. The melters are positioned over sewers, on streets that have been closed off to cars and pedestrians.

One might wonder (and indeed, many have) whether this process is any better than just dumping the snow in a river. But what gets collected in these cities is not virgin snow; it contains a nasty mix of pollutants that generally are best kept out of public waterways.

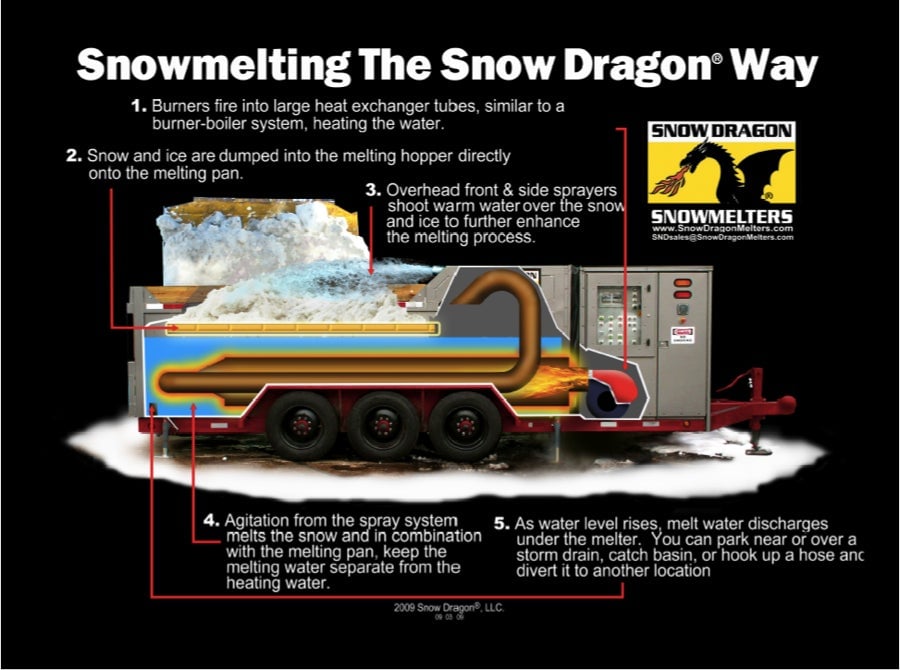

What about the energy and carbon emissions associated with snow-melting machines, though? And what if the melted snow re-freezes before it flows through the sewers? Wouldn’t that make things worse? Quartz called Snow Dragon, one of three snow-melter manufacturers in North America, for answers.

Snow Dragon, headquartered in Wickliffe, Ohio, near Cleveland, has sold more than 90 machines since 2004. Its most popular model, the SND900, retails for $226,000, says marketing rep Jennifer Binney. Before melting any snow with the machine, an operator has to fill it with 1,300 gallons of water and 550 gallons of fuel. “Water is the main ingredient in melting snow,” says Binney. The SND900 uses 9 million BTU (of energy) per hour to heat the water and spray it over the snow. That’s a lot of energy, enough to heat about 75 homes, Binney says.

The melted snow comes out from under the machine “fast and warm,” Binney says. It runs to the nearest storm drain quickly enough that it doesn’t freeze. A filter separates oil and dirt from the water; anything larger than one-eighth of an inch in diameter goes in a “debris basket” that can be emptied and re-attached to the machine while it’s operating.

The SND900 can run continuously for hours at a time and melt about 30 tons of snow per hour—though Binney is quick to caution that there are “no standards” for measuring that, so other snow-melting machine manufacturers may make different claims without a substantial difference in performance.

It’s definitely a drain on a city’s water resources, Binney acknowledges. And it’s a gas-guzzler. But it keeps cities from dumping their dirty snow directly into public waterways.