The last great price bubble is dead

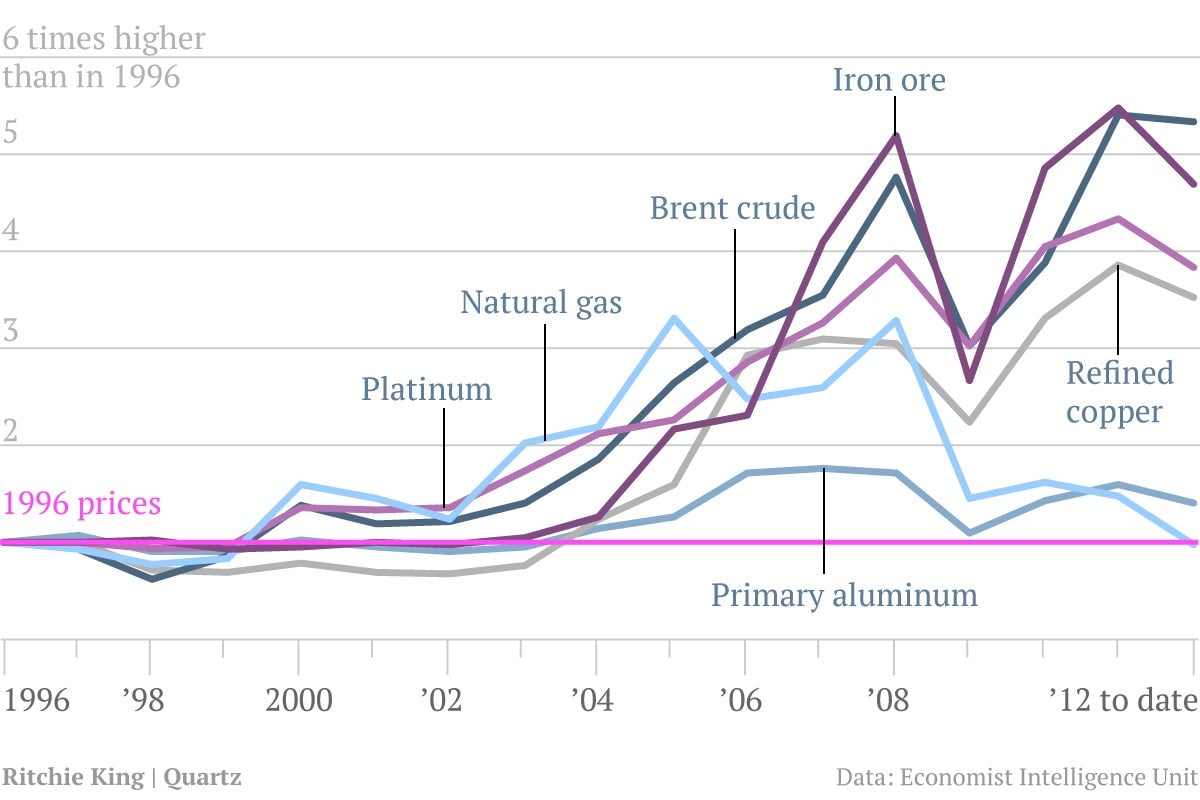

Remember when oil was at $20 a barrel? For the past decade we’ve toiled up the slope of the so-called commodities super-cycle, a rise in metal and hydrocarbon prices steeper than even in the 1970s oil-shock days. It made consumer goods costly but drove torrid profits for traders, miners, investment bankers, and pension funds. But now prices are sinking again, companies are asking to escape debt covenants, countries are facing lower GDP growth, and pension funds are shifting their investments.

Remember when oil was at $20 a barrel? For the past decade we’ve toiled up the slope of the so-called commodities super-cycle, a rise in metal and hydrocarbon prices steeper than even in the 1970s oil-shock days. It made consumer goods costly but drove torrid profits for traders, miners, investment bankers, and pension funds. But now prices are sinking again, companies are asking to escape debt covenants, countries are facing lower GDP growth, and pension funds are shifting their investments.

Some die-hards continue to argue that prices are coming back. US Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke lent this camp some support with his Sept. 13 announcement of a new round of quantitative easing that will push $40 billion a month into the financial system; central bank stimulus tends to drive up commodities prices. In addition, economic historians point out that super-cycles have been known to last more than three decades, meaning that this one theoretically could go on past 2030.

But don’t count on it. Bernanke’s move may buoy oil, copper, and even iron ore for awhile, but China seems much less prepared to stimulate the Asian region with gigantic infrastructure projects. After that, simple economics take over: when the price of a material rises too high, demand for it eventually falls. “A lot of events taking place are conspiring all together to bring [the supercycle] to a close,” says Ruchir Sharma, chief emerging markets analyst for Morgan Stanley and author of Breakout Nations. “The biggest thing is China.”

This equation creates winners and losers. But more on that later because once upon a time, there was demand….

How the super-cycle began

The price surge has always hinged on the demography of China, India and other emerging countries. A wave of urbanization and industrialization there brought massive construction, and supplies of metals and other raw materials were insufficient to meet the unparalleled demand. But in March, Chinese Premier Wen Jiabao reduced the country’s GDP growth target to 7.5%, far below the double-digit rate not uncommon in recent years. The price plunge for basic materials followed—a one-third drop in the price of hard coal used in steelmaking, and a halving of the price of iron ore, to below $90 a tonne.

The boom’s roots actually go back further—to two decades ago and the collapse of the Soviet Union. Vast new commodities supplies opened, often offered at cut-rate black-market prices just as the rise of the BRIC nations got under way, and a decade of profiteering by metals titans and countries like Australia and Russia followed. Such booms, however, also end up attracting atypical investors—everyone seems to want a piece of it.

So it was that, by the mid-2000s, investment banks had persuaded scores of ordinarily conservative individual investors including public employees in developed markets to plow 10% and even 20% of their assets into commodities-based instruments. Between 2006 and 2011, estimates Morgan Stanley’s Sharma, some $400 billion poured into commodity investment funds. One, created by Goldman Sachs, was a basket of commodities that it called the “Goldman Sachs Commodities Index.” The index became the industry standard, filled the coffers of Goldman and other investment banks that used it, and, critics said, exerted undue influence on oil, metals and grain prices. Hence, the bubble.

Now, though, institutional investors are winding down their positions and, in some cases, fleeing. The California State Teachers’ Retirement System is down to just 0.1% of its assets in commodities, while the Illinois Teachers’ Retirement System is completely out.

If you happen to be one of those investors, and believe that China will not return to its hell-bent construction frenzy, at least not any time soon, you likely fall into the post-supercycle crowd. If you conversely believe that China is simply in a down phase and will resume massive stimulus in due course, now may be the time to lay down new bets in commodities. Let’s say the former crowd is correct and that the bubble has burst. Here are some of the losers and winners.

The Losers

Australia: After 21 years of uninterrupted GDP growth, much of it fueled by the coal and iron ore that it sells to China, Australia is experiencing a hangover. It has a massive housing bubble. Meanwhile, the mining companies that drove the rapid growth—BHP Billiton, Rio Tinto and Fortescue Metals Group—have canceled planned big projects, laid off thousands of employees and suggested that worse could come. In the third quarter of the year, mining employment in Australia fell for the first time since the global financial collapse. The country’s jobless rate is at just 5.1%, but the mining slowdown could push it higher.

Fortescue, the world’s fourth-largest iron ore miner, has appeared to be in the worst trouble among the group. Its share price plunged by 14% on Sept. 13 after it asked its bankers for a year’s waiver of payment on $11.3 billion in debt. The company won a reprieve on Sept. 18 with a $4.5 billion credit facility that it says extends its deadline for debt repayment through 2015.

Japan, South Korea, Brazil, Russia: Economists think that Japan’s economy may contract after eking out growth of just 0.2% in the second quarter. South Korea’s own lagging GDP growth, at 2.4% in the first half of the year, has been this slow only twice in the last decade—during the general global plunge of 2009, and before that in 2003. Brazil and Russia are also heavily dependent on commodity exports, and could suffer to an even greater degree.

Big trading houses: Swiss-based commodities trading firms such as Glencore, Trafigura and Vitol have been among the biggest winners in the boom. But now they are having to rethink how to thrive after a long period in which they simply bought and sold. One way is to get directly into the mining business: over the last several months, Glencore has been trying desperately to close a deal to take over the Anglo-Swiss mining company Xstrata.

The Chinese slowdown has only magnified their problems. So too has the internet, which allows for instantaneous transmission of prices, and of news that can affect prices. This reduces the edge that traders used to enjoy by being on the spot in the often far-flung places where commodities are produced.

The Winners

Consumer nations, from the Philippines, to Europe and the US: The greatest beneficiaries of the end of the super-cycle are consumer nations such as the Philippines, Poland, Thailand and Turkey, not to mention the US and Europe. For all, lower raw material costs will mean less spending on expensive imported materials, and a boon for local manufacturing, since costs will be lower. The commodities price plunge is so new that the dividend in terms of absolute savings is not clear. But the raw materials component of many products is substantial. Consider gasoline, chemicals and other fuels, up to 80% of which are comprised of crude oil. When oil prices drop, as they have been, billions of dollars in economic cost are shaved off too. “This has been a big drag” on such economies, said Sharma. “They have paid the price of the super-cycle.“

Now read on about how cheap energy could change the geopolitical power balance.