A hedge funder is using an obscure new law to mess with drug companies

This post has been corrected.

This post has been corrected.

Kyle Bass, the hedge fund manager and founder of Hayman Capital Management who made his reputation by betting correctly on the housing market in 2008, is using an obscure legal process to try to invalidate the patents that make ever increasing (paywall) drug prices possible.

He portrayed his new strategy (paywall) as an effort to combat excessive medical costs in a presentation in Copenhagen in January. Of course, he also stands to make a good deal of money shorting his targeted drug companies. (Quartz has reached out to Bass for comment, and will update this post with any response.)

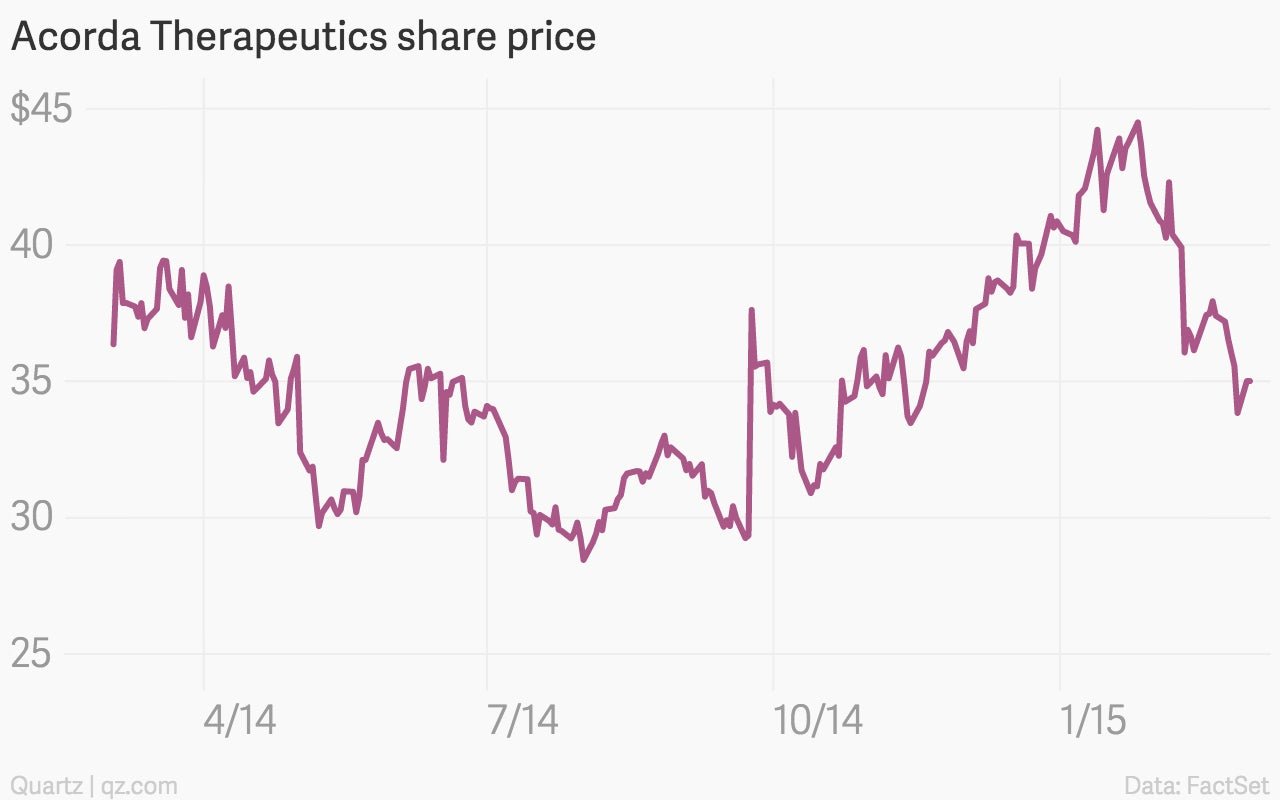

Bass’s first foray was Feb. 10, when he filed a petition to challenge the basis for one of the drugmaker Acorda’s patents on the multiple sclerosis drug Ampyra, using an obscure new process called an “inter partes review.” His move immediately sent the stock down nearly 10%:

The inter partes review (IPR) is an administrative patent review process that goes through the United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) rather than a court. It was instituted in the fall of 2012, and it differs from the previous regime (inter partes reexamination) in a way that makes it highly appealing to someone like Bass.

The administrative approach is vastly cheaper than a court appeal, which requires a patent infringement and a lawsuit, making it tough for a hedge funder like Bass to do, because he’d have to find a drug company partner to take the risk of an actual patent infringement. IPR requires no infringement for a patent challenge to proceed.

There’s also a lower standard of proof with IPR. District court requires a very narrow interpretation of patent claims, but the United States Patent and Trademark Office requires the broadest possible interpretation. And the process has a time limit of a year, whereas court challenges can take much longer.

IPR tends to favor the party challenging the patent, and is much more effective at getting patents invalidated than reexamination: Challenged claims are overturned at about twice the rate as they were under the previous regime, and it happens twice as quickly, according to an analysis of the early evidence published in the University of Chicago law review.

Bass’s move to use IPR is a new and unusual form of activism. It’s closer to the hedge fund manager Bill Ackman’s crusade against Herbalife than a more traditional proxy fight. The goal isn’t a Securities and Exchange Commission investigation though, but rather to undermine the actual products that make these companies money.

Real success for Bass, beyond any initial drop in the stock price upon announcing a challenge, is actually getting a patent invalidated and opening a firm up to generic competition sooner than the market expected.

Many drug companies are heavily reliant on one or a few drugs. Acorda, for example, gets a substantial majority of its revenue from Ampyra, which improves walking in MS patients.

Primary patents are going to be tough to overcome, but many companies resort to less sturdy patents in an attempt to extend their exclusivity, patenting different formulations, methods of administration, or combinations with other drugs.

Some of those patents may be vulnerable. And Bass doesn’t necessarily need to immediately open a company up to competition; just knocking several years off the length of the patent will have a market effect.

This is by no means a sure thing. IPR can only be used for claims of obviousness, a measure of uniqueness and differentiation from prior art, which is limiting.

Generic drug companies that can actually manufacture these medicines might be in a better position to challenge patents than hedge funds, because they have more experience, plenty of money, and a lot of incentive. They’re also likely better versed at which patents are most vulnerable to off-brand competition.

But for drug companies, there are some downsides to the IPR process. Should a firm successfully overturn a patent in court, it gets a six-month exclusive right to manufacture the drug, which gives them some pretty powerful motivation to do it in the courts.

Eight other drug companies are challenging Acorda’s patents in court, Robert Cyran reported at the New York Times (paywall). The company also has patents on Ampyra other than the one that Bass is challenging.

As for Bass’s claim that this is a quest to reduce drug pricing: Sure, creating more generic competition would help reduce prices, but there are some limits. The most expensive drugs are unlikely to be affected because they tend to be biologics, drugs that use the processes of the body to fight diseases and are made in animal cells or bacteria which are hard to replicate even after they go off patent. Or they are relatively new drug innovations that aren’t vulnerable to a claim of obviousness.

Unless Bass is able to file IPR petitions at a very substantial volume and with a dramatic success rate, it will only be a drop in the drug-pricing bucket.

Correction (March 3, 2015): An earlier version of this post mischaracterized the six-month exclusivity that drug companies win when they overturn a patent in court.