Apple’s not-so-secret weapon in streaming music

Electric cars and smart watches may be getting all the attention right now, but don’t forget there’s another ancillary business Apple is involved in—one that it has already revolutionized once, and stands a good chance of revolutionizing again. It’s called music.

Electric cars and smart watches may be getting all the attention right now, but don’t forget there’s another ancillary business Apple is involved in—one that it has already revolutionized once, and stands a good chance of revolutionizing again. It’s called music.

Music is important to Apple. It was the iPod that kicked off the company’s renaissance under Steve Jobs, setting the stage for its incredible, decade-and-a-half rise, which recently pushed its market value above a record $700 billion.

The company’s current CEO, Tim Cook, has also staked some of his credibility on music: After all, the biggest acquisition in the company’s history, its $3 billion purchase of Beats, a headphones and streaming music operator co-founded by the rapper Dr. Dre, happened on his watch.

Now Apple is gearing up for its next big push in music, with a long-awaited foray into streaming subscriptions, and all signs indicate that the company is taking this venture very, very seriously.

Multiple reports suggest Apple will soon incorporate the Beats streaming platform into its next update of iOS, its mobile operating system, perhaps under the brand of its media player and content library app, iTunes. Through the iTunes store, Apple already has a staggering 800 million credit cards of customers on file. If it could convert just a tiny fraction of those into streaming subscribers, it would become easily the biggest player in the industry (a crown worn now by Spotify, which said last month it has 15 million subscribers).

Billboard Magazine released a report last week arguing that Apple doesn’t want to just compete in music, it wants to own the record business. The piece shed some light on how it might go about this:

The price being debated: $7.99 per month, down from Beats’ now-standard—and arguably too high—$9.99 a month, with no “freemium” model. (The sweet spot for consumers, at which profit is maximized for the labels: $3.99 to $4.99, say experts.)

Spotify, and similar services like Rdio, typically cost $10 a month in the US for their paid services. So it looks like Apple is going to undercut everyone else in on-demand streaming from the get-go. It could be a boon for consumers, since Spotify is under pressure to eliminate its free, ad-supported tier of service. For rival streaming providers and the creative community, less so.

Talk that Apple has been considering prices as low as $5 a month did not go unnoticed in streaming industry circles: “There is an exorbitant amount of chatter in the industry that they [Apple] are going to compete on price,” Rhapsody CFO Ethan Rudin recently told Quartz. “All indications I have received is that is what it is: chatter. There is a renewed point of view that perhaps they could be giving away too much value.”

It is difficult to make money selling streaming music subscriptions. Despite artists’ complaints about how little they are paid, licensing costs for streaming companies are burdensome. To get access to the music they need to operate, streaming services typically must pay upfront fees and even give up equity to record labels. What’s more, royalties are typically fixed at a certain percentage of a company’s revenue—Spotify, for example, has stated publicly that it pays out 70% of its revenue to rights-holders in royalties.

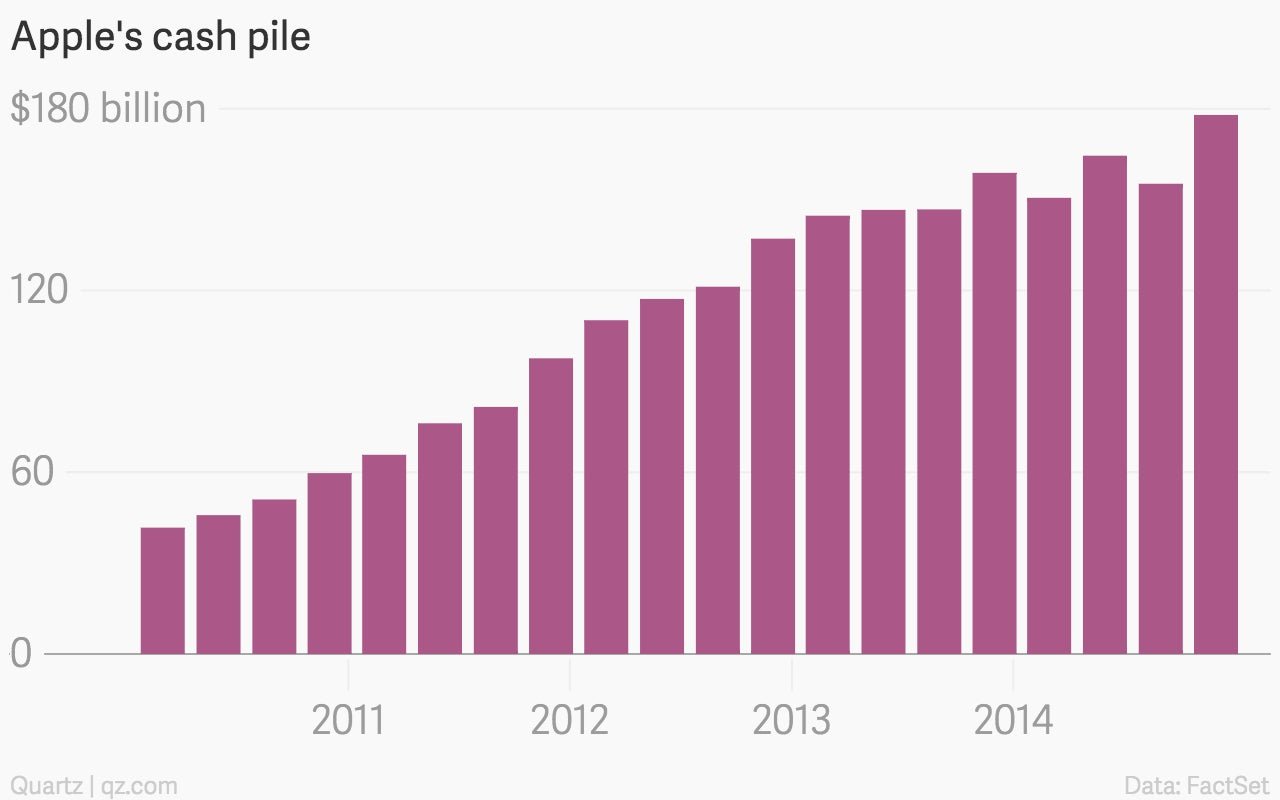

Apple might be able to get a better deal from record labels than others because it’s so huge. But at the end of the day, the real reason Apple can offer a cheaper service than Spotify and others is because it simply doesn’t need to make any money from streaming. It’s just a way to keep users locked into the iOS ecosystem so it can sell more devices. The company made a staggering $18 billion in profit last quarter alone. It has mountains of cash ($179 billion at the end of 2014, to be precise) sitting idle on its balance sheet.

It can afford to break even or lose money in music. And if other services try to respond by cutting their own prices, has the financial firepower to outlast them in any price war.

Apple could also flex its financial muscle to sign exclusive deals with artists for music that wouldn’t be available on other platforms. The company has denied wild rumors that it could acquire Taylor Swift’s record label (which would have been a major PR coup since she withdrew her back catalog from Spotify). But the idea of getting exclusive content for the new service makes sense, and is not unfamiliar to Apple (remember “iTunes Originals“?).

Apple’s gargantuan cash pile also means, in theory, that it can afford to pay the kind of royalty rates songwriters and performers think they deserve. But there is some skepticism in the creative community about whether that will actually happen. This is business, after all. ”I’d be careful about expecting them to be a knight in shining armor for digital music,” says Casey Rae, an adjunct professor at Georgetown University and the CEO of the Future of Music Coalition, an advocacy group for independent musicians. “What might end up happening is they [Apple] could control many more—if not all—the chips in how music is licensed.” Having one company dominating the music industry could be a scary prospect. Apple is generally on good terms with most artists (Jon Bon Jovi aside), but this could change if its dominance grows.

To be clear, Apple hasn’t always got it right in music. iTunes Radio, a passive webcasting service that was meant to kill Pandora in the US, has underwhelmed. The company’s recent (forced) giveaway of U2’s latest album to all of its device owners was an embarrassing debacle. For now, at least, it seems to be taking a more considered approach with streaming.

The company has a reputation for waiting for others to move first, and then ruthlessly seizing a market. It will be fascinating to see how it uses the tactic, and its imperious financial position, in music again.