How the US government rigs the deck for wealth inequality

The latest data from the Federal Reserve confirms that US wealth inequality has been growing for decades—and it’s not accidental.

The latest data from the Federal Reserve confirms that US wealth inequality has been growing for decades—and it’s not accidental.

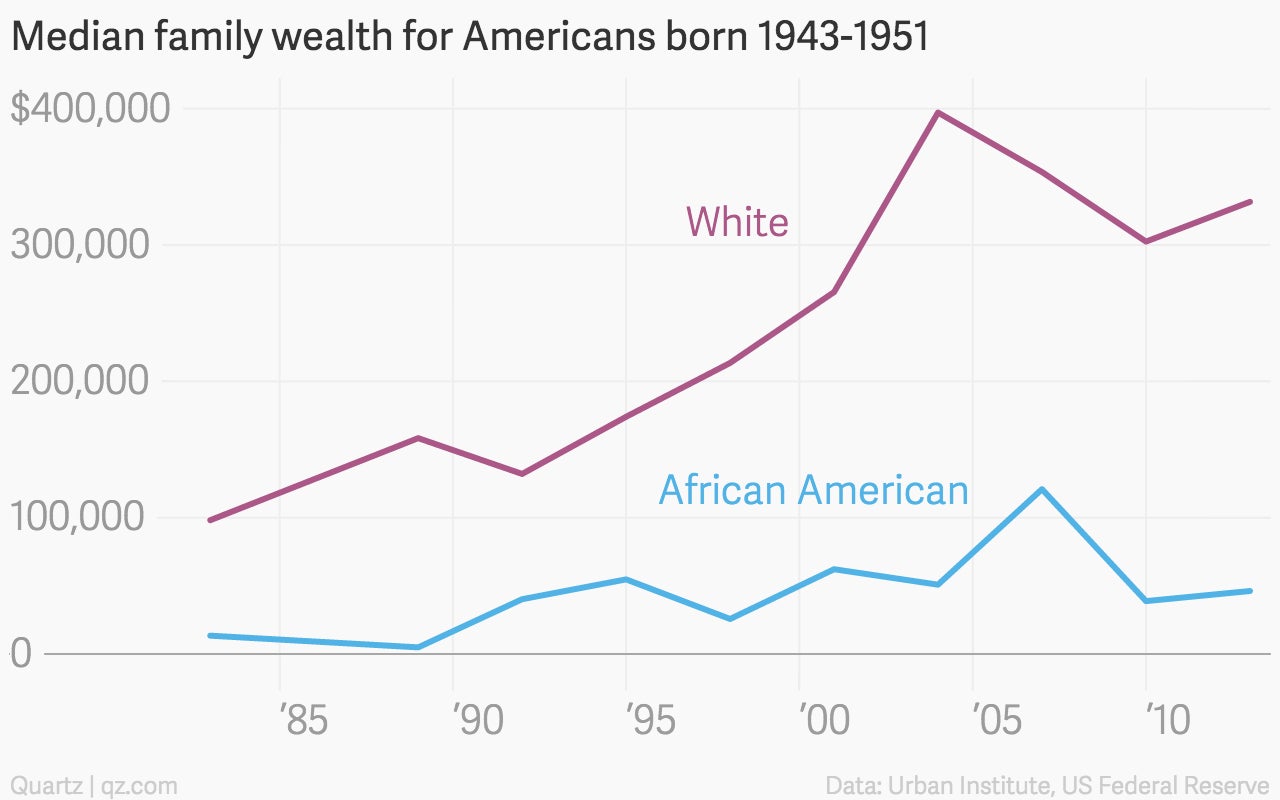

The Urban Institute, a center-left public policy research center, assembled nine interesting charts from the Fed’s latest survey of consumer finances. While you may be familiar with discussions of income and wealth inequality, one chart that stuck out was a look at family wealth accumulated by members of the Baby Boom generation, over time and by race:

That’s a pretty significant disparity, and it’s not necessarily an accidental one. People in the US build their wealth largely through two main assets: Their home and their retirement savings. Recent research shows that African and Hispanic Americans are less likely to take full advantage of tax-deferred 401k retirement plans. But we can see that on the aggregate, US policy attempts to urge savings and investment are typically geared toward the wealthy, missing the opportunity to impact the people most in need of assistance when it comes to building assets.

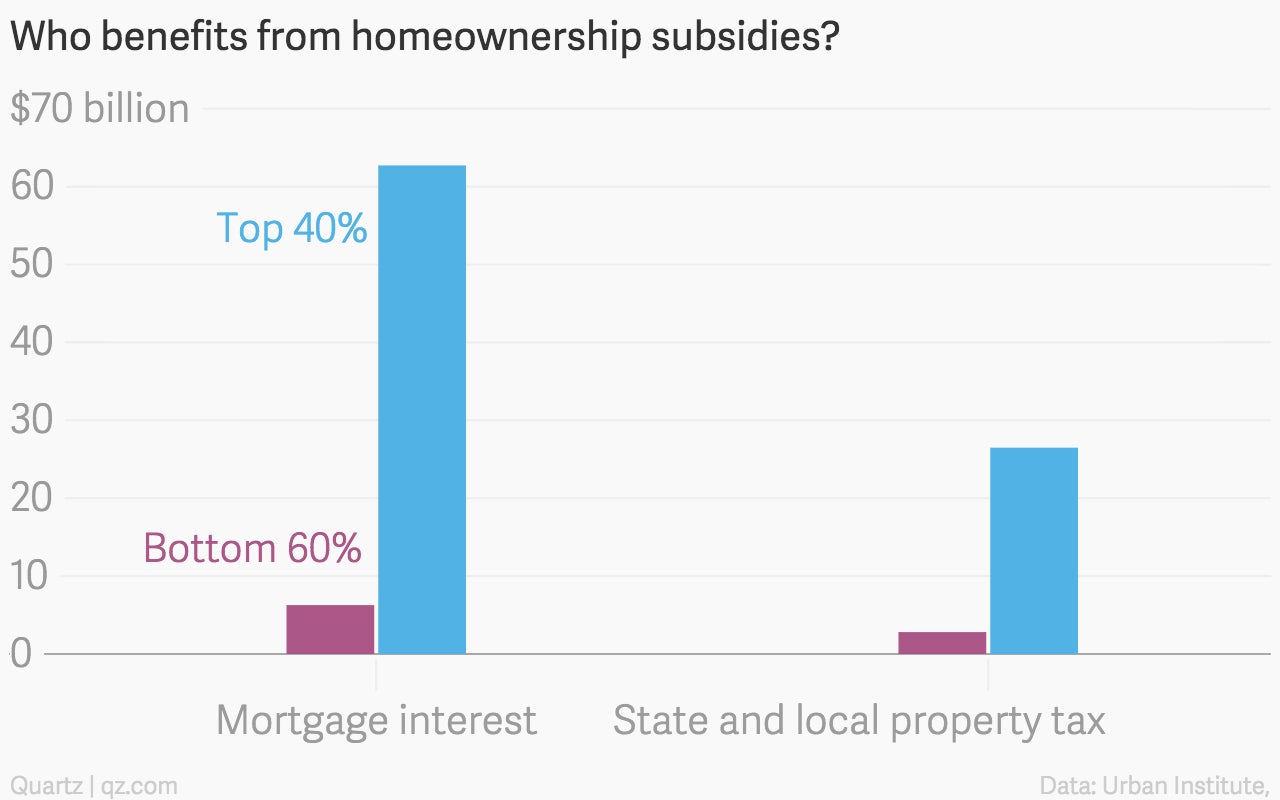

Consider two tax subsidies largely directed home-owners: the mortgage-interest deduction, and the state and local property-tax deduction. While they saved Americans $98 billion in 2013, almost all of that money went to the top 40% of income earners:

Then there are tax subsidies designed to incentivize savings for retirement. The US gave tax breaks worth $91 billion a year to those using employer-sponsored retirement plans like the 401k, $5.2 billion to Americans using Individual Retirement Accounts, and $1.2 billion to Americans taking advantage of the Saver’s credit, which is specifically targeted at low-income workers. Once again, the top 40% of Americans see the most significant benefits.

A big part of this problem is delivering social policy through the tax code: Because people who earn the most also pay the most taxes, they will always benefit disproportionately from benefits implemented as tax breaks. But since many of these breaks are ostensibly to generate mobility by allowing people to earn their way to wealth, they are missing the mark—and there are knock-on effects as well, like breaks for homeowners contributing to the over-investment in housing that led to the 2008 crisis.

These findings won’t surprise many advocates of smarter asset-building policy: Simple fixes, like automatically enrolling workers in savings plans or phasing out the mortgage-interest tax deduction in favor of a first-time home buyer’s tax credit, could help broaden the effects of these policies, and new policies, like a universal children saving’s accounts, could do even more to build prosperity in the long-term.