Your workplace is probably killing you

We may be long past the days of Upton Sinclair’s The Jungle—the seminal book that depicted the harsh working conditions in America’s meatpacking industry in the early 20th century—but the workplace is still hazardous to our health.

We may be long past the days of Upton Sinclair’s The Jungle—the seminal book that depicted the harsh working conditions in America’s meatpacking industry in the early 20th century—but the workplace is still hazardous to our health.

Workplace stress—such as long hours, job insecurity, and lack of work-life balance—contributes to at least 120,000 deaths each year and accounts for up to $190 billion in health care costs, according to new research by two Stanford professors and a former Stanford doctoral student now at Harvard Business School.

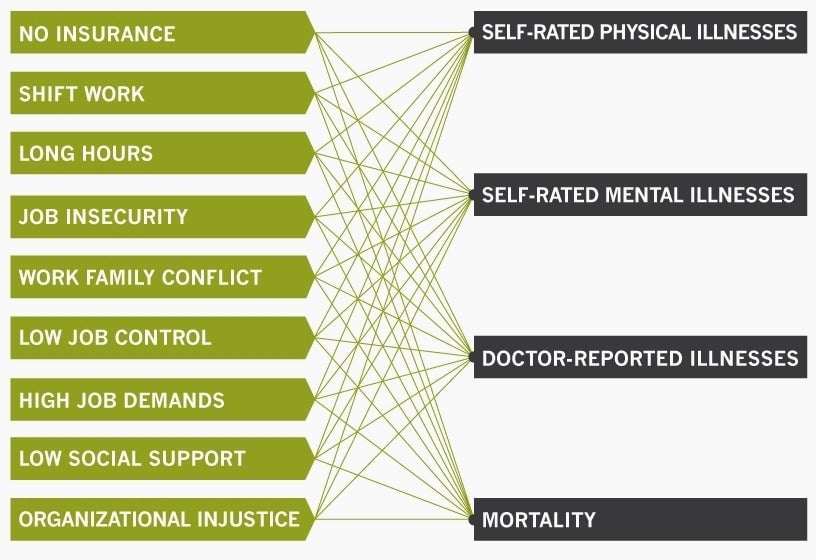

“If employers are serious about managing the health of their workforce and controlling their health care costs, they ought to be worried about the environments their workers are in,” says Jeffrey Pfeffer, a Stanford professor of organizational behavior. Pfeffer, with colleagues Stefanos A. Zenios of Stanford GSB and Joel Goh of Harvard Business School, conducted a meta-analysis of 228 studies, examining how 10 common workplace stressors affect a person’s health.

They found that overall, these stressors increase the nation’s health care costs by 5% to 8%. Job insecurity increased the odds of reporting poor health by 50%, while long work hours increased mortality by almost 20%. Additionally, highly demanding jobs raised the odds of a physician-diagnosed illness by 35%.

“The deaths are comparable to the fourth- and fifth-largest causes of death in the country—heart disease and accidents,” says Zenios, a professor of operations, information, and technology. “It’s more than deaths from diabetes, Alzheimer’s, or influenza.”

Physical and psychological impact

The stressor with the biggest impact overall is lack of health insurance. It ranks high in both increasing mortality and health care costs. Another big driver of early death is economic insecurity, captured in part by unemployment, layoffs, and low job control.

The ramifications for the uninsured should come as no surprise, Pfeffer says, but what did surprise the team was the high impact of psychological stressors. Work-family conflict and work injustice had just as much impact on health as long work hours or shift work.

For example, employees who reported that their work demands prevented them from meeting their family obligations or vice versa were 90% more likely to self-report poor physical health, the researchers note. And employees who perceive their workplaces as being unfair are about 50% more likely to develop a physician-diagnosed condition.

How to fix wellness programs

Pfeffer first became interested in this subject while working on the Stanford Committee for Faculty and Staff Human Resources. Many companies and organizations such as Stanford, he says, institute wellness programs that focus on encouraging employees to eat better or exercise more. Meanwhile, these companies overlook the atmosphere of workplace setting itself.

Smoking cessation programs or incentives to lose weight focus on individual behavior and ignore management practices that create stress and set the context for employee choices. “Lots of research shows that your tendency to overeat, overdrink, and take drugs are affected by your workplace,” Pfeffer says. “When people like their lives, and that includes work life, they will do a better job of taking care of themselves. When they don’t like their lives, they don’t.”

Focus policy on prevention

Good health matters to people and employers, but it also matters to government. The US spends a higher proportion of its GDP on health care than most other industrialized countries, and significantly more per capita, the researchers note.

The researchers suggest regulations and policy changes that go beyond current overtime restrictions and wage laws, and focus on prevention. “Forty or 50 years ago, I could put toxins into the air or water, and someone else had to pay to clean it up,” Pfeffer says. “We decided that wasn’t very good because it costs more to remediate than prevent. It’s true in the case of human health as well,’’ he says. “It costs more to remediate the effects of toxic workplaces than it does to prevent their ill effects in the first place.”

One suggestion is tax incentives that could encourage employers to offer more work-family balance or reduce layoffs. Non-regulatory actions like guidelines or best practices might also prove fruitful.

The study has some limitations, the researchers acknowledge. They are unable to make strong causal inference linking these stressors to poor health because the studies they used are observational. “It is association—it doesn’t mean that there’s causation,” Zenios says. “There may be other factors going on.” Also, people handle stress differently, so it’s difficult to assess how attitudes toward stress affect the results. Finally, the researchers looked at only 10 stressors, examining simple ones that could be addressed by management changes.

Rethinking the workplace

Improving the work environment is not a Herculean feat, and many companies are already thinking beyond programs such as smoking cessation to those that address these stressors, Pfeffer says. Companies need to get serious about creating a workplace where people feel valued, trusted, and respected, where they are engaged in their work, don’t worry about losing their jobs, and where they can get home in time for family dinner, he says.

“My meta point is that we have lost focus on human well-being. It’s all about costs now. Can we afford this, can we afford that? Does it lead to better or worse financial performance for the company?” Pfeffer says. “We’re talking about human beings and the quality of their lives. To me, that ought to get some attention.”

Jeffrey Pfeffer is the Thomas D. Dee II Professor of Organizational Behavior. Stefanos A. Zenios is the Charles A. Holloway Professor of Operations, Information, and Technology and Professor of Health Care Management.

This post originally appeared at Stanford Business.