“There’s no such thing as an accidental repost:” likes and retweets Russia has used to prosecute activists

Over the past few years, more than 20 people in Russia have been officially convicted or punished for their actions on social networks. Individuals have been fired for selfies, fined for retweets, had their homes searched because of “likes,” and arrested and later released on bail with travel restrictions for a retweet. These are the most notorious stories in Russia about people persecuted for their actions online.

Over the past few years, more than 20 people in Russia have been officially convicted or punished for their actions on social networks. Individuals have been fired for selfies, fined for retweets, had their homes searched because of “likes,” and arrested and later released on bail with travel restrictions for a retweet. These are the most notorious stories in Russia about people persecuted for their actions online.

Likes

Kazan, Republic of Tatarstan:

“Because of my occupation, I’ve had to reckon with Tatarstan’s criminal justice system more than once. At the time [in 2012], we’d just carried out a few dozen large demonstrations throughout the region, each time drawing more people,” Filippov remembers today. “An organization like ours, with an oppositionist core, profoundly worried Tatarstan’s ethnocratic local elite, in particular the republic’s president.”

The only thing that surprised Filippov was what came next, at his questioning the following morning.

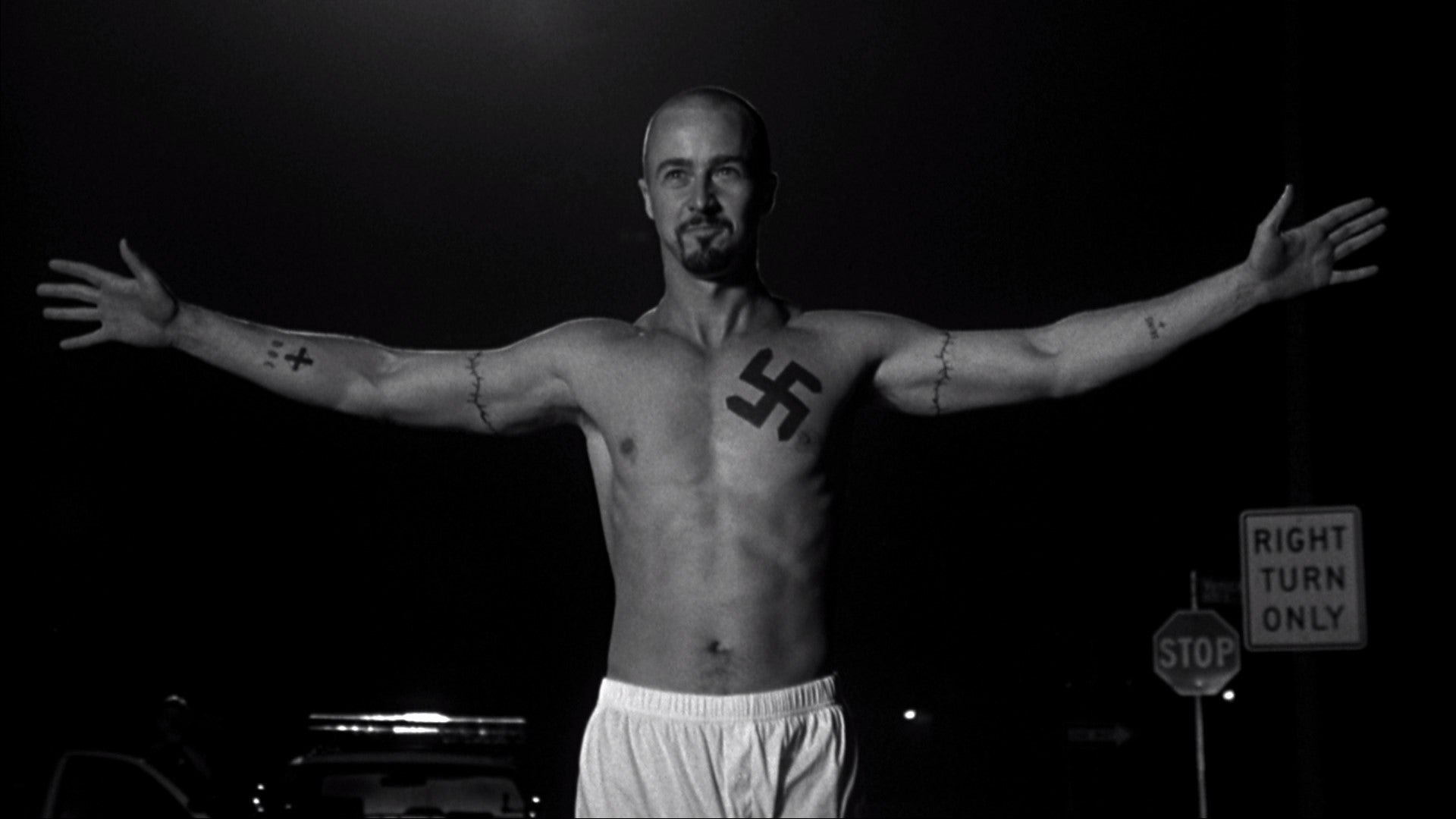

The officers interrogating Filippov showed him several screenshots from his VKontakte social media page taken in 2011, explaining that “an investigation was underway to determine if the images constituted the dissemination of extremist materials, materials inciting ethnic hatred, or materials promoting fascism or Nazism.” All charges were based on images from a scene in the well-known film American History X, where the actor Edward Norton stands smiling with his arms outstretched, his head shaved, and a swastika tattooed to his chest.

“I understood perfectly the absurdity and legal ridiculousness of the charges,” Filippov says. The movie, of course, is actually an acclaimed anti-fascist film; it’s not banned in Russia; it’s been aired on television; and Edward Norton was even nominated for an Oscar for his performance. Not only that, but Filippov never even posted the photo—he’d only clicked that he “liked” the image. (In 2011, VKontakte automatically populated photo albums on users’ walls with content they’d “liked” elsewhere on the site.) Filippov summoned a computer programmer to his trial to explain these technicalities to the court, but the judge refused to listen.

At first, prosecutors planned to charge Filippov with extremism, a criminal offense in Russia, but two months later they reduced it to “promoting Nazi symbols,” which is only a civil offense. “For criminal offenses, it’s necessary to establish the crime and the criminal’s motive; they found the former, but proving any motive turned out to be a problem, so they fell back on accusing me of [Nazi] propaganda,” Filippov explains.

From the prosecutors’ standpoint, this propaganda consisted of a single act: clicking the ‘like’ button. In doing so, I wished negative consequences on Russian society and cultivated hostility and hatred. Prosecutors insisted that I wouldn’t have “liked” the photo, if I hadn’t wished to incite these very things.

The trial concluded in August 2012. Filippov was fined 1,000 rubles (about $30 at the time). Today, Filippov is no longer a member of the Russian All-People’s Union, though he continues to be active in politics. Tatarstan’s local police and attorney general, he says, remind the public at every opportunity of his supposed past involvement in Nazi propaganda.

When the court announced its verdict, news headlines read “A Russian Citizen Has Been Convicted of a ‘Like’ for the First Time in History.”

Reposts

Moscow:

Navalny’s anti-corruption organization received a document from a local Internet provider, titled “Warnings Against Violating the Law,” signed by Moscow’s deputy district attorney, admonishing Navalny’s staff for systematically publishing texts, photos, videos, and audio in his name, encouraging his readers to participate in unsanctioned mass demonstrations, despite the ban on Navalny using the Internet.

The district attorney warned ISPs that providing services for the transfer and dissemination of such information facilitates the “violation of a court injunction,” as well as “violations of the law.” The state’s position was clear: it considered any promotion of Navalny’s blog to be illegal. The document was also sent to Afisha-Rambler-SUP, which owns LiveJournal, one of the most popular blogging platforms in Russia.

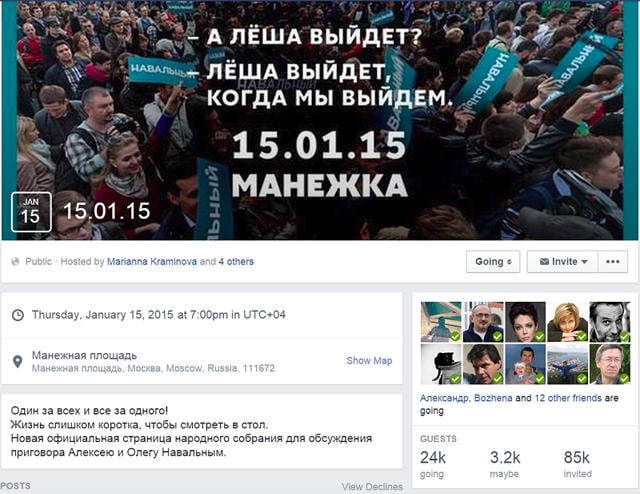

Last Dec., Facebook complied with an order from the Attorney General to block Russian users’ access to an event page created by organizers of an unsanctioned rally outside the Kremlin in Moscow, scheduled for Jan. 15, 2015, in support of the Navalny brothers, whose criminal sentences were expected to be announced on that day. All reposts of this event disappeared from users’ walls, following Facebook’s action. The Navalny event became so contentious that Roskomnadzor even ordered a Ukrainian news website to delete a story about the protest.

Barnaul, Altai Krai:

Teslenko was taken in for questioning and told he was a suspect in a criminal investigation into “inciting hatred,” facing up to five years in prison—all for an online post, which he copied and reposted to his own VKontakte page.

Teslenko, a liberal activist and a former candidate for city council, was no stranger to the police. In the fall of 2013, he’d already been fined a thousand rubles for “mass dissemination of extremist materials” for reposting on VKontakte a video by Alexey Navalny, titled “Remind the Crooks and Thieves About Their 2002 Platform!” The message was directed at United Russia, the country’s ruling political party.

This time, however, Teslenko feared he wouldn’t escape with a simple fine. “They told me that my case was being handled by a full-fledged investigator from the Federal Security Service [FSB], and I decided they weren’t joking around anymore,” Teslenko recalls today.

The day after police searched his home, Teslenko grabbed his wife and 18-month-old daughter and loaded everyone onto a bus headed for Novosibirsk. (One doesn’t need to show any identification to travel by bus between cities in Russia.) They went to a friend’s house, where Teslenko promptly got a haircut and shaved his beard, to make it harder to recognize him. Then he began to think of what to do next.

Police later filed a criminal case against Teslenko for a “Russophobic post” on his VKontakte page. The post, signed by Anonymous, said “roosha is sh*t-people, a vermin-people, and a cancer” that hates the whole world and believes fascists control Ukraine. The authors of the post said they wished nothing good on the people of such a nation. One of Teslenko’s VKontakte friends, a university student in Altai and a member of the same political party, asked him to delete the post, saying it offended him. When Teslenko refused, the friend wrote a formal complaint to the Attorney General.

The SOVA Center for Information and Analysis, a Russian nonprofit organization, says Teslenko’s “Russophobic” post has a “clearly anti-Russian bent (in an ethnic sense),” but comes with several mitigating factors: first, it had a small audience; second, it was only a “re-publication”; and third, the legality of the charges are dubious, insofar as “it remains unclear if calls to discrimination should be prosecuted when they’re made in Russia but addressed to the authorities of a foreign country, and when Russian citizens aren’t being targeted.”

Before police ever issued an arrest warrant for Teslenko, he and his family flew to Kiev, where they managed to find accommodations at a homeless shelter. Afterwards, they went as far west in Ukraine as possible, to the city of Uzhhorod. In Nov. 2014, they were granted refugee status. Now they’re waiting for passports that can take them further west, beyond Ukraine, living in Mezhyhirya, at former President Yanukovych’s old residence, part of which now functions as public housing. Teslenko says they can’t find work in Kiev and are planning to move to the United States, after winning a green-card lottery.

Chelyabinsk, Chelyabinsk Oblast:

In Mar. 2014, Zharinov clicked the “share with friends” VKontakte button under a public appeal released by Pravyi Sektor (Right Sector), a Ukrainian organization banned in Russia for extremism. The group’s message said Russia’s fate would be decided in Ukraine, told Russians they, too, can fight against “Putin’s Chekist regime,” and called for mass demonstrations and the creation of guerrilla bands to shut down highways and dismantle Russia’s military infrastructure. Zharinov says his interest in Pravyi Sektor is purely academic, and denies any sinister aims in reposting the message, though he considers it a “poor decision” in hindsight.

The day after reposting Pravyi Sektor, Zharinov joined an anti-war picket, carrying a sign reading “No to war.” On Mar. 4, two police officers from a special anti-extremism unit escorted him to the district attorney’s office, where he was issued an official warning. Two months later, agents from the FSB called him in for questioning. Two months after that, police said Zharinov had “publicly advocated extremist activity,” charging him with violating Article 280 of Russia’s criminal code, which carries a maximum prison sentence of four years.

Someone named Petrov, a man Zharinov has never met, triggered the FSB’s investigation when he filed a complaint with the police. Mr. Petrov saw in Zharinov’s actions a “crime against the constitutional order and security of the state.” Zharinov’s indictment says he “willfully and intentionally” sought out online materials of “an oppositionist nature,” which he then posted on his VKontakte page.

According to the investigation’s conclusions, Pravyi Sektor’s public appeal paints as its enemy “the Russian state generally and Vladimir Putin specifically, likening their images to Adolf Hitler and fascist Germany.” FSB agents, it turns out, tapped Zharinov’s telephone, and his case includes a whole stack of psycho-linguistic reports based on what the agents overheard. The Chelyabinsk Justice Ministry’s chief specialist testified that “there’s no such thing as an accidental repost, insofar as posting any materials requires clicking through a series of options.”

A detective from the anti-extremism police unit filed a report noting that his office had “tracked” Zharinov’s participation in several opposition rallies since 2012, and a few pickets in support of Alexey Navalny. (The report misspells the word “opposition.”) One of the state’s key witnesses is a 21-year-old student named Anton Miroshnikov, who complained to the FSB about Zharinov’s VKontakte repost after he saw a news report about it, saying it offended him. In his testimony, Miroshnikov, “as a patriot of his country,” thanks “the authorities” for “suppressing such acts.” Ever vigilant, he also asks police to investigate a second Internet user for “signs of extremism,” providing a link to the suspect’s VKontakte page.

Konstantin Zharinov isn’t the only person to face criminal charges for reposting Pravyi Sektor materials; the honor also belongs to 19-year-old Ivanovo resident Liza Lisitsina, whom FSB agents arrested in the middle of a university lecture on ontology and epistemology. Lisitsina’s case has yet to go to trial.

Retweets

Kemerovo, Kemerovo Oblast:

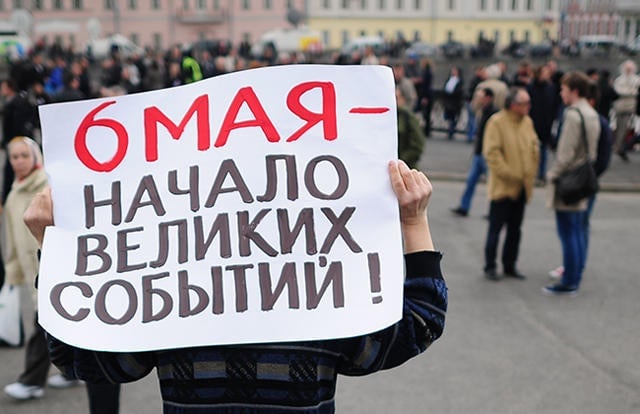

Kalinichenko now stands accused of violating Criminal Code 280 (“calling publicly for extremist acts”) because he retweeted a photograph. The picture, taken on May 6, 2013, at Patriarch Ponds in Moscow, is of a leaflet reading “Enough demonstrating—it’s time to act!” signed by a group calling itself the First Resistance Detachment. The human rights organization Memorial has urged authorities to drop its case against Kalinichenko immediately, saying the charges are “politically motivated.”

Though the leaflet’s text, which calls for the destruction of corrupt officials’ property, formally violates Criminal Code 280, Memorial maintains that prosecuting Kalinichenko is illegal:

Stanislav isn’t the author of the leaflet, he isn’t the author of the photograph, and the charges against him are based solely on the fact that he retweeted the message contained in the photograph. He didn’t advocate any acts; he merely once disseminated a piece of information. As the leaflet was not officially recognized as extremist, in our view, there are no grounds for charging Kalinichenko with even a civil offense.

Memorial also says Kalinichenko is being prosecuted selectively, given that none of the hundreds of others who retweeted the photograph have faced any charges:

The case is political insofar as it is an assault on the freedom to disseminate information that’s clearly associated with the opposition. This case fits a general ‘crackdown’ trend in Russia of restrictions on the freedom of speech online. Specifically in Kemerovo, there is constant pressure on the free press and on bloggers who criticize the local government.

Kalinichenko is currently out on bail, not allowed to leave Kemerovo, and he’s trying to sue the police officers who arrested him. Throughout his legal battle, among other things, he’s gone 42 million rubles ($630,000) into debt. His trial opened on Nov. 5, 2014, and it has yet to produce a verdict. On LiveJournal, it’s possible to follow the events of his trial almost in real time, thanks to sympathetic live-bloggers.

Follow Egor on Twitter at @davay_llama. This post originally appeared at Meduza.