The sun is setting on Britain’s banking empires

It would be difficult to call 2014 anything more generous than an annus horribilis for many of Britain’s largest, oldest, financial institutions. This week, many of those storied banks tallied up the damage, took drastic punitive measures, and forecast more upheaval.

It would be difficult to call 2014 anything more generous than an annus horribilis for many of Britain’s largest, oldest, financial institutions. This week, many of those storied banks tallied up the damage, took drastic punitive measures, and forecast more upheaval.

These banks remain sprawling global giants, but perhaps not for much longer. Most are now in full retreat, unravelling empires built up over decades—centuries, even.

RBS counts the cost

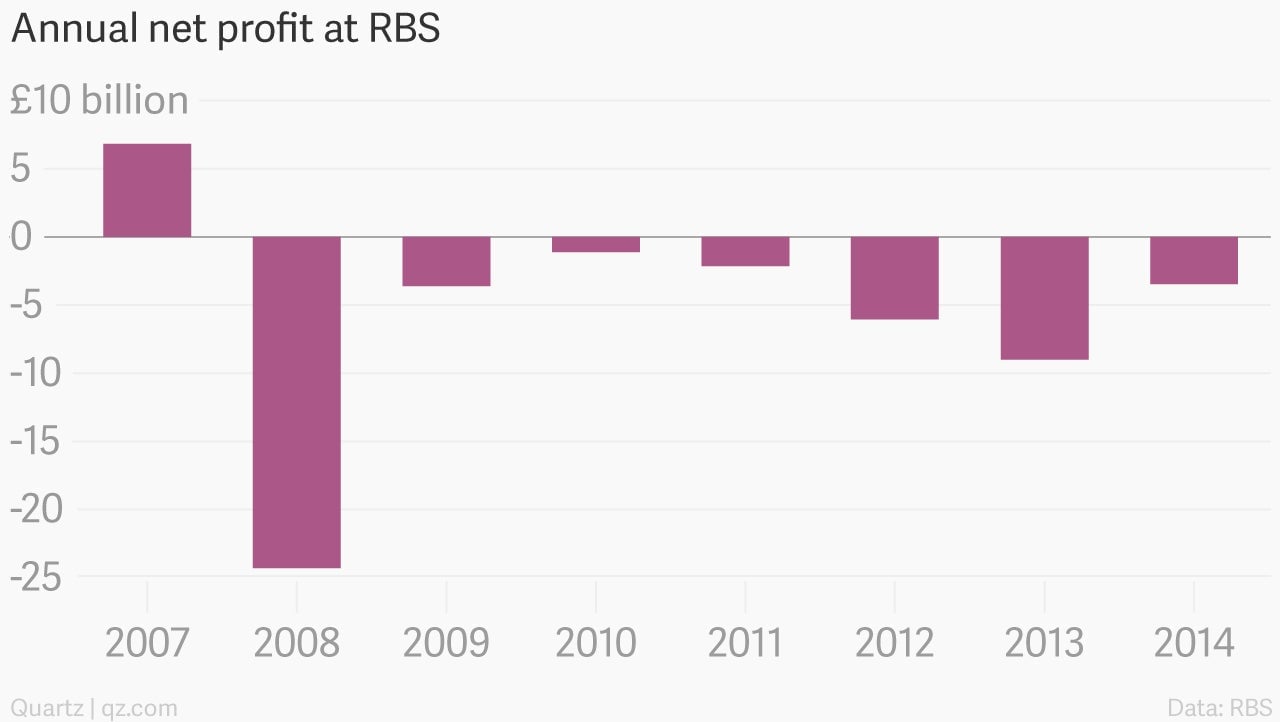

RBS, founded in 1727, reported its seventh consecutive annual loss today. The £3.5 billion ($5.4 billion) loss in 2014 brings the bank’s cumulative losses since 2008 to a whopping £50 billion:

RBS is still majority owned by the British government, following a £46 billion bailout during the depths of the global financial crisis. Its shares remain below the break-even point for taxpayers, and management warned today that things could get worse before they get better.

The bank, like so many others, is mired in scandal and legal trouble—penalties and settlements amounted to more than £2 billion last year and will be “substantial” again this year. RBS CEO Ross McEwan also said that job cuts would be “substantial” as a result of a radical restructuring of the group’s misfiring investment bank.

The group will quit eastern Europe, the Middle East, and Africa, and “substantially” reduce—there’s that word again—its operations in Asia and the US. Once present in more than 50 countries, RBS’s investment bank will only operate in 13 by 2019, mainly in western Europe. The bank also announced the sale of a large North American loan portfolio today.

The bank is “no longer chasing global market share,” according to McEwan, aiming instead to build a “stronger, simpler, and fairer bank” that focuses on the UK and Ireland above all. Chairman Philip Hampton will leave RBS in August.

Standard Chartered cleans house

That is a rather minor management reshuffle compared with the total clearout at Standard Chartered. The London-based, Asia-focused bank, which traces its roots to a Queen Victoria-chartered bank that started in India and Shanghai in the 1850s, said today its chief executive, chairman, Asia CEO, and three independent non-executive directors will step down.

Peter Sands will leave the bank after eight years as CEO, the last few marked by damaging settlements for breaking US regulations against money laundering. From June, the bank will be run by American-turned-British citizen Bill Winters, the former head of investment banking at JP Morgan Chase, who is famous for pinning the 2008 financial crisis on “greedy bankers, investors, and borrowers.”

The move follows StanChart’s decision to close its global equities business, and cut 4,000 retail banking jobs—and comes little more than a year after another unexpected management reshuffle. While StanChart still does business in 70 countries around the world, the next move could be to sell stakes around Asia, where the bank’s colonial legacy traces the major trade routes of the late 1800s.

HSBC beats a retreat

And HSBC, founded by a Scottish trader in Hong Kong in 1865, said earlier this week that annual profits dropped 17%, thanks to the cost of fines and payouts for numerous misdeeds. Even the bank’s own CEO, Stuart Gulliver, seemed to suggest that the bank was too big to manage, and said HSBC would be trimming assets in Turkey, the US, Brazil, and Mexico.

Gulliver and chairman Douglas Flint gave testimony to an irritable parliamentary committee yesterday, in which Flint said he felt “very ashamed” of the bank’s behavior, most notably—but not exclusively—around allegations that its Swiss unit helped clients evade taxes. The episodes have done “horrible reputational damage” to the bank, he added.

No one is suggesting that these banks will disappear, but they are certainly retrenching aggressively from the historical trade routes that they were built upon. Their American rivals are also facing fines and fees for misdeeds, and struggling to downsize and strengthen their own balance sheets.

That leaves a vacuum in some of the world’s fastest-growing emerging markets, especially in Asia. Who could fill the void? Look to China, home of the world’s largest banks backed by a government eager to cement trade ties—Western banks’ misery is an opportunity for Chinese lenders to begin building their own global empires.