It’s time for America to do away with bail

When it comes to criminal justice, what was radical a half century ago is apparently still radical today. In 1961, my organization, the Vera Institute of Justice, got its start with the Manhattan Bail Project, by testing and proving that most people accused of committing a crime can be safely released from custody and relied on to appear in court—without having to post money bail or to stay in jail until trial.

When it comes to criminal justice, what was radical a half century ago is apparently still radical today. In 1961, my organization, the Vera Institute of Justice, got its start with the Manhattan Bail Project, by testing and proving that most people accused of committing a crime can be safely released from custody and relied on to appear in court—without having to post money bail or to stay in jail until trial.

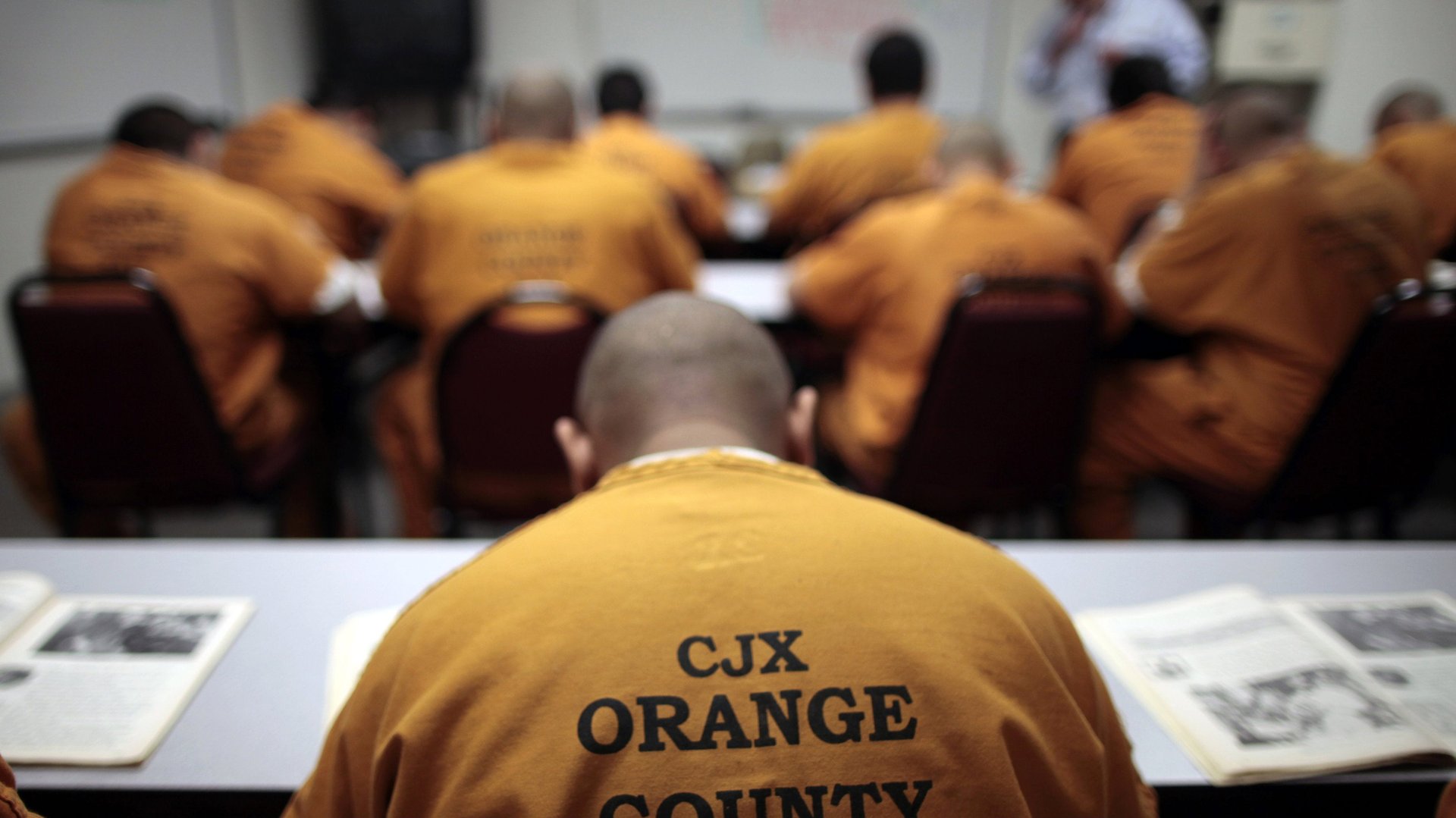

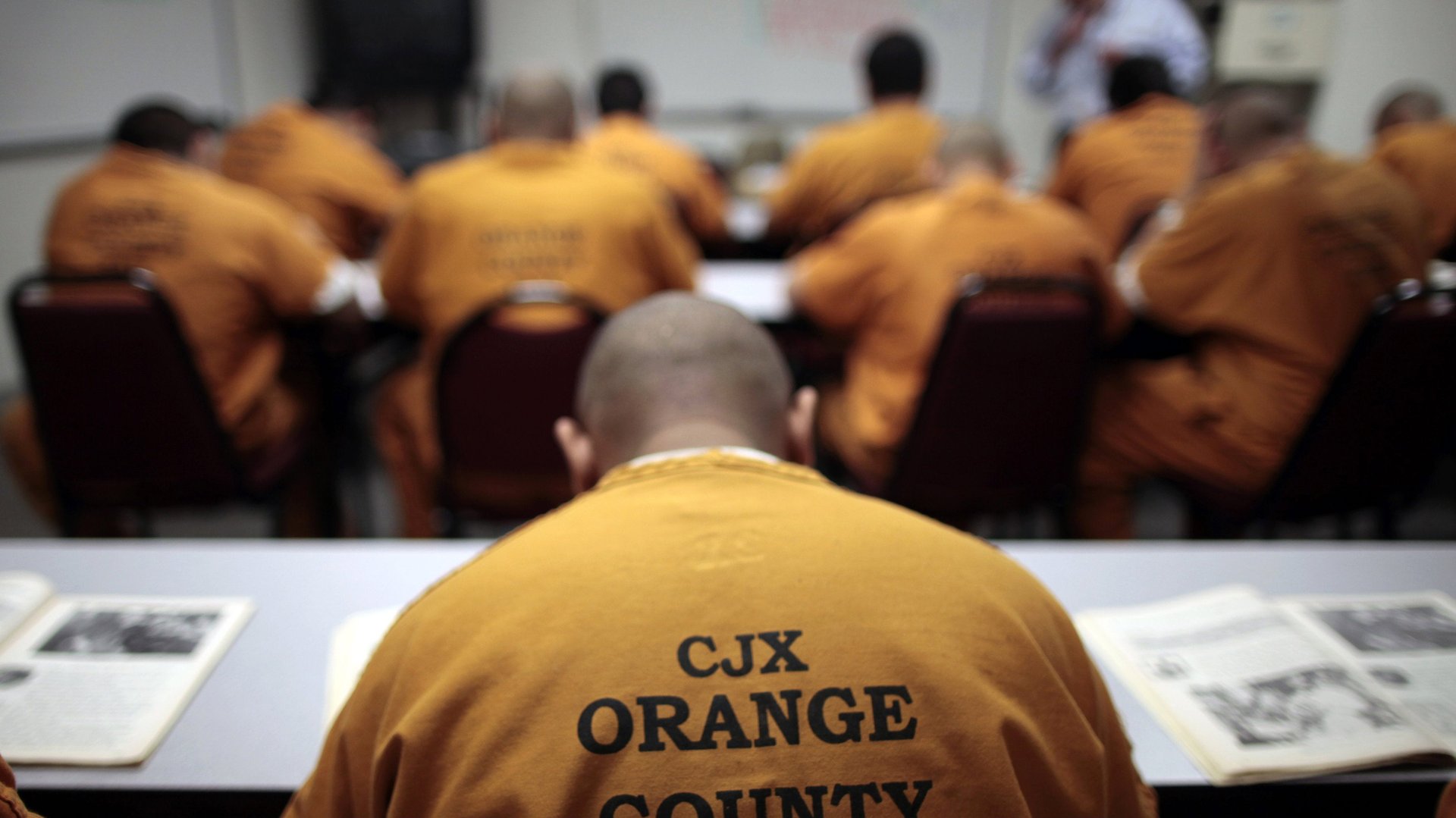

Unfortunately, the lessons we learned and shared in 1961 have not stuck. As a new report from Vera released this month makes clear, jail incarceration remains all too common and, for the most part, unnecessary. On any given day in the United States, there are 731,000 people sitting in more than 3,000 jails. Despite the country growing safer—with violent crime down 49% and property crime down 44% from their highest levels more than 20 years ago—annual admissions to jails nearly doubled between 1983 and 2013, from six million to 11.7 million. This is equivalent to the combined populations of Los Angeles and New York City and nearly 20 times the annual admissions to state and federal prisons.

Although jails serve an important function in local justice systems—to hold people deemed too dangerous to release pending trial or at high risk of flight—this is no longer primarily what jails do or whom they hold. Three out of five people in jail have not been convicted of any crime and are simply too poor to post even low bail to get out while their cases are being processed. Nearly 75% of both pretrial detainees and sentenced offenders are in jail for nonviolent traffic, property, drug, or public order offenses. And underlying the behavior that lands many people in jail in the first place, there is often a history of substance abuse, mental illness, poverty, failure in school, and homelessness. Moreover, jailing practices have had a disproportionate impact on communities of color. Nationally, African Americans are jailed at almost four times the rate of white Americans.

Although most defendants admitted to jail over the course of a year are released within hours or days, rather than weeks or months, even a short stay in jail can have dire consequences. Research has shown that spending as few as two days in jail can increase the likelihood of a sentence of incarceration and the harshness of that sentence, reduce economic viability, promote future criminal behavior, and worsen the health of the largely low-risk defendants who enter them—making jail a gateway to deeper and more lasting involvement in the criminal justice system.

With strong bipartisan support for sentencing reform and re-entry supports for people leaving prison—making strange bedfellows of the likes of the Koch brothers and the ACLU—this is perhaps our once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to effect comprehensive and enduring criminal justice reform. But to be successful, we need start at the beginning, at incarceration’s front door—our local jails.

We can solve hard problems at a local level. Kentucky has a statewide agency that uses a locally validated risk assessment instrument to screen all defendants, which has allowed the courts to release 70%of all defendants pretrial, with only 4%requiring bail. Just 8% of defendants released without bail were rearrested during the pretrial period, and only 10% missed a court date.

In King County, Washington, The Law Enforcement Assisted Diversion program identifies people arrested for low-level drug or prostitution offenses and diverts them away from the criminal justice system and into community-based services. This helps those arrested to make things right and get back on their feet, and reserves expensive criminal justice system resources for more serious cases.

President Obama proposed a critical expansion of pretrial diversion programs in his budget blueprint for fiscal year 2016. The John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation announced last month that it is making an initial $75 million investment in the Safety and Justice Challenge, a multi-year initiative that seeks to address over-incarceration by changing the way Americans think about and use jails. This will support more local innovations—with judges, prosecutors, defense counsel, law enforcement, corrections officers, service providers, and community members working together.

If we are serious about ending over-incarceration, reducing recidivism, improving public safety, and promoting stronger, healthier communities, it is past time to take a hard look at the jails in our cities and counties and begin to chart a different, more sustainable course. To do so, local criminal justice leaders—from police and prosecutors to judges and corrections officials—will have to collaborate and share power with each other—and with defenders, service providers and community members—in ways most have never tried before. But this is critical, necessary work. In a democratic and just society, there should be nothing inevitable or irreversible about the misuse of jails