Lessons for Apple, Instagram, and others from Polaroid’s past and present

The rise and fall and hesitant rise again of Polaroid is both a cautionary tale and an inspiration for businesses. Once a revolutionary think-tank churning out innovations, 30 years after its inception, Polaroid found itself to be a one-product company fighting tooth and nail to preserve its patents.

The rise and fall and hesitant rise again of Polaroid is both a cautionary tale and an inspiration for businesses. Once a revolutionary think-tank churning out innovations, 30 years after its inception, Polaroid found itself to be a one-product company fighting tooth and nail to preserve its patents.

Those patents were the prize possessions of the company’s founder, Edwin Land. Like many cutting-edge companies, Polaroid was headed by a radical leader. Land’s management philosophy led to brilliant brainstorming but not much concern for the bottom line.

Polaroid was founded in 1937, and by 1969, the company had nearly half a billion dollars in annual sales. The company was producing increasingly sophisticated film that developed instantly and attracted artists like Ansel Adams and Chuck Close. Their use helped push sales of the company’s easier-to-use film and cameras to a mass audience.

But Polaroid’s image started to fade in the 1970s, and in the 1980s, Land cut most of his ties with the company. It stumbled often in adapting to the digital age. Polaroid was one of the first companies to develop a digital camera but never brought it to market, fearing it couldn’t profit without selling film.

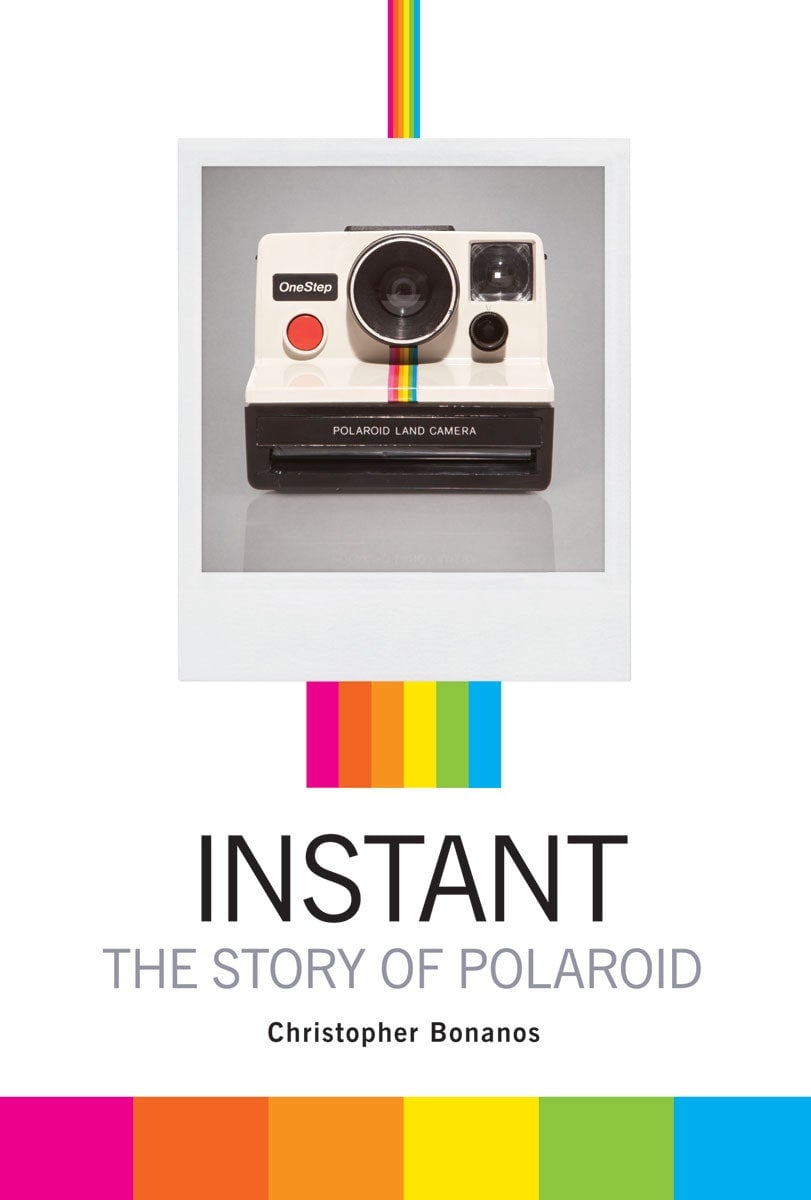

Christopher Bonanos describes the visionary company and its founder with humor and an obvious passion in Instant: The Story of Polaroid. The company, he concludes, laid the blueprint for many startups that came after it, in both positive and negative ways.

“When it introduced instant photography in the late 1940s, Polaroid the corporation followed a path that has since become familiar in Silicon Valley: Tech-genius founder has a fantastic idea and finds like-minded colleagues to develop it; they pull a ridiculous number of all-nighters to do so, with as much passion for the problem-solving as for the product; venture capital and smart marketing follows; everyone gets rich, but not for the sake of getting rich. For a while, the possibilities seem limitless. Then, sometimes, the MBAs come in and mess things up, or the creators find themselves in over their heads as businesspeople, and the story ends with an unpleasant thud.”

History repeats itself.

Apple’s late CEO, Steve Jobs, considered Land a role model, but other companies in the technology, art, and startup worlds can learn from Polaroid’s legacy as well. Quartz interviewed Bonanos on the future of this legendary company and its ongoing influence.

QZ: What is the future of Polaroid?

CB: There does seem to be a hardcore group that is very, very interested in the analog part of the business. It’s a lot smaller than it used to be, but it doesn’t seem to be dying once you get down to the real hardcore enthusiasts; in fact, they seem to be more interested than they used to be a few years ago.

QZ: As Polaroid makes a hesitant comeback, what can other companies learn from the company’s old-fashioned appeal?

CB: When old technologies cease to be mainstream, the technologies often still have niches. I give you the example of vinyl records, which as you know have had a small-scale revival in DJ culture in the past few years. And the reason for that was because they could be cued up by hand. You can’t really do that with a CD—you can’t find a particular spot, you can’t spin it around when you’re listening to headphones and get it in exactly the right spot.

Older technologies, when they go away, people discover that they can’t do certain things with the new one so these niches reveal themselves. And once the business shrinks down to just a niche business, sometimes it will work at a whole new scale.

Polaroid factories were scaled up to make millions upon million of packs of film a year and in some cases they required so much staff and had such big machines that you couldn’t start and stop them easily. They wouldn’t work to make little runs.

QZ: Succession is a fine art, particularly when trying to replace a venerable leader like Land. What made Land’s leaving Polaroid so complicated?

CB: [Relying on powerful company leaders like Land] is a blessing and a curse in some ways. There are some old Polaroid people that have hinted that by the time he left his creativity had maybe been eclipsed by the world. That is, the world had changed and he was still thinking in analog ways. One thing he didn’t do is set up a succession plan that would benefit Polaroid. He was cadged into retirement. He didn’t really want to till he decided to go. He didn’t think much about who would go after him; he said, “well, that’s their problem.” Or something to that effect.

There were people running it after him, but they were not inventors. What I always say when people compare him to Steve Jobs is, in fact, he was Steve Jobs and Steve Wozniak [Apple’s co-founder and chief engineer]. He was the visionary but he also made the thing.

QZ: How can companies avoid being a one-product company as Polaroid was known?

CB: You have to step back from your business and see exactly what you are in the business of doing. The classic example of this is the big railroad companies in the mid-twentieth century, like the Pennsylvania railroad, for example, which was one of the most powerful institutions in America. Now they are not. They moved everything in the first half of the century and in 1950 they might have recognized, “we are not in the business of running trains from city to city, we are in the business of moving people from city to city,” and started an airline. Instead they didn’t; they fought the airlines for market share. And it was obvious to anyone who was going to win that.

Polaroid is the example I always go to. They were in the business of putting images in your hands right away. And they perceived themselves as a maker of film.

(Kodak created an instant camera in the early 1970s to rival Polaroid’s SX-70. In 1976 Polaroid sued Kodak over patent infringement. Fourteen years later Polaroid was awarded nearly a billion dollars. “The only thing that keeps us alive is our brilliance. The only way to protect our brilliance is our patents,” Land once said.)

QZ: How did Polaroid change how patents are used in business?

CB: The feeling was, they did one thing exceptionally well and not that much else at that point. And if they ceded a chunk of it to Kodak, well, Kodak had wider distribution and more marketing power. And if they were both in the same game in the very long term, even if they were in a deal with each other, Polaroid would get hurt.

The feeling at Polaroid was, “if they actually get into this game doing something very much like what we do, they are going to just roll over us.” If Kodak with all of its resources got into this and did something wonderful that really trumped Polaroid, I have the sense that Land would have been impressed and then would strive to beat them. It would have been like two adversaries going at each other to one-up each other. And instead what Kodak came up with was a shabby ripoff, at least that’s how he perceived it. He was offended aesthetically and morally as well as in a legal sense.

There are people who say the case was pursued as vigorously as it was partially out of outrage. And you don’t have to look too far into the Steve Jobs biography by Walter Isaacson to see the same thing. When Samsung started selling a black phone with rows of icons across the front on a touchscreen Jobs said, [paraphrasing,] “We have to defeat this these people—they are just ripping us off.” It was very much the same instinct: “I made something great and you couldn’t beat it so you’re going to copy me?”

One thing that I find very interesting: Polaroid v Kodak was the largest settlement ever paid out until this year. The Apple Samsung award [for patent infringement, granted in August] is $1.05 billion. It’s the first one that’s actually bigger than the Polaroid settlements. All these parallels between Apple and Polaroid and yet another one has asserted itself.

QZ: How does Instagram’s success relate to Polaroid?

CB: Setting aside the filters, most of it is about the sharing specifically: about sharing a stream of snapshots that are causal and constant. There’s a certain kind of picture-taking that you see on Instagram that you would not see on conventional film or even really fancy digital cameras.

You’re documenting yourself and your friends and family as you go about your normal life. This is the way people used SX-70 and Polaroid cameras. It’s not a form of photography that’s entirely new. It was pioneered by Polaroid. Before that people didn’t take pictures quite the same way. Polaroid discovered this sort of casual, vernacular snapshot-taking and encouraged it. Digital technologies because you have instant feedback and because you can share so readily make it almost effortless.

Digital photography may have been the thing that finished off Polaroid’s analog business, but the kind of photography you do on Instagram is Polaroid photography in a different form.

(Below is a mini-film marking the launch of the Polaroid SX-70 that screened during a shareholders’ meeting—an entertaining example of Land’s passion for photography and his aberrant business sense.)

“[The film is] a perfect encapsulation of the Polaroid view of the world. It mixes self-conscious artiness with intense technological talk. It risks going over the heads of viewers, to a degree that an adman would consider insane… It relects Land’s view that if the product was right—not just economically, but also morally and emotionally—the selling would take care of itself… when a shareholder questioned how much he was spending on product development, he was even more dismissive: ‘The bottom line,’ he said, ‘is in heaven.'”