Brewers are desperate to convince Africans to drink more beer

The beer giant SABMiller traces its roots back to Johannesburg in 1895, but even after 120 years the brewer is still trying to crack the African beer market. At a presentation in London, company execs said that the scope for growth on the continent is enormous, provided it can convince the locals to drink more beer.

The beer giant SABMiller traces its roots back to Johannesburg in 1895, but even after 120 years the brewer is still trying to crack the African beer market. At a presentation in London, company execs said that the scope for growth on the continent is enormous, provided it can convince the locals to drink more beer.

SABMiller, the world’s second-biggest brewer and the largest beer seller by volume in 30 of the 38 African markets in which it operates, is targeting 10% annual sales growth on the continent over the next three to five years. That’s roughly double the growth it recorded in Africa last year.

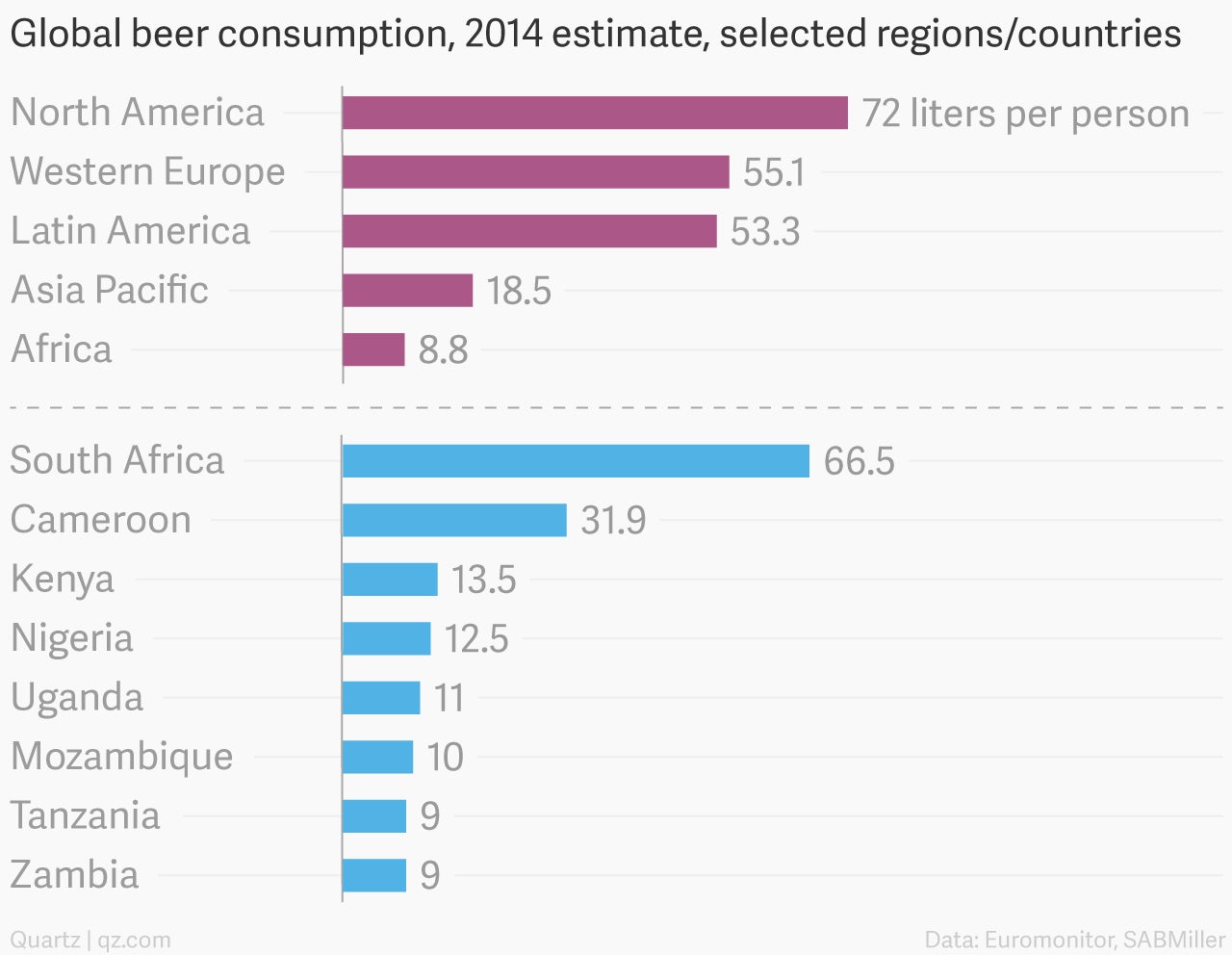

Since 2000, SABMiller says that beer consumption per person has roughly doubled in some countries, such as Mozambique and Uganda, and expanded by 60-70% in Tanzania and Zambia. Still, in these places—and across Africa as a whole—the average person now only consumes around nine liters (16 imperial pints) of beer per year, the brewer says. That’s a fraction of the beer that the typical drinker downs in other regions:

It’s not that Africans necessarily drink less alcohol than their counterparts elsewhere—in terms of pure alcohol consumption, the average African, at just over six liters per year, is right in line with the global average. But the majority of consumption in Africa comes from informal, home-distilled spirits. The challenge for companies like SABMiller is to convince consumers to drink more beer, first of all, and to buy their brew from a formal brand when they do.

The key, SABMiller reckons, will be to keep prices down and do some clever marketing. A shift to “lower pricing regimes,” as the company puts it, will drive greater sales by taking market share from informal and illicit alcohol sellers.

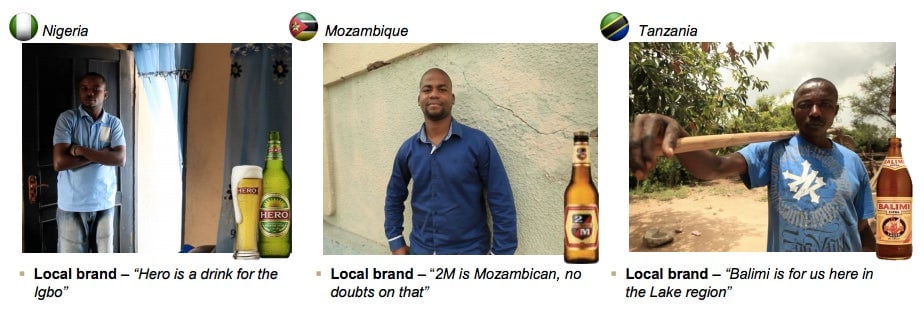

On marketing, instead of focusing on the health risks of home-brewed spirits, SABMiller plans to push beer-drinking as a form of patriotism, touting the local origins and low price points of its African brands. These include Chibuku, brewed from sorghum and corn and packaged in cardboard cartons, and Impala, made from cassava.

In addition to greater affordability, these beers ”tap into local pride,” explained Mark Bowman, SABMiller’s Africa boss, and they present an opportunity to bring consumers into the formal beer market for the first time. It is a message the brewer is hammering home across its African portfolio:

Amin Alkhatib, a drinks analyst at Euromonitor, tells Quartz that Africa will be a “driving force” for sales growth for SABMiller and other global brewers, but it remains a long-term bet rather than a quick money-maker. Profits don’t come easy in Africa, and although SABMiller reckons it can eventually upsell African drinkers to pricier brands, selling more, cheaper beer could dent profitability in the short term.

The brewer plans to defend profits by cutting costs—organizing itself around regional hubs and consolidating its continental supply chain, among other actions. But investors are right to be skeptical, Alkhatib suggests. Even for companies that have been in Africa for more than a century, the region won’t soon shake its reputation as ”the final frontier for the beer market.”