A run-down Welsh city plans to power its homes by harnessing the tides

In the unlovely Welsh city of Swansea, the road from the train station is lined with closed businesses, some with their windows smashed. Swansea Bay, with its vast sandy beach, arcs round to the west, but where the city’s buildings spread down the hills to meet it, they are cut off by a busy road, car parks, and a huge, Brutalist council building.

In the unlovely Welsh city of Swansea, the road from the train station is lined with closed businesses, some with their windows smashed. Swansea Bay, with its vast sandy beach, arcs round to the west, but where the city’s buildings spread down the hills to meet it, they are cut off by a busy road, car parks, and a huge, Brutalist council building.

This south Wales city of 240,000 people, once famous for shipbuilding and metalworking and now fallen into disrepair, is becoming an unlikely trailblazer for a major innovation in alternative energy. Combining huge spring tides and a desperate need for regeneration, Swansea is the site of a new project that could power every house with electricity generated by the ocean’s natural rhythms.

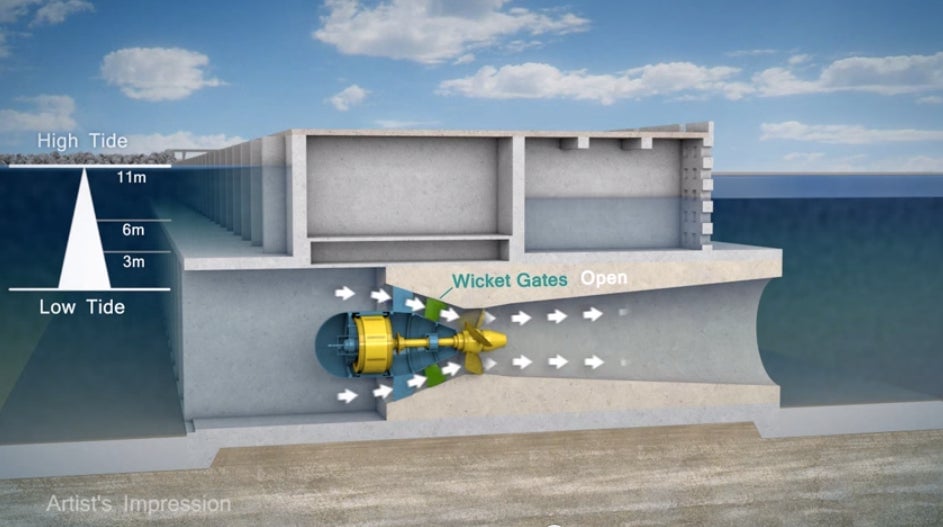

The plan is to construct the first power station in the world based on a man-made tidal lagoon. A seawall of dredged sand, armored with rock, would enclose 11.5 square kilometers of sea. One stretch of wall contains 16 turbines, eight meters in rotor diameter. Gates allowing water to flow through the turbines are opened once a disparity has been achieved between the height of the water inside the lagoon and outside it–or four times a day, once in each direction for high and low tide.

The project could generate enough electricity for 155,000 households, or 90% of the domestic usage of the city, according to Tidal Lagoon Power, the company formed with the aim of bringing this project, and others like it, to fruition.

The power and the pricetag

For a projected cost of over £1 billion ($1.5 billion), this level of power generation is modest. But there are other points in its favor. One is longevity. The lagoon is designed to continue producing electricity at the same rate for 120 years. Another is predictability, because unlike winds which may not blow, or the sun which may not shine, tides always rise and fall at a rate that is knowable ahead of time.

Another reason is more place-specific, but no less pressing: Swansea is crying out (pdf) for something that will draw investment to it. Bomb-damaged in the Second World War and rebuilt in the 1960s, many of the shops in the concrete-dominated central streets of Swansea are boarded up, and the city struggles to attract tourists. Its magnificent beach is divided from its urban heart by bad planning decisions, and despite the golden sand, few enter the water because of sewage outflow into the bay. Within sight along the shore are the chimneys of Port Talbot, still a functioning steelworks.

Swansea’s lagoon has yet to gain the final permissions needed to go into its build phase. But after four-and-a-half years of development, the project has secured £200 million ($300m) in equity funding, and is in the process of raising for another £800 million ($1.2 billion) in debt financing through the infrastructure finance specialists Macquarie.

In October 2014 the insurer Prudential was named (document) as the project’s “cornerstone” investor, and in February the asset manager InfraRed joined them. Neither has formally announced its investment level but each is reported to be in the range of £100 million ($149 million).

While building tidal lagoons for electricity generation is new, large funds buying up infrastructure is not. And in a climate where government bonds are yielding particularly low returns, an asset that promises to pay out over twelve decades might be particularly attractive. To build local support for the project, the company also raised equity from management buy-ins and a local share offer that garnered almost half a million pounds.

Nevertheless, the initial cost of power from the project is higher than any other form of generation, at a projected £168 ($251) per megawatt hour—where energy from fossil fuels typically costs under £100 ($149) and even new offshore wind, the next most expensive form of generation, costs around £140 ($209). Renewable technologies, as well as nuclear and other forms of generation, rely on government subsidies to cushion the risk of building them–costs which find their way to the consumer in higher domestic energy prices.

Tidal Lagoon Power’s Swansea project has been criticized as providing “appalling” value for money by one government-supported non-profit, which called for the plans to be rejected my ministers who have the final say.

And indeed, there’s a big caveat. The developers themselves say that if only one lagoon, at Swansea, is built, the economics don’t make sense. That’s why they want to build five more. The company is proposing lagoons off nearby Cardiff and Newport, which they say could collectively power every home in Wales for over a century, and bring the cost of tidal electricity down to a level comparable with nuclear. Three more lagoons are in the works in Wales, and if all six are built they could generate about 8% of the UK’s electricity.

An ancient method

Tidal power generation does have some precedent, though in slightly different forms. The Sihwa Lake power station in Korea utilizes a seawall built for flood defence to generate power. La Rance in France, which uses a barrage system, rather than a lagoon, has been generating power since 1966.

And the technology’s history goes back much further than that. It has been used to grind corn, says Simon Boxall, a lecturer in oceanography at Southampton University and a specialist in ocean physics. “We’ve been running tide mills in this country for several hundred years, and in some parts of the world for thousands of years,” he says. “They use the same principle as the proposed Swansea Bay tidal lagoon.”

Using the tides for power is a “no-brainer” and an initiative that’s long overdue, he said, because of the predictability that distinguishes tidal power from other renewables, meaning it can be used as baseload—the power a country relies on.

Prospects

Critics have worried that the lagoon’s long walls, sitting proud of the sea’s surface, will spoil the view. Supporters say that far from putting visitors off the bay, it will draw them to it. The company’s projected tourist influx from the project is 100,000 per year.

Plans include a sea walkway, cycle path, electric train line, visitors’ center, and restaurant. Sailing, canoeing, and swimming could take place in the lagoon–after an agreement between the project’s developers and utility Welsh Water that means sewage will no longer flow straight into the bay. An oyster hatchery would help reinstate the decimated oyster population. There are plans for lobster breeding, and the farming of coastline vegetables such as kelp and samphire.

In the center of Swansea a large video used to screen sport and news sometimes plays the Tidal Lagoon Power promotional film about its project, complete with sweeping soundtrack and dazzling computer visualizations—but the film plays to a desolate square in front of a McDonald’s, surrounded by roadworks.

The tidal lagoon represents a utopian vision of green energy for some. For locals, it will also mean 2,000 jobs during construction and 180 in longevity, as well as a reason for more investment finally to settle on Swansea.